I want to go in a different direction and deal with something that bothered me (I don’t know if it bothered anyone else, but this is my class). We talked about Saul and the בעלת אוב, and before about Michal marrying Paltiel and then remarrying David, and David eating the לחם הפנים, and similar cases when the characters in תנ״ך acted in ways that were apparently against the halacha. We brought the explanations of the Rishonim and Acharonim, explaining the details of halacha that justified their actions. This feels funny to me. It seems anachronistic. Do we really think Saul had a copy of the Shulchan Aruch on his desk?

We could answer simply that it’s all the same Torah, that back then they kept the halacha just as we have it today. Understanding the psak halacha tells us what the characters in תנ״ך believed. I would like to take a more sophisticated look at this, one that alleviates my inner anachronism alarm.

We certainly believe they had the Torah in the days of ספר שמואל. They had both the written Torah and the “oral” Torah, the תורה שבעל פה, just as we do today. It’s important to realize that the term תורה שבעל פה has two different meanings.

What do we mean by תורה שבעל פה?

משה קיבל תורה מסיניי, ומסרה ליהושוע, ויהושוע לזקנים, וזקנים לנביאים, ונביאים מסרוה לאנשי כנסת הגדולה.

משה קיבל תורה מסיניי is the first definition of תורה שבעל פה:

כל המצוות שניתנו לו למשה בסיניי—בפירושן ניתנו, שנאמר (שמות כד:יב) ואתנה לך את לוחות האבן, והתורה והמצוה: תורה, זו תורה שבכתב; ומצוה, זה פירושה. וציוונו לעשות התורה, על פי המצוה. ומצוה זו, היא הנקראת תורה שבעל פה.

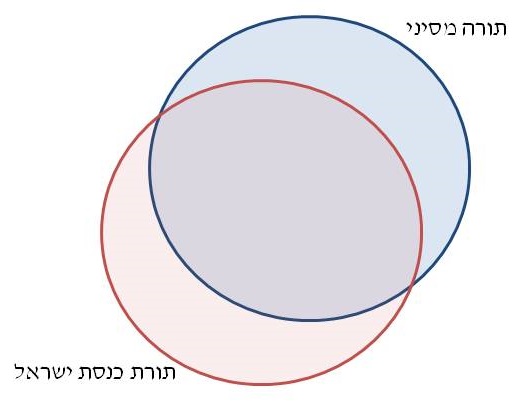

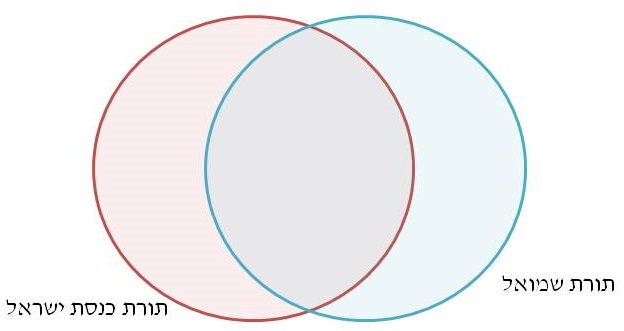

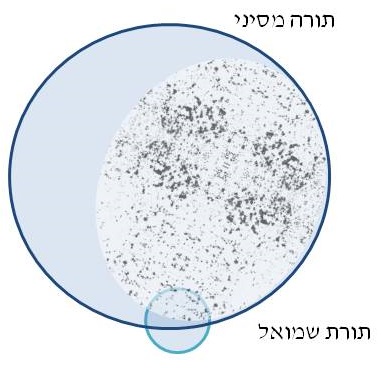

It is the idea that there is an ideal Torah, the sum of all of ה׳‘s will. It is the ideal state of halacha, with no human interpretation or error. This was given to משה (רש״י שמות לא:יח) נמסרה לו תורה במתנה ככלה לחתן, שלא היה יכול ללמוד כולה בזמן מועט כזה. To make this more mathematical, I’m going to intorduce some Venn diagrams. תורה מסיני is the set of all statements that represent ה׳’s will, in a universe of all possible statements:

Rabbi Joel Finkelstein called me a Platonist when I talked about this model, of an ideal heavenly תורה שבעל פה. I don’t really think in Platonic terms about the physical universe, but it’s a useful way to think about the transmission of this תורה שבעל פה, since we human beings are fallible and imperfect:

אמר רב יהודה אמר רב בשעה שנפטר משה רבינו לגן עדן אמר לו ליהושע שאל ממני כל ספיקות שיש לך אמר לו רבי כלום הנחתיך שעה אחת והלכתי למקום אחר לא כך כתבת בי (שמות לג) ומשרתו יהושע בן נון נער לא ימיש מתוך האהל! מיד תשש כחו של יהושע ונשתכחו ממנו שלש מאות הלכות ונולדו לו שבע מאות ספיקות ועמדו כל ישראל להרגו.

But even if some of this Torah is lost, we have ways of recovering it:

במתניתין תנא אלף ושבע מאות קלין וחמורין וגזירות שוות ודקדוקי סופרים נשתכחו בימי אבלו של משה. אמר רבי אבהו אעפ״כ החזירן עתניאל בן קנז מתוך פלפולו.

Zadok HaKohen makes this human side of תורה שבעל פה an important part of his theology:

ותורה שבעל פה היא משחדשו חכמי ישראל וכנסת ישראל על ידי השגת לבם ומוחם מרצון השי״ת, והוא ההשגה שחלק להם השי״ת כפי צמצום לבם ומוחם.

cited in Yaakov Elman, R. Zadok HaKohen on the History of Halakha

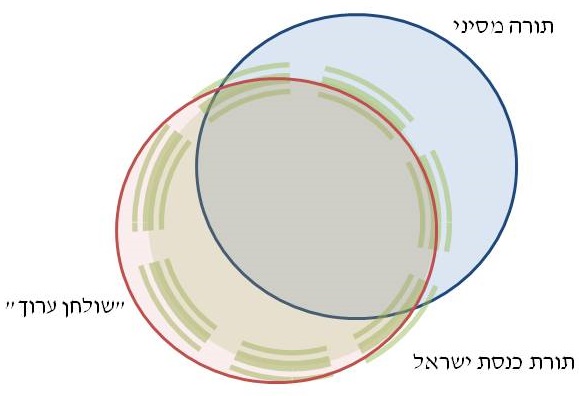

So there are two definitions of תורה שבעל פה, one the ideal received by Moshe, and one the halacha (call it the “Shulchan Aruch”) by which we live our lives. We work under the assumption that they overlap almost completely (i.e. that our behavior corresponds to ה׳'s will) but we have to acknowlege that we may be wrong, that there may be things that we do that we think are right but really should be corrected:

Rav Lichtenstein points out that this model is incomplete:

The halakhic order

comprises three distinct tiers. There is, first, an ideal, and presumably

monistic, plane, the Torah which is ba-shamayyim. It is to this that the

gemara in Bava Metsia alludes when it ascribes to the Ribbono Shel

Olam a position with respect to an issue in taharot. There is, as the final stage, the definitive corpus, the genre

of the Shulhan Arukh, which, having decided among various views,

posits—again, monistically—what is demanded of the Jew. Intermediately, however,

there is the vibrant and entrancing world within which exegetical debate and

analytic controversy are the order of the day, and within which divergent and

even contradictory views are equally accredited. The operative assumption is

that, inherently and immanently, the raw material of Torah is open to diverse

interpretations; that gedolei yisrael, all fully committed and

conscientiously and responsibly applying their talents and their knowledge to

the elucidation of texts and problems, may arrive at different conclusions.

License having been given to them all to engage in the quest, the results all

attain the status of Torah, as a tenable variant reading of devar Hashem:

“Both these and those are words of the living God.”

In reality, our תורה שבעל פה has fuzzy borders and gaps, but for the purpose of this model, we’ll assume there is one, determined halacha (back to figure 2). However, since it is determined by human beings with incomplete memories and imperfect logic, it may change with time. We may reach an understanding that is different from our ancestors.

What does that mean for תנ״ך? The people of the time were people. They behaved according to some rules (this seems incontrovertible); when they were doing the right thing (as indicated by the text), there was some definition of “the right thing”, and when they were wrong, there were some laws or ethical tenets that they were violating. When we read any work of literature, we try to understand the motivation of the characters, but תנ״ך gives us very little of their inner lives. How can we understand the assumptions that underlie their behavior?

From a secular perspective, we could assume that they were the same as us, with our same values, but we would call that projecting and reject such an interpretation. We could look at the archeological evidence and assume the people of ancient Israel shared the values and mores of their neighbors, but we know that’s not true; they dedicated their lives to eliminating the influence of their neighbors. I have a much more powerful tool: I can assume that the rules and tenets that guided their lives were their תורה שבעל פה, which was their best estimation of the heavenly תורה שבעל פה:

Now the key assumption is that both they and we are working from the same ideal:

In studying תנ״ך, we have no way of knowing the will of ה׳. And we also have no way of knowing the standards of the time (their “Shulchan Aruch”). But we do know the Shulchan Aruch that we have. And that is the best available estimate of תורה מסיני, just as תורת כנסת ישראל בזמן שמואל was their best estimate. So I want to know the halacha in a given situation, not to know how I should behave (that’s a subject for a halacha shiur) but as my best estimate for the standards that they were striving for:

And that will be the role of modern halacha in understanding תנ״ך.

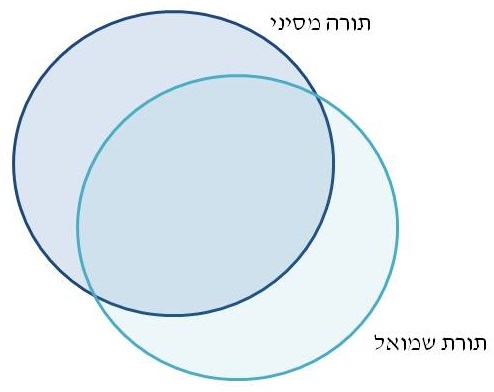

Now there’s one major difference between us (the left-hand set) and the time of שמואל (the right-hand set): שמואל was a נביא. He had a direct line from G-d, a knowlege of absolute Truth.

(דניאל יא:ג)

ועמד מלך גבור; ומשל ממשל רב ועשה כרצונו׃

הוא אלכסנדרוס מקדון שמלך י״ב שנה, עד

כאן היו הנביאים מתנבאים ברוח הקדש; מכאן ואילך (משלי כב:יז) הט אזנך ושמע דברי חכמים.

Does that affect how we see the role of halacha then? Did they have a better, more “accurate” handle on תורה שבעל פה? It’s not so simple:

אמר אמימר: וחכם עדיף מנביא

What does חכם עדיף מנביא mean? There are many explanations, but an important part is that a נביא in fact does not know the תורה שבעל פה simply by being a נביא. This is the concept of לא בשמים היא:

יא כי המצוה הזאת אשר אנכי מצוך היום לא נפלאת הוא ממך ולא רחקה הוא׃

יב לא בשמים הוא; לאמר מי יעלה לנו השמימה ויקחה לנו וישמענו אתה ונעשנה׃

אמר רב יהודה אמר שמואל שלשת אלפים הלכות נשתכחו בימי אבלו של משה אמרו לו ליהושע שאל א״ל (דברים ל) לא בשמים היא

אמרו לו לשמואל שאל אמר להם (ויקרא כז)

אלה המצות

שאין הנביא רשאי לחדש דבר מעתה.

אמר ר׳ יצחק נפחא אף חטאת שמתו בעליה נשתכחה בימי אבלו של משה אמרו לפנחס שאל אמר ליה לא בשמים היא א״ל לאלעזר שאל אמר להם אלה המצות

שאין נביא רשאי לחדש דבר מעתה.

So a נביא cannot tell you the halacha. Note something interesting: we say אין הנביא רשאי לחדש דבר but the “חידוש” that we are talking about is only recalling the תורה שבעל פה that had already been given but had been forgotten. There is only one legitimate way to restore תורה שבעל פה, and that is by human logic:

ודע, שהנבואה לא תועיל בעיון בפירושי התורה ולמידת הדינים בי״ג מדות, אלא מה שיעשה יהושע ופינחס בעניני העיון

והדין הוא מה שיעשה רבינא ורב אשי.

So what does a נביא do? Let’s take a step back to חכם עדיף מנביא:

והוא מן הטעם הזה, שאין כח בנביא, רק שיגיד מה ששמע, לא שיוסיף דבר מלבו. ואם יאמר אמת, מצוה לנו לשמוע לו, ואם יאמר ההפך, מצוה לבלתי שמעו. אך החכם הן שיאמר אמת או לא יאמר, מצוה לשמוע לו.

That’s a very strange statement. How can the Ran say יאמר אמת או לא יאמר, מצוה לשמוע לו?

על פי התורה אשר יורוך ועל המשפט אשר יאמרו לך תעשה לא תסור מן הדבר אשר יגידו לך ימין ושמאל׃

אפילו אומר לך על ימין שהוא שמאל ועל שמאל שהוא ימין…

This always bothered me. How can the Torah tell me that I need to believe something that I unequivocally know to be false? Are we really supposed to suppress our own intellects? The Ramban explains that the opposite is true:

אפילו תחשוב בלבך שהם טועים והדבר פשוט בעיניך כאשר אתה יודע בין ימינך לשמאלך תעשה כמצותם…והצורך במצוה הזאת גדול מאד כי התורה נתנה לנו בכתב וידוע הוא שלא ישתוו הדעות בכל הדברים הנולדים והנה ירבו המחלוקות ותעשה התורה כמה תורות וחתך לנו הכתוב הדין שנשמע לבית דין הגדול העומד לפני השם במקום אשר יבחר…

The halacha אומר לך על ימין שהוא שמאל is procedure, not epistemology. When I listen to a חכם I am not saying that I am wrong; I am entitled to my understanding of the Torah as we quoted Rav Lichtenstein above. I am, however, acknowledging that the חכם's view is legitimate as well. In the ideal state, there is a process for deciding the הלכה למעשה, and we do not want that תעשה התורה כמה תורות. Something has to be decided. But אלו ואלו דברי אלוקים חיים.

שזה נמסר לכל חכם וחכם שיבאר הדבר בדעתו, הן שיאמר אמת או לא יאמרהו, הדבר נמסר לשיקול דעתו, כמו שנהג רבי יהושע עם רבן גמליאל שבא אצלו במקלו ובמעותיו ביום הכיפורים שחל להיות בחשבונו (ר״ה כה א).

Rav Hutner goes further in explaining חכם עדיף מנביא:

ג פעמים שביטולה של תורה זה הוא קיומה שנאמר אשר שברת יישר כוחך ששברת…למדים מכאן חידןש נפלא כי אפשר לה לתורה שתתרבה על ידי שכחת התורה…ופוק חזי מה שאמרו חכמים כי שלש מאות הלכות נשתכחו בימי אבלו של משה והחזירם עתניאל בן קנז בפלפולו. והרי דברי תורה הללו של פלפול החזרת ההלכות, הם הם דברי תורה שנתרבו רק על ידי שכחת התורה. ולא עוד, אלא על פי כן הלא כך אמרו חכמים אף על שהללו מטהרין והללו מטמאין, הללו פוסלין והללו מכשרין…אלו ואלו דברי אלוקים חיים; ונמצא דכל החילוקי דעות וחלופש שיטות הם הגדלת התורה…

ד וחידוש עוד יותר גדול יוצא לנו מכאן כי מרובה היא מדת הבטלת כוחה של תורה שבעל פה המתגלה במחלוקת הדעות, מאשר במקום הסכמת הדעות. כי הלא בהך דאלו ואלו דברי אלוקים חיים כלול הוא היסוד כי גם השיטה הנידחית מהלכה דעת תורה היא…ונמצא כי מחלוקתם של חכמי תורה מגלה את כוחה של תורה שבעל פה הרבה יותר מאשר הסכמתם.מלכמתה של תורה איננה אופן אחד בין האופנים של דברי תורה, אלא שמלכמתה של תורה היא יצירה חיובית של ערכי תורה חדשים, שאין למצוא דגמתם בדברי תורה סתם.

This is not the case with a נביא. To speak in the name of G-d is to be infallible; there is no room for other views. If we disagree with a נביא, we are declaring him a נביא שקר. More than not listening to him, he is liable for capital punishment.

In תנ״ך we see very little of what we would call פסק הלכה. Reb Zadok explains that it is specifically because נבואה was so prevalent that we have so little record of it:

כדתניא הרבה נביאים עמדו להם לישראל כפלים כיוצאי מצרים אלא נבואה שהוצרכה לדורות נכתבה ושלא הוצרכה לא נכתבה.

If אין הנביא רשאי לחדש דבר, then what is the פסק הלכה of a נביא?

וכשתתאמת נבואת הנביא כפי היסודות שביארנו, ונתפרסם כשמואל ואליהו וזולתם, יש לאותו נביא לעשות במצות מעשים שאין שום אדם זולתו רשאי לעשותם…אם צוה לבטל איזו מצוה מכל מצות עשה, או שצוה לעבור על אזהרה מן האזהרות מכל מצות לא תעשה, חייבים לשמוע לו בכל דבריו, וכל העובר על דבריו חייב מיתה בידי שמים, חוץ מע״ז, והוא מאמר חכמים בתלמוד, בכל אם יאמר לך נביא עבור על דברי תורה שמע לו חוץ מע״ז, אבל בתנאי שלא יקבע זה לדורות ויאמר שה׳ צוה בזה לעשות כך וכך לדורות עולם, אלא שיצוה הוראת שעה ובזמן מסויים בלבד.

A נביא has the power of הוראת שעה, of issuing a ruling that is opposed to the “explicit” Torah. He can do this because he represents the word of ה׳ directly and unambiguously. But is limited:

…רוח ה׳ דובר בו בכל מדבר בנבואה ורוח הקודש וממילא הוא מוגדר ומוגבל בפי הכלי והלבוש המגבילו ואין יכולים להשיג רק מה שרצה השם יתברך להראות להם בנבואה. ואף על פי שהיו חכמים גם כן מכל מקום מפאת שפע הנבואה וגילוי שכינה שהיה אז בישראל לא היה נחשב השגה דרך חכמה לכלום כי זה השגה מסופקת…

…בזמן שהיה השראת שכינה בישראל לא היה נכנסים להשגות של מחשכים כלל כי היה אז כל ההנגה על פי נבואה דהיו נביאים כפלים כיוצאי מצרים אלא שנבואה שלא צריכה לדורות לא נכתבה (מגילה יד,א).

אבל כל ההנהגה דלפי שעה היתה על פי נביא…

Anyone who needed a פסק, went to the local נביא. And that נביא decided the halacha, not on the basis of השגה דרך חכמה, since that was נחשב…לכלום, as השגות של מחשכים, as השגה מסופקת; but on the basis of רוח ה׳. But that was by definition הוראת שעה and you couldn’t learn from it:

…לענין אותו דבר הפרטי שנגלה לנביא שהוא ברור ואין בו ספק מה שאין כן כשמשיג בחכמה יכול חכם אחר לחלוק עליו…אבל לענין השגת כלל התורה אצל כלל ישראל חכם עדיף מנביא…שהם מאירים עיני ישראל ומורים להם הדרך בתורת ה׳…שיכול כל אחד להשיג בתורה ולהבין מתוכה בכל פרט מעשה; זהו רק על ידי תורה שבעל פה. דעל ידי נבואה היה צריך בכל פרט לילך אל הרואה והוא היה צריך מראה חדשה באותו פרט.

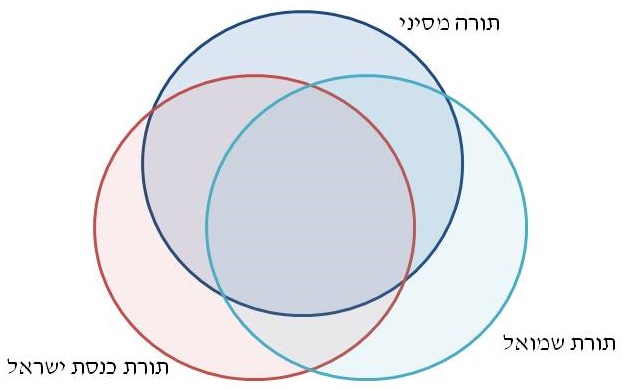

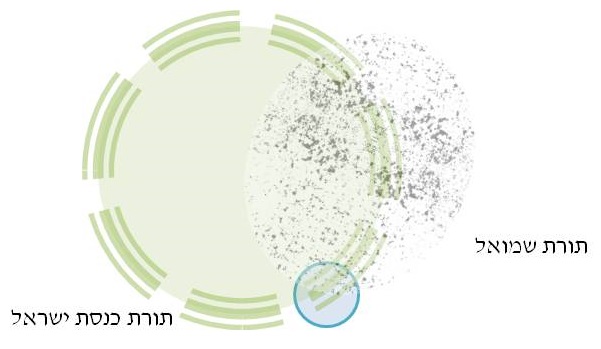

So in our model, תורה שבעל פה in a time of נבואה is in two parts. The smaller part (נחשב…לכלום) was השגה דרך חכמה, just like the entirety of our תורה שבעל פה. The bulk was הנגה על פי נבואה, which was perfect (all inside the תורה מסיני circle) but only individual points. There are no principles, no ways to generalize from a הוראת שעה.

How does this affect our model in learning תנ״ך? If we see a character behaving in a way that goes against halacha, there are four possibilities:

-

The character in תנ״ך is right, and the Shulchan Aruch is wrong. This is theoretically possible (human beings are not perfect), but unknowable. The פוסקי הלכה knew תנ״ך as well as I do, and took the text into account in understanding the הלכה. We have to use our best estimate of the true תורה שבעל פה.

-

The character in תנ״ך is acting against הלכה. Bad guys certainly exist, and we have to rely on our understanding of the text in its context to determine if the נביא (as the divinely-inspired author) approves of the action.

-

The character in תנ״ך is acting against what would be the הלכה, but is acting על פי הוראת שעה of a נביא. Such a situation certainly existed, but שלא הוצרכה [לדורות] לא נכתבה. With ר׳ צדוק, I would assume that a הוראת שעה would not be recorded in the text of נ״ך, so I cannot use this to explain the actions of the characters. This does explain, however, why we do not see them “asking שאלות”; it likely happened but the answers would be הוראת שעה and thus would have no reason to be recorded for posterity.

-

The character in תנ״ך is acting in accordance with the הלכה, but the הלכה or the situation is more nuanced than appears. This is when looking at modern שאלות תשובות helps understand the text itself, and why I can cite modern sources without feeling anachronistic.

Our model is now:

But the only incidents that are written down are the ones in the little blue circle; where they are acting על פי חכם, not על פי נביא.

But there’s a problem with my model of הוראת שעה: there are examples of it recorded in תנ״ך:

ת״ש (דברים יח) אליו תשמעון אפילו אומר לך עבור על אחת מכל מצות שבתורה כגון אליהו בהר הכרמל הכל לפי שעה

ל ויאמר אליהו לכל העם גשו אלי ויגשו כל העם אליו; וירפא את מזבח ה׳ ההרוס׃

לא ויקח אליהו שתים עשרה אבנים כמספר שבטי בני יעקב אשר היה דבר ה׳ אליו לאמר ישראל יהיה שמך׃

לב ויבנה את האבנים מזבח בשם ה׳; ויעש תעלה כבית סאתים זרע סביב למזבח׃

לג ויערך את העצים; וינתח את הפר וישם על העצים׃

…

לח ותפל אש ה׳ ותאכל את העלה ואת העצים ואת האבנים ואת העפר; ואת המים אשר בתעלה לחכה׃

לט וירא כל העם ויפלו על פניהם; ויאמרו ה׳ הוא האלקים ה׳ הוא האלקים׃

The problem is that במות, private altars, are forbidden when there is a central משכן or בית מקדש. So this is a classic הוראת שעה: אליהו's מזבח is forbidden, but he is a נביא and can tell the people that now, at this time only, they are to build it. Similarly גדעון and מנוח are told to offer sacrifices in their own homes.

But the common theme of all these הוראות שעה in תנ״ך is that they are all about the centralization of the עבודה, and that has its own halacha:

י ועברתם את הירדן וישבתם בארץ אשר ה׳ אלקיכם מנחיל אתכם; והניח לכם מכל איביכם מסביב וישבתם בטח׃ יא והיה המקום אשר יבחר ה׳ אלקיכם בו לשכן שמו שם שמה תביאו את כל אשר אנכי מצוה אתכם; עולתיכם וזבחיכם מעשרתיכם ותרמת ידכם וכל מבחר נדריכם אשר תדרו לה׳׃

יב ושמחתם לפני ה׳ אלקיכם אתם ובניכם ובנתיכם ועבדיכם ואמהתיכם; והלוי אשר בשעריכם כי אין לו חלק ונחלה אתכם׃ יג השמר לך פן תעלה עלתיך בכל מקום אשר תראה׃ יד כי אם במקום אשר יבחר ה׳ באחד שבטיך שם תעלה עלתיך; ושם תעשה כל אשר אנכי מצוך׃

אשר יעלה בלבך, אבל אתה מקריב על פי נביא, כגון אליהו בהר הכרמל.

So this whole category of halacha, the המקום אשר יבחר ה׳, is different. It requires the involvement of the נביא, and the violations of that rule are less an example of הוראת שעה per se, but an explicit exception in the איסור of במות. The halacha of הוראת שעה doesn’t need examples in תנ״ך; it comes explicitly from the Torah: אליו תשמעון. But it is a הבואה שלא הוצרכה לדורות, one that cannot be used to understand and extend תורה שבעל פה, so it will not be recorded. A הוראת שעה within the laws of המקום אשר יבחר ה׳, however, is הוצרכה לדורות; it is part and parcel of the תורה שבעל פה.

We see these played out most explicitly when David wants to build the בית מקדש:

א ויהי כי ישב המלך בביתו; וה׳ הניח לו מסביב מכל איביו׃

ב ויאמר המלך אל נתן הנביא ראה נא אנכי יושב בבית ארזים; וארון האלהים ישב בתוך היריעה׃

ג ויאמר נתן אל המלך כל אשר בלבבך לך עשה; כי ה׳ עמך׃

ד ויהי בלילה ההוא;

ויהי דבר ה׳ אל נתן לאמר׃

ה לך ואמרת אל עבדי אל דוד

כה אמר ה׳; האתה תבנה לי בית לשבתי׃

ו כי לא ישבתי בבית למיום העלתי את בני ישראל ממצרים ועד היום הזה; ואהיה מתהלך באהל ובמשכן׃

…יב כי ימלאו ימיך ושכבת את אבתיך והקימתי את זרעך אחריך אשר יצא ממעיך; והכינתי את ממלכתו׃

יג הוא יבנה בית לשמי; וכננתי את כסא ממלכתו עד עולם׃

…יז ככל הדברים האלה וככל החזיון הזה כן דבר נתן אל דוד׃

What is going on here? We will deal with the reason that ה׳ does not let David build the בית מקדש when we get to this chapter, but Rabbi Leibtag points out something interesting. David first goes to נתן to ask a פסק as a חכם: he is “darshening out the pasuk”. The Torah says הניח לכם מכל איביכם מסביב, and David sees his situation as ה׳ הניח לו מסביב מכל איביו, so it’s obviously time (David of course did not read the words of the תנ״ך; the author here is pointing out what the situation was). And נתן, wearing his “Rabbi” hat, agrees: it it time to build the בית מקדש. Then comes the נבואה, and the הוראת שעה: no, David cannot. And this outweighs the פסק. But there’s no reason, no way to generalize a rule about when הניח מסביב applies.

So this is my approach to understanding the halacha in תנ״ך: if the characters are portrayed in a positive light, I assume they are acting consistently with the halacha as we understand it today. If a נביא acting as a נביא gives an instruction related to the בית מקדש (including issues of מלכות) it is a הוראת שעה and cannot be related to a halachic decision. And then we wait for Eliyahu Hanavi, תשבי יתרץ קושיות ובעיות.