We’ve looked at David’s final instructions to Shlomo:

א ויקרבו ימי דוד למות; ויצו את שלמה בנו לאמר׃ ב אנכי הלך בדרך כל הארץ; וחזקת והיית לאיש׃

But what is involved in היית לאיש? What would David say is the right way for a person to live? What is the good life?

Mongol General: Conan, what is best in life?

Conan: To crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women.

But we are not Conan. For us, being a mensch means something different. There are three פרקי תהילים that I think represent the Psalmist’s answer to that question.

א מזמור לדוד; ה׳ מי יגור באהלך; מי ישכן בהר קדשך׃ ב הולך תמים ופעל צדק; ודבר אמת בלבבו׃ ג לא רגל על לשנו לא עשה לרעהו רעה; וחרפה לא נשא על קרבו׃ ד נבזה בעיניו נמאס ואת יראי ה׳ יכבד; נשבע להרע ולא ימר׃ ה כספו לא נתן בנשך ושחד על נקי לא לקח; עשה אלה לא ימוט לעולם׃

The question of מי יגור באהלך is very similar to the question in the שיר של יום ליום ראשון, which we are all familiar with:

ג מי יעלה בהר ה׳; ומי יקום במקום קדשו׃ ד נקי כפים ובר לבב; אשר לא נשא לשוא נפשי; ולא נשבע למרמה׃

But that is an abbreviated version of our perek. The gemara sees our perek as David’s summary of all the mitzvot:

בא דוד והעמידן [תרי״ג מצוות] על אחת עשרה דכתיב (תהלים טו:א) ”מזמור לדוד ה׳ מי יגור באהלך מי ישכון בהר קדשך הולך תמים…“

It’s notable that these eleven principles are mostly בין אדם לחברו. These are the things that are “best in life”, not to crush our enemies but to elevate them.

The gemara goes on to give examples of each:

הולך תמים: זה אברהם דכתיב (בראשית יז:א) הִתְהַלֵּךְ לְפָנַי וֶהְיֵה תָמִים.

הולך תמים means to have the serenity to accept whatever happens.

תמים תהיה עם ה׳ אלקיך: התהלך עמו בתמימות, ותצפה לו, ולא תחקר אחר העתידות, אלא כל מה שיבא עליך קבל בתמימות ואז תהיה עמו ולחלקו.

פועל צדק: כגון אבא חלקיהו.

פועל צדק doesn’t mean “to act with justice”, but “to be a just, honest, worker”.

אבא חלקיה בר בריה דחוני המעגל הוה, וכי מצטריך עלמא למיטרא הוו משדרי רבנן לגביה ובעי רחמי…אזול בדברא ואשכחוה דהוה קא רפיק, יהבו ליה שלמא ולא אסבר להו אפיה…אמרו ליה: ידעינן דמיטרא מחמת מר הוא דאתא, אלא לימא לן מר הני מילי דתמיהא לן: מאי טעמא כי יהיבנא למר שלמא לא אסבר לן מר אפיה? אמר להו: שכיר יום הואי, ואמינא: לא איפגר.

ודובר אמת בלבבו: כגון רב ספרא.

We use the expression דובר אמת בלבבו in davening:

לְעוֹלָם יְהֵא אָדָם יְרֵא שָׁמַֽיִם בְּסֵֽתֶר וּבַגָּלוּי וּמוֹדֶה עַל הָאֱמֶת וְדוֹבֵר אֱמֶת בִּלְבָבוֹ וְיַשְׁכֵּם וְיֹאמַר:

רִבּוֹן כָּל הָעוֹלָמִים לֹא עַל צִדְקוֹתֵֽינוּ אֲנַֽחְנוּ מַפִּילִים תַּחֲנוּנֵֽינוּ לְפָנֶֽיךָ כִּי עַל רַחֲמֶֽיךָ הָרַבִּים

which has the sense of “don’t be a hypocrite with G-d”. But the gemara says it means “don’t be a hypocrite with people”.

רב ספרא: בשאלתות דרב אחא (שאילתא לו): והכי הוה עובדא דרב ספרא. היה לו חפץ אחד למכור, ובא אדם אחד לפניו בשעה שהיה קורא ק״ש, ואמר לו תן לי החפץ בכך וכך דמים, ולא ענהו מפני שהיה קורא ק״ש. כסבור זה שלא היה רוצה ליתנו בדמים הללו, והוסיף. אמר תנהו לי בכך יותר .לאחר שסיים ק״ש, אמר לו: טול החפץ בדמים שאמרת בראשונה, שבאותן דמים היה דעתי ליתנם לך.

לא רגל על לשונו: אנקוש״א [encusa] בלעז כמו (שמואל ב יט:כח) וַיְרַגֵּל בְּעַבְדְּךָ. מזמור זה להודיע מדת חסידות.

That is פשט. Don’t say לשון הרע. We have seen so many פרקי תהילים focusing on the evils of לשון הרע.

לא עשה לרעהו רעה: שלא ירד לאומנות חבירו.

עשה לרעהו רעה refers specifically to unfair competition. Honesty in business is more than being honest with customers and suppliers; it means being honest with competitors.

וחרפה לא נשא על קרובו: זה המקרב את קרוביו.

Kindness is no less a mitzvah, no less powerful when done for members of our immediate family. In fact the opposite is true.

Our family is our first responsibility. They are the most dependent on our chesed. Giving to them should be our greatest pleasure.

It doesn’t get us honored at banquets. We may not experience the same show of gratitude. But we certainly reap the rewards.

נבזה בעיניו נמאס: וספר ממדותיו הטובות עוד: כי אף על פי שהוא הלך תמים ופעל צדק ודבר אמת אינו מתגאה בזה, אלא נבזה הוא בעיניו ונמאס, וחושב בלבבו כי לא יעשה אחת מני אלף ממה שיש עליו חובה לעשות לכבוד הבורא.

ואת יראי ה׳ יכבד:…והטובות שיעשה זולתו יחשבן לדברים גדולים. ויחשוב שיש ליראי ה׳ זולתו מעלה עליו, ושהם יראים השם יותר ממנו ונותן להם מעלה עליו ומכבד אותם.

These two are about modesty. Virtue signaling is no virtue.

[נשבע להרע] ולא ימר: מה שנשבע אף על פי שמריע לגופו. ולא ימר, אלא יקים כמו שאמר.

This is the one that is mentioned in פרק כד.

נקי כפים ובר לבב; אשר לא נשא לשוא נפשי; ולא נשבע למרמה

Keep your word, even if you will have to pay a price for it.

כספו לא נתן בנשך: אפילו ברבית עובד כוכבים.

This פרק isn’t about explicit sins. We know that we shouldn’t take interest. David is adding here that interest is problematic even when it is legal.

והתורה לא אסרה אלא לישראל, אבל לנכרי מותר כמו שנאמר (דברים כג:כא): לַנׇּכְרִי תַשִּׁיךְ. ולא נאמר כן בגזלה וגנבה ובאבדה ובהונאה, כי אפילו לנכרי אסור להונותו או לגזלו או לגנוב ממונו; אבל הנשך שהוא לוקח ממנו ברצונו ובדעתו מותר.

מלוה בריבית: אחד המלוה ואחד הלוה. ואימתי חזרתן? משיקרעו את שטריהן, ויחזרו בהן חזרה גמורה, אפילו לנכרי לא מוזפי.

דאפילו לנכרי: שישתכח שם ריבית מפיהם; דתו ודאי לא הדרי לקלקולייהו.

The psalmist sees ריבית, interest, as a moral failing rather a financial tort. The halacha clearly thinks that it is, because it is forbidden even if both parties agree, and both parties are liable for violating it. I can agree to overpay for an item, but I cannot agree to overpay for a loan.

מדוע קיים איסור ריבית דווקא בהלוואה? הרי, במקרה שאדם מוכר חפץ מסוים לאדם אחר, מותר לו להעלות את המחיר ולהרוויח מן המכירה (בכפוף להסכמת הקונה). מדוע, בניגוד לשאר התחומים הממוניים, אסור לאדם שמלווה כסף להרוויח מהלוואתו?

The problem is that it represents a dangerous attitude about money. Money should be a tool for accomplishing goals, not a goal into itself. Paying for things is how the world works; paying for money means I’m interested in some number that makes me better than others. I think Aristotle said it best:

[U]sury is most reasonably hated, because its gain comes from money itself and not from that for the sake of which money was invented. For money was brought into existence for the purpose of exchange, but interest increases the amount of the money itself…consequently this form of the business of getting wealth is of all forms the most contrary to nature.

אם כסף תלוה את עמי [את העני עמך]: פירוש אם ראית שהיה לך כסף יתר על מה שאתה צריך לעצמך, שאתה מלוה לעמי, תדע לך שאין זה חלק המגיעך אלא חלק אחרים שהוא ”העני עמך“, ובזה רמז כי צריך לפתוח לו משלו.

ושוחד על נקי לא לקח: כגון ר׳ ישמעאל בר׳ יוסי.

רבי ישמעאל ברבי יוסי, הוה רגיל אריסיה דהוה מייתי ליה כל מעלי שבתא כנתא דפירי. יומא חד אייתי ליה בחמשה בשבתא. אמר ליה: מאי שנא האידנא? אמר ליה: דינא אית לי, ואמינא, אגב אורחי אייתי ליה למר. לא קביל מיניה. אמר ליה: פסילנא לך לדינא.

These are all about our relationship with other people, treating other people with respect.

[A]ll ethics derive from a confrontation with an other. This other, with whom we interact concretely, represents a gateway into the more abstract Otherness.

The distinction between totality and infinity divides the limited world, which contains the other as a material body, from a spiritual world. Subjects gain access to this spiritual world, infinity, by opening themselves to the Otherness of the other.

Since the perek sets a standard that is far too high for any human being to reach, the gemara reassures us that achieving any of these is a good thing:

כתיב ”עושה אלה לא ימוט לעולם“. כשהיה ר״ג מגיע למקרא הזה היה בוכה; אמר: מאן דעביד להו לכולהו הוא דלא ימוט הא חדא מינייהו ימוט! אמרו ליה: מי כתיב ”עושה כל אלה“; ”עושה אלה“ כתיב; אפילו בחדא מינייהו.

There is another perek with a very similar theme.

א לדוד מזמור; חסד ומשפט אשירה; לך ה׳ אזמרה׃ ב אשכילה בדרך תמים מתי תבוא אלי; אתהלך בתם לבבי בקרב ביתי׃ ג לא אשית לנגד עיני דבר בליעל; עשה סטים שנאתי; לא ידבק בי׃ ד לבב עקש יסור ממני; רע לא אדע׃

אתהלך בתם לבבי is the הולך תמים of the perek above. But here David is talking about himself, not the abstract “מי ישכן בהר קדשך”. And he is talking about his everyday existence, in his own home: בקרב ביתי. The way to achieve this דרך תמים is to remove all the distractions that are keeping me from reaching my potential.

מתי תבא אלי: הטעם: כי הוא ישכיל תמיד בכל רגע להרגיל עצמו ללכת בה, עד שלא ייגע ללכת, וכאילו הדרך תבא אליו מאליה, כדרך הכינור מרוב הרגילות…ידבר על עת התבודדו והבדלו.

ורבי משה אמר: שתשרה הרוח הקדש עליו בביתו בהתבודדו מבני אדם, ודיניהם וריבם.

He wants simply to practice being good, but that’s hard when he has to deal with real-world politics.

כי אתהלך בתם לבבי כו׳: והוא כי אפנה לבי מכל מחשבות והרהורים והקפדות גם כי יצרו אותי בני אדם או יסורין יבאו אלי השתי יצרים הנכללים באמור לבבי יחד שמהם יהיו הולכים ומתנהגים.

בכל לבבך: בשני יצריך, ביצר טוב וביצר הרע.

עֲשֹׂה־סֵטִים means “being distracted”. David says he hates that.

סטים: ענינו דברים הסרים מדרך הנכוחה כמו (משלי ז:כה) אַל יֵשְׂטְ אֶל דְּרָכֶיהָ. .

This is something only possible after his retirement. As king, there is not getting away from בני אדם, ודיניהם וריבם.

The perek then repeats the theme of פרק טו but in the negative: these are the people who I don’t want in my house. It has a chiastic structure, centered around the same הלך בדרך תמים.

ה מלושני (מלשני) בסתר רעהו אותו אצמית;

גבה עינים ורחב לבב אתו לא אוכל׃

ו עיני בנאמני ארץ לשבת עמדי;

הלך בדרך תמים הוא ישרתני׃

ז לא ישב בקרב ביתי עשה רמיה;

דבר שקרים לא יכון לנגד עיני׃

ח לבקרים אצמית כל רשעי ארץ;

להכרית מעיר ה׳ כל פעלי און׃

אצמית is usually translated “cut off” (Koren) or “destroy” (JPS) but the Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon connects it to the Arabic “صَمَتَ”, samat, “silence”. I think that fits the context here better, because I think this description of מלשני בסתר רעהו and the sinners is metaphoric. David is looking at himself and trying to suppress his own יצר הרע to לשון הרע and שקר, because he wants to end up in a state of (תהלים כז:ד) שִׁבְתִּי בְּבֵית ה׳ כָּל יְמֵי חַיַּי.

מר רב חסדא ואיתימא מר עוקבא: כל אדם שיש בו גסות הרוח, אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: אין אני והוא יכולין לדור בעולם. שנאמר: ”מלשני בסתר רעהו אותו אצמית; גבה עינים ורחב לבב אתו לא אוכל“ אל תקרי אֹתוֹ אלא אִתּוֹ לא אוכל.

So he will silence the source of evil לבקרים, which means “every morning”, in the sense that every day is a new start.

כב חסדי ה׳ כי לא תמנו כי לא כלו רחמיו׃ כג חדשים לבקרים רבה אמונתך׃

יז מה אנוש כי תגדלנו; וכי תשית אליו לבך׃ יח ותפקדנו לבקרים; לרגעים תבחננו׃

Every morning is a chance to get things right or to mess them up again. This perek is David’s version of Groundhog Day.

The conclusion, the goal of David’s התבודדו והבדלו is the final half-verse: להכרית מעיר ה׳ כל פעלי און. That is what is “best in life”.

תנא דבי רבי אלעזר בן יעקב: כל מקום שנאמר ”נצח“ ”סלה“ ”ועד“, אין לו הפסק עולמית; ”נצח“, דכתיב (ישעיהו נז:טז) כִּי לֹא לְעוֹלָם אָרִיב וְלֹא לָנֶצַח אֶקְּצוֹף.

הנה אמרו רז״ל פה אחד הסכימו כי מזמור זה על אדם הראשון ידבר.

(בראשית ה:א) זה ספר תולדות אדם: העביר לפניו כל הדורות. הראהו דוד חיים חקוקין לו ג׳ שעות. אמר לפניו: רבונו של עולם, לא תהא תקנה לזה? אמר: כך עלתה במחשבה לפני. א״ל: כמה שני חיי? א״ל: אלף שנים. א״ל: יש מתנה ברקיע? א״ל: הן. א״ל: ע׳ שנים משנותי יהיו למזל זה.

Metaphorically, David is a little piece of אדם הראשון, living a normal life ((תהלים צ:י) יְמֵי שְׁנוֹתֵינוּ בָהֶם שִׁבְעִים שָׁנָה). He is everyman, and תהילים is meant to be the story of everyone. This perek is a נצח about the purpose of human existence.

א למנצח לדוד מזמור; ה׳ חקרתני ותדע׃ ב אתה ידעת שבתי וקומי; בנתה לרעי מרחוק׃

לרעי. לרעיוני, כמו (פסוק יז) וְלִי מַה יָּקְרוּ רֵעֶיךָ אֵ־ל.

ארחי ורבעי זרית; וכל דרכי הסכנתה׃

ארחי ורבעי: דרכי ורבצי סבבת וגדרת להם חוק וגבול ולא יעבור.

מצודת דוד, תהילים קלט:ג

This is more than ה׳ watching; זרית means “you encircled me”; (שמות כה:יא) ועשית עליו זר זהב סביב. Your knowledge of me limits me. We know this as a philosophical problem:

הכל צפוי, והרשות נתונה, ובטוב העולם נדון. והכל לפי רוב המעשה.

But the message here is not about predestination and free will, but the fact that I cannot hide from You and that awareness keeps me in control.

ד כי אין מלה בלשוני; הן ה׳ ידעת כלה׃ ה אחור וקדם צרתני; ותשת עלי כפכה׃ ו פליאה דעת ממני; נשגבה לא אוכל לה׃

אחור וקדם, ”future and past“ means that ה׳ is omniscient in time as well as space. Now David is talking does realize that this limits his free will (תשת עלי כפכה) but that is a dialectic that he will never understand; פליאה דעת ממני. But I can’t escape it.

ז אנה אלך מרוחך; ואנה מפניך אברח׃ ח אם אסק שמים שם אתה; ואציעה שאול הנך׃ ט אשא כנפי שחר; אשכנה באחרית ים׃ י גם שם ידך תנחני; ותאחזני ימינך׃ יא ואמר אך חשך ישופני; ולילה אור בעדני׃ יב גם חשך לא יחשיך ממך; ולילה כיום יאיר כחשיכה כאורה׃

But what that all leads to is that I cannot escape the consequences of my own actions. אשא כנפי שחר; אשכנה באחרית ים refers to the furthest east and west. ולילה אור בעדני means “the night will provide me with darkness”; in an unfortunate irony, אור in Aramaic means “night”.

ולילה אור בעדני: והלילה יהי מאפיל לנגדי, אור זה לשון אופל הוא כמו (איוב לז:יא) יָפִיץ עֲנַן אוֹרוֹ, וכן (תהילים קמח:) כָּל כּוֹכְבֵי אוֹר, וכן (שמות יד:) וַיָּאֶר אֶת הַלָּיְלָה.

This has halachic implications.

מתניתן: אור לארבעה עשר בודקין את החמץ…

גמרא: מאי ”אור“? רב הונא אמר: נגהי, ורב יהודה אמר: לילי.

Then we have the volta: from ה׳'s omniscience about my deepest thoughts to the fact that I cannot begrudge You that; You made me.

יג כי אתה קנית כליתי; תסכני בבטן אמי׃ יד אודך על כי נוראות נפליתי; נפלאים מעשיך; ונפשי ידעת מאד׃ טו לא נכחד עצמי ממך; אשר עשיתי בסתר; רקמתי בתחתיות ארץ׃ טז גלמי ראו עיניך ועל ספרך כלם יכתבו; ימים יצרו; ולא (ולו) אחד בהם׃

גלמי means literally, “my golem”, my inert body before I was born. David then gets back to the predestination/free will dialectic:

ימים יצרו ולא אחד בהם: כל מעשה האדם ותכליתיהם גלוים לפניך כאילו יוצרו כבר, אע״פ שלא היה אחד מכולם ולא היה עדיין כאחד בעולם. ואלו הם פלאי מפעלות אלקים ומשפט גבורתו שעתידות גלוים לפניו טרם תבאנה.

The כתיב-קרי of ולא-ולו we’ve seen before:

דעו כי ה׳ הוא אלקים; הוא עשנו ולא (ולו) אנחנו עמו וצאן מרעיתו׃

And here it has a similar double meaning: Rashi’s “You know me as though you already created the days of my life, even though they don’t exist yet” and “You created the days of my life and You own every one of them”.

יז ולי מה יקרו רעיך א־ל; מה עצמו ראשיהם׃ יח אספרם מחול ירבון; הקיצתי ועודי עמך׃

The perek started with בנתה לרעי, ”You know my thoughts“, and ends with ולי מה יקרו רעיך: ”Your thoughts are too deep for me“.

Then David turns to a prayer: You know everything. Punish sinners; I may be aware of their evil but I cannot do anything to them. That is on you.

יט אם תקטל אלו־ה רשע; ואנשי דמים סורו מני׃ כ אשר ימרוך למזמה; נשוא לשוא עריך׃ כא הלוא משנאיך ה׳ אשנא; ובתקוממיך אתקוטט׃ כב תכלית שנאה שנאתים; לאויבים היו לי׃

ימרוך למזמה: מזכירים שמך על כל מחשבות רעתם ומכנים אלקותך לע״ג.

נשוא לשוא: כמו נשאו לשוא.

עריך: אויביך, נשאו לשוא אויביך את שמך.

And the perek ends with a prayer that echoes the beginning: it started with ה׳ חקרתני and now,

כג חקרני א־ל ודע לבבי; בחנני ודע שרעפי׃ כד וראה אם דרך עצב בי; ונחני בדרך עולם׃

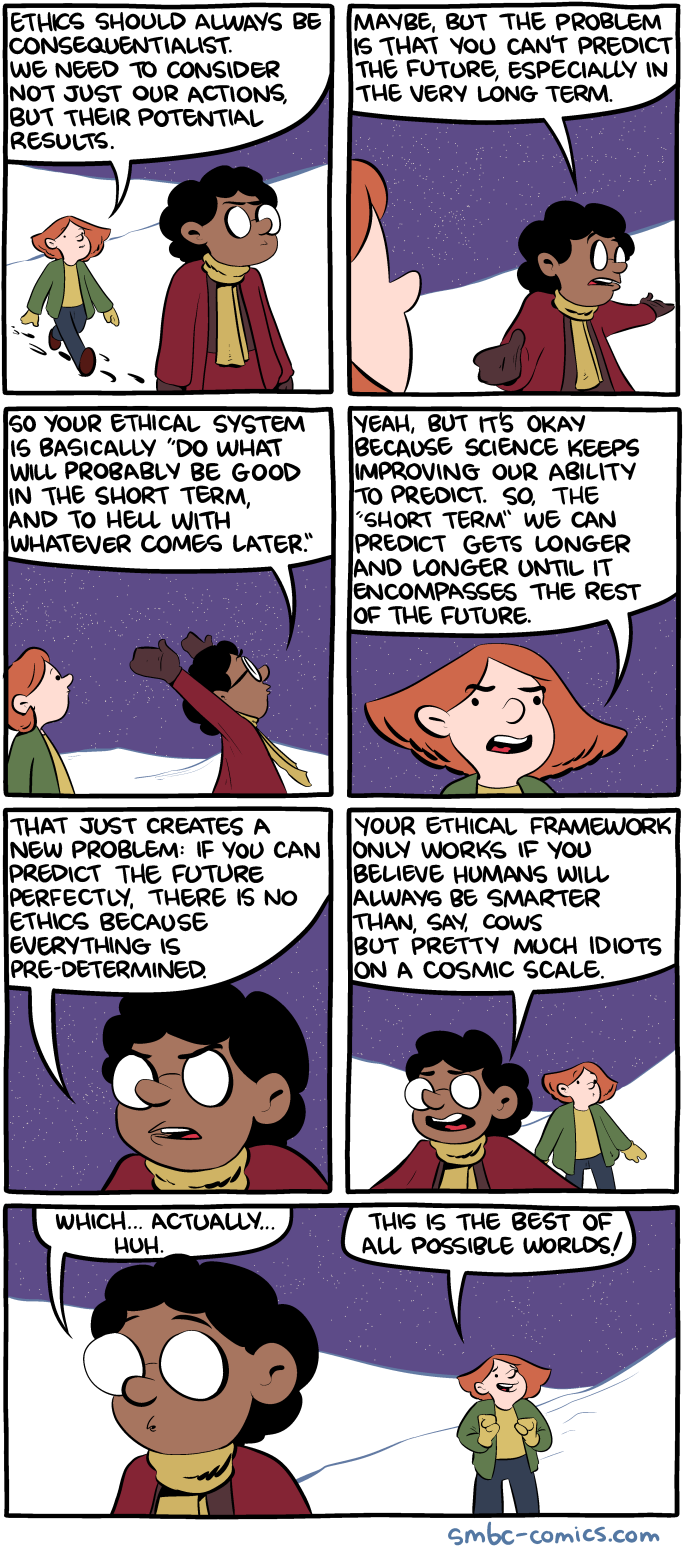

I do my best, but I can’t predict the future. Only you know אם דרך עצב בי. Help me make the right choices, because human ethics is by definition impossible.