צז מה אהבתי תורתך; כל היום היא שיחתי׃

צח מאיבי תחכמני מצותך; כי לעולם היא לי׃

צט מכל מלמדי השכלתי; כי עדותיך שיחה לי׃

ק מזקנים אתבונן; כי פקודיך נצרתי׃

קא מכל ארח רע כלאתי רגלי למען אשמר דברך׃

קב ממשפטיך לא סרתי; כי אתה הורתני׃

קג מה נמלצו לחכי אמרתך מדבש לפי׃

קד מפקודיך אתבונן; על כן שנאתי כל ארח שקר׃

מאיבי תחכמני מצותך is generally translated as “Thy commandments make me wiser than mine enemies”, and לעולם היא לי refers back to תורתך. I am always learning Torah, so your commandments make me wise. But we know how the Mishna translates the next line:

איזהו חכם? הלומד מכל אדם, שנאמר:(תהלים קיט;צט): ”מכל מלמדי השכלתי כי עדותיך שיחה לי“.

The מִ־ means “from”, not “more than”. This is a common ambiguity in תנ״ך; when Avimelech complains about Isaac’s wealth, he says:

ויאמר אבימלך אל יצחק; לך מעמנו כי עצמת ממנו מאד׃

Is it “You are richer than we are” or “You became rich from us—it should be our wealth”? I would read all literary ambiguity as intentional. Both readings are valid. So too here, we could read this as “My enemies made me wise in Your commandments”. Learning from everyone means learning even from those who oppose us. The Kedushas Levi says we learn this from Noah:

אשרי האיש אשר לא הלך בעצת רשעים;

ובדרך חטאים לא עמד ובמושב לצים לא ישב׃

ח ונח מצא חן בעיני ה׳׃

ט אלה תולדת נח נח איש צדיק תמים היה בדרתיו; את האלקים התהלך נח׃

דבר אחר ”אשרי האיש“. מדבר בנח איש צדיק שלא הלך בעצת שלשה דורות דור אנוש ודור המבול ודור הפלגה. על דעתיה דר׳ יהודה דאמר בעצת רשעים זה דור אנוש. ובדרך חטאים דור המבול. ובמושב לצים זה דור הפלגה שהיו כולם ליצנים.

ונח מצא חן בעיני ה׳: דהכלל כל דבר שהצדיק רואה ממנו לוקח עבודת ה׳ ואם רואה חס ושלום איזה אדם מתאוה לעבירה לוקח הצדיק מזה התאוה עבדות ה׳ שאומר בלבו קל וחומר מה זה שמתאוה לדבר עבירה שהוא קלה ונפסד בזמן מועט, מכל שכן שראוי לו להתלהב לעבודת השם יתברך שעבודה זו יקיים לעולם. והיות מקודם נאמר הקרא ויראו בני אלהים את בנות האדם כו׳, שמראה הכתוב שאז היה חן רע בעולם שהנשים היה להם חן בעיני האנשים ומכח זו בחרו להם כל אשר רצו הודיע הכתוב ונח מצא חן, פירוש מצא בעולם מדת חן שהיה לתאות רעות וכו׳. ואמר הכתוב ונח מצא חן בעיני ה׳, שנח הגביה חן ההוא בעיני ה׳ לקדושה שממנו לקח עבדות ה׳ שאמר מה שיש חן לתאות רעות מכל שכן שיהיה אדם משתוקק שימצא חן בעיני ה׳ על ידי עבודתו ותורתו ויראתו ודו״ק.

This is why a wise person learns from everyone. Instead of being corrupted by his evil generation, Noah used it as an opportunity for spiritual growth. He had the “best” teachers available! All Noah had to do was learn to take their ingenuity, arrogance, passion, jealousy and zeal, and use them in a productive, constructive way to get closer to God.

The idea of מכל מלמדי השכלתי, that a חכם learns from everyone, is even more important to teachers:

אמר רב נחמן בר יצחק: למה נמשלו דברי תורה כעץ שנאמר (משלי ג:יח) ”עץ חיים היא למחזיקים בה“? לומר לך מה עץ קטן מדליק את הגדול אף תלמידי חכמים קטנים מחדדים את הגדולים. והיינו דאמר ר׳ חנינא: הרבה למדתי מרבותי ומחבירי יותר מרבותי ומתלמידי יותר מכולן.

ההסבר המקובל לדברים אלו הוא, שכמה שלומדים מן הרבנים, יש קניין נוסף בלימוד עם חברותא, כי בהתעסקות העצמית עם חברו הרי אדם לומד ולא רק מקבל מחברו. וכן כתוב במסכת ברכות שהדרך לקניית תורה אמיתית

היא בחברות…מי שמתעסק בתורה לבדו בלי חברים, לא רק שזה לא מועיל אלא זה גם מזיק. לכן יש מעלה מיוחדת להתעסק בתורה עם חברו.

אבל יתר על כן הלימוד עם תלמידים מרחיב את ההבנה בתורה משתי בחינות: הראשונה שכדי להסביר את הנושא אדם חייב להבהיר לעצמו ביתר שאת את העניינים, הבחינה השנייה היא מעצם שאלות התלמידים, אדם לומד להבין יותר את הסוגיא שהוא עוסק בה.

The Tosfot Yom Tov sees a problem with a parallel mishna earlier in אבות:

…יהושוע בן פרחיה אומר, עשה לך רב, וקנה לך חבר; והוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות.

ובמדרש שמואל כתב בשם ה״ר יהודה לירמ״א שהקשה למה לא הזהיר על שיקח תלמידים שהרי אמרו [תענית ז,א מכות י,א] הרבה למדתי מרבותי וכו׳ ומתלמידי יותר מכולם. ונתן טעם לזה שהתלמידים כל מגמת פניהם הוא ללמוד. לכן אינם לומדים אלא במקום שלבם חפץ בו יותר או ממי שנראה להם שהם לומדים ממנו יותר. ומאחר שלא ימצא האדם מי שירצה להיות תלמיד לו. לכן לא הזהיר התנא עליהם. ע״כ. ורבינו מהר״ר ליווא ז״ל בספר דרך חיים כתב שלא אמר קנה לך תלמיד שאין ראוי לעשות דבר זה לעשות האדם עצמו לרב וליקח לעצמו שם חשיבות לומר תלמוד ממני כמו שעושים בארצות הללו ע״כ.

משה קיבל תורה מסיניי, ומסרה ליהושוע, ויהושוע לזקנים, וזקנים לנביאים, ונביאים מסרוה לאנשי כנסת הגדולה. והן אמרו שלושה דברים: היו מתונים בדין, והעמידו תלמידים הרבה, ועשו סייג לתורה.

ואף על פי שדבריהם האמת והצדק, בעיני נראה שהקושיא מעיקרא לאו קושיא היא לפי שכבר קדמוהו להתנא קמאי דקמאי אנשי כנסת הגדולה שהם אמרו והעמידו תלמידים הרבה.

There’s another possible reason that יהושוע בן פרחיה didn’t want to talk about students (I saw this in a Chabad commentary on Pirkei Avot). There’s an interesting censored paragraph in the Talmud:

כדקטלינהו ינאי מלכא לרבנן אזל רבי יהושע בן פרחיה וישו לאלכסנדריא של מצרים. כי הוה שלמא שלח ליה שמעון בן שטח…קם אתא ואתרמי ליה ההוא אושפיזא; עבדו ליה יקרא טובא. אמר [יהושע בן פרחיה]: כמה יפה אכסניא זו! אמר [ישו] ליה: רבי עיניה טרוטות. אמר ליה: רשע בכך אתה עוסק!…ושמתיה. אתא לקמיה כמה זמנין, אמר ליה קבלן לא הוי קא משגח ביה. יומא חד הוה קא קרי [יהושע בן פרחיה] קריאת שמע, אתא [ישו] לקמיה. סבר [יהושע בן פרחיה] לקבולי. אחוי [יהושע בן פרחיה] ליה בידיה. הוא [ישו] סבר מידחא דחי ליה; אזל זקף לבינתא והשתחוה לה. אמר [יהושע בן פרחיה] ליה הדר בך! אמר [ישו] ליה: כך מקובלני ממך כל החוטא ומחטיא את הרבים אין מספיקין בידו לעשות תשובה. ואמר מר ישו כישף והסית והדיח את ישראל:

(Despite the fact that it was censored for fear of the Church, the ישו here can’t be Jesus; “Alexander Jannaeus (also known as Alexander Jannai/Yannai)…was the second Hasmonean king of Judaea from 103 to 76 BC” [Wikipedia]).

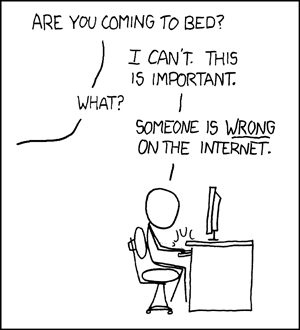

But I would understand יהושוע בן פרחיה's statement as actually being about students, and what is means to say מתלמידי יותר מכולן. The only way to learn from from your students is to accept that they have something to say, that you don’t know everything. הוי דן את כל האדם לכף זכות means allowing that others may not be evil even if I disagree with them, and I need to have the humility to be able to say מאיבי תחכמני מצותך.