This week I want to look at two other תהילים by אסף, but ones that are very different from what we’ve seen before. These are not rebuking Israel but prayers for its salvation. The first is תהילים פרק פג, which we say in times of trouble in modern Israel:

א שיר מזמור לאסף׃

ב אלקים אל דמי לך; אל תחרש ואל תשקט א־ל׃

ג כי הנה אויביך יהמיון; ומשנאיך נשאו ראש׃

ד על עמך יערימו סוד; ויתיעצו על צפוניך׃

ה אמרו לכו ונכחידם מגוי; ולא יזכר שם ישראל עוד׃

ו כי נועצו לב יחדו; עליך ברית יכרתו׃

ז אהלי אדום וישמעאלים; מואב והגרים׃

ח גבל ועמון ועמלק; פלשת עם ישבי צור׃

ט גם אשור נלוה עמם; היו זרוע לבני לוט סלה׃

This is what I would call a “suspiciously specific” perek. By naming each individual nation, he clearly has some actual incident in mind. What incident is harder to tell. It has to be before the time that Assyria was an all-conquering empire, because it describes Assyria as only mercenaries for בני לוט, who presumably are the main antagonists here. It would have to be after the time of David and Solomon, because during their reigns the Phonecians (גבל and צור) were allied with Israel.

The מפורשים find a likely incident in דברי הימים:

המזמור נאמר על המלחמה שהיתה בימי יהושפט כשבאו עליו בני שעיר ועמון ומואב, כמו שאמר בדברי הימים (ב כ:א).

נוסד ג״כ בימי יהושפט שבאו עליו בני מואב ובני עמון למלחמה ועמם המון רב ויהושפט התפלל וקרא צום, ויחזיאל מן בני אסף היתה עליו רוח ה׳ בתוך הקהל ויאמר אל תיראו וכו׳.

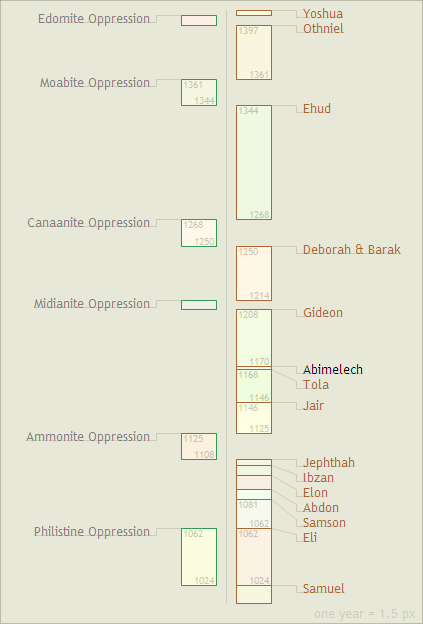

The Kings of the Kingdom of Judah

Based on http://www.seder-olam.info/index.html

| Year | BCE | King |

|---|---|---|

| 2699 | 1060 | Saul |

| 2701 | 1058 | David and Ish Boshet civil war |

| 2708 | 1051 | David |

| 2741 | 1018 | Solomon |

| 2781 | 978 | Rehoboam |

| 2798 | 961 | Abijam |

| 2801 | 958 | Asa |

| 2842 | 917 | Jehoshaphat; peace with Israel |

| 2865 | 894 | Jehoram |

| 2872 | 887 | Ahaziah |

| 2873 | 886 | Athaliah mother of Ahaziah |

| 2879 | 880 | Joash; Athaliah executed |

| 2915 | 844 | Amaziah |

| 2956 | 803 | Azariah |

| 3006 | 753 | Jotham |

| 3022 | 737 | Ahaz |

| 3035 | 724 | Hezekiah; fall of Israel |

| 3064 | 695 | Manasseh |

| 3119 | 640 | Amon |

| 3121 | 638 | Josiah |

| 3152 | 607 | Jehoahaz named king by Pharaoh Necoh |

| 3163 | 596 | Jehoiachin |

| 3163 | 596 | Zedekiah named king by Nebuchadnezzar |

| 3173 | 586 | Zedekiah prisoner; Temple destroyed |

א ויהי אחרי כן באו בני מואב ובני עמון ועמהם מהעמונים על יהושפט למלחמה׃

ב ויבאו ויגידו ליהושפט לאמר בא עליך המון רב מעבר לים מארם; והנם בחצצון תמר היא עין גדי׃

ג וירא ויתן יהושפט את פניו לדרוש לה׳; ויקרא צום על כל יהודה׃

ד ויקבצו יהודה לבקש מה׳; גם מכל ערי יהודה באו לבקש את ה׳׃

ה ויעמד יהושפט בקהל יהודה וירושלם בבית ה׳; לפני החצר החדשה׃

ו ויאמר ה׳ אלקי אבתינו הלא אתה הוא אלקים בשמים ואתה מושל בכל ממלכות הגוים; ובידך כח וגבורה ואין עמך להתיצב׃

ז הלא אתה אלקינו הורשת את ישבי הארץ הזאת מלפני עמך ישראל; ותתנה לזרע אברהם אהבך לעולם׃

ח וישבו בה; ויבנו לך בה מקדש לשמך לאמר׃

ט אם תבוא עלינו רעה חרב שפוט ודבר ורעב נעמדה לפני הבית הזה ולפניך כי שמך בבית הזה; ונזעק אליך מצרתנו ותשמע ותושיע׃

י ועתה הנה בני עמון ומואב והר שעיר אשר לא נתתה לישראל לבוא בהם בבאם מארץ מצרים; כי סרו מעליהם ולא השמידום׃

יא והנה הם גמלים עלינו; לבוא לגרשנו מירשתך אשר הורשתנו׃

יב אלקינו הלא תשפט בם כי אין בנו כח לפני ההמון הרב הזה הבא עלינו; ואנחנו לא נדע מה נעשה כי עליך עינינו׃

יג וכל יהודה עמדים לפני ה׳; גם טפם נשיהם ובניהם׃

יד ויחזיאל בן זכריהו בן בניה בן יעיאל בן מתניה הלוי מן בני אסף; היתה עליו רוח ה׳ בתוך הקהל׃

טו ויאמר הקשיבו כל יהודה וישבי ירושלם והמלך יהושפט; כה אמר ה׳ לכם אתם אל תיראו ואל תחתו מפני ההמון הרב הזה כי לא לכם המלחמה כי לאלקים׃

טז מחר רדו עליהם הנם עלים במעלה הציץ; ומצאתם אתם בסוף הנחל פני מדבר ירואל׃

יז לא לכם להלחם בזאת; התיצבו עמדו וראו את ישועת ה׳ עמכם יהודה וירושלם אל תיראו ואל תחתו מחר צאו לפניהם וה׳ עמכם׃

יח ויקד יהושפט אפים ארצה; וכל יהודה וישבי ירושלם נפלו לפני ה׳ להשתחות לה׳׃

יט ויקמו הלוים מן בני הקהתים ומן בני הקרחים להלל לה׳ אלקי ישראל בקול גדול למעלה׃

כ וישכימו בבקר ויצאו למדבר תקוע; ובצאתם עמד יהושפט ויאמר שמעוני יהודה וישבי ירושלם האמינו בה׳ אלקיכם ותאמנו האמינו בנביאיו והצליחו׃

כא ויועץ אל העם ויעמד משררים לה׳ ומהללים להדרת קדש בצאת לפני החלוץ ואמרים הודו לה׳ כי לעולם חסדו׃

כב ובעת החלו ברנה ותהלה נתן ה׳ מארבים על בני עמון מואב והר שעיר הבאים ליהודה וינגפו׃

כג ויעמדו בני עמון ומואב על ישבי הר שעיר להחרים ולהשמיד; וככלותם ביושבי שעיר עזרו איש ברעהו למשחית׃

כד ויהודה בא על המצפה למדבר; ויפנו אל ההמון והנם פגרים נפלים ארצה ואין פליטה׃

כה ויבא יהושפט ועמו לבז את שללם וימצאו בהם לרב ורכוש ופגרים וכלי חמדות וינצלו להם לאין משא; ויהיו ימים שלושה בזזים את השלל כי רב הוא׃

כו וביום הרבעי נקהלו לעמק ברכה כי שם ברכו את ה׳; על כן קראו את שם המקום ההוא עמק ברכה עד היום׃

כז וישבו כל איש יהודה וירושלם ויהושפט בראשם לשוב אל ירושלם בשמחה; כי שמחם ה׳ מאויביהם׃

כח ויבאו ירושלם בנבלים ובכנרות ובחצצרות אל בית ה׳׃

כט ויהי פחד אלקים על כל ממלכות הארצות; בשמעם כי נלחם ה׳ עם אויבי ישראל׃

ל ותשקט מלכות יהושפט; וינח לו אלקיו מסביב׃

That’s the story, and there are two things that make Radak and Malbim connect it to our perek. First is the נביא: זכריהו…מן בני אסף. If we’re attributing this to the time of יהושפט, then it can’t be literally written by אסף himself, but we could say that this perek is a prayer of the נביא of the time and מזמור לאסף is a dedication to his ancestor. Second is the nature of the war, and the fight against בני עמון ומואב והר שעיר fits with the mention of all those nations in תהילים פרק פג.

Let’s look at the perek in more detail.

אל דמי לך; אל תחרש ואל תשקט

The Malbim points out that the three terms דמי, תחרש and תשקט are different. דום is used in the sense of inanimate, the opposite of חיים. חרש means mute, unspeaking. שקט in תנ״ך doesn’t mean silent, but quiet in the sense of still, peaceful (ותשקט הארץ ארבעים שנה doesn’t mean that nobody spoke). So the sense of the pasuk is and escalating plea: ה׳ don’t be דום; feel something! Don’t be חרש; say something! And don’t be שקט; do something!

נועצו לב יחדו

Why? Because all the surrounding nations are conspiring together. We have no earthly allies. נכחיד means extinct; they are trying to eliminate Israel as a people.

אהלי אדום וישמעאלים

And who are these surrounding nations? The author lists just about everyone, from the well-known to the most obscure. He starts with אדום and ישמעאל, the people most closely related to us (יעקב‘s and יצחק’s brothers, respectively), who would be hoped to be more sympathetic. Instead, they are leading the camp. מואב, עמון, עמלק and פלשת we know. צור is a Phoenician city; in תנ״ך the Phoenicians are considered allies of the Philistines. גבל is mentioned one other time in תנ״ך, in יחזקאל כז:ט as one of the Phoenician cities. It is usually identified as Byblos in northern Lebanon. הגרים is more of a mystery (it’s “Hagrites”, not “the Grim”, by the way). Presumably they are the הגריאים mentioned in דברי הימים:

יח בני ראובן וגדי וחצי שבט מנשה מן בני חיל אנשים נשאי מגן וחרב ודרכי קשת ולמודי מלחמה ארבעים וארבעה אלף ושבע מאות וששים יצאי צבא׃

יט ויעשו מלחמה עם ההגריאים ויטור ונפיש ונודב׃

כ ויעזרו עליהם וינתנו בידם ההגריאים וכל שעמהם; כי לאלהים זעקו במלחמה ונעתור להם כי בטחו בו׃

Which would put them in modern eastern Jordan. It is usually assumed that they were descended from Hagar, Avraham’s wife. If she is identified with Keturah, then we have a list of nations besides Ishmael:

א ויסף אברהם ויקח אשה ושמה קטורה׃

ב ותלד לו את זמרן ואת יקשן ואת מדן ואת מדין ואת ישבק ואת שוח׃

ג ויקשן ילד את שבא ואת דדן; ובני דדן היו אשורם ולטושם ולאמים׃

גם אשור נלוה עמם

Assyria at this time (even in the time of יהושפט) was not the world-dominating empire it would become. Here they are just mercenaries for the other enemies of Israel. Rashi points out that the last time אשור was mentioned, they were good guys:

ח וכוש ילד את נמרד; הוא החל להיות גבר בארץ׃

ט הוא היה גבר ציד לפני ה׳; על כן יאמר כנמרד גבור ציד לפני ה׳׃

י ותהי ראשית ממלכתו בבל וארך ואכד וכלנה בארץ שנער׃

יא מן הארץ ההוא יצא אשור; ויבן את נינוה ואת רחבת עיר ואת כלח׃

אף אשור שהיה נזהר עד היום משאר עצה סכלה ולא יתחבר עם מרעים כמה דאת אמר (בראשית י) מן הארץ ההיא יצא אשור שיצא מעצת דור הפלגה, כאן נלוה עמם ועזרם לרעה.

One nation that is strikingly missing is Aram, the major enemy of Israel throughout the early first Temple period; this goes with the story of Jehoshaphat where the enemy comes from the area of Aram but Aram itself is not mentioned.

The question that we’ve avoided is how could this be a prayer for a war in the time of יהושפט if ספר תהילים was written by David? We know the gemara:

דוד כתב ספר תהלים ע״י עשרה זקנים: ע״י אדם הראשון, על ידי מלכי צדק, ועל ידי אברהם, וע״י משה, ועל ידי הימן, וע״י ידותון, ועל ידי אסף, ועל ידי שלשה בני קרח.

But we’ve mentioned the שיר השירים רבה that puts a much later date on the final composition of תהילים:

עשרה בני אדם אמרו ספר תהלים, אדם הראשון, ואברהם, משה, ודוד, ושלמה, על אילין חמשה לא איתפלגון. אילין חמשה אחרנייתא מאן אינון?…רב אמר אסף והימן וידותון ושלשה בני קרח ועזרא.

So according to that view, there’s no problem with dating פרק פג to the post-David era. The Malbim takes this view:

כל עוד התהלך רוח ה׳ בארץ וישכון כבוד על נביאיו וחוזיו…לדבר או לשורר ברוח הקדש, שערי האוצר הזה לא סוגרו, כי עוד הוסיפו זקני דור דור למלא אסמיו תבואת הדורות, בין שתילי ימי קדם, כמו תפלה למשה איש האלקים, בין מטעי אנשי הרוח הבאים אחריו, שיר המעלות לשלמה…מזמור למנשה בן חזקיהו אחרי שב לאלקי אבותיו (תהילים סו), הלל הגדול על נס סנחריב, נגינות אסף על נס זה (תהילים עו)…עד התפלות אשר יסדו בגלות בבל על שרפת המקדש ועל הגלות, עד שוב ה׳ את שיבת ציון בימי כורש (תהילים קלז ו־פה).

However, he adds a very interesting footnote:

…כתבתי זאת לגול מעלינו טענות המלעיגים לאמר איך יתכן כי בימי דוד בעוד המלכות על תקפה וישראל על אדמתם ועוד לא נגזרה גזירה וכבר שרו על הדוכן ביטול המלכות וגלות צדקיהו…וישיבתם על נהרות בבל וקללתם את בבל ואת בני אדום אשר עוד לא חטאו ולא הרשיעו וכדומה מאלה הטענות; ועל כן פרשתי לפי הפשט לסתום פה המעוררים…כל זה כפי דרך הפשט אשר במסלתו הלכנו בפירושנו זה אשר שמתי לי למטרה לכונן חצי נגד להקת המבארים אשר כוונתם להשפיל כבוד כתבי קודש. אולם אצלנו אמונה אומן כי שבעים פנים לתורה וכפי דרך הדרוש והרמז והקבלה, כל המזמורים הללו כבר צפו במחזה הנביאים והמשוררים בני קרח ואסף בימי דוד והיו גנוזים וצפונים ביד אנשי הרוח דור דור עד עת שיצא הדבר אל הפועל ואז נאמרו בקול רם על הדוכן כל אחת בשעתה…אולם להבין הכתובים כפי הפשט והמליצה לא יגרע הדרת הכתובים וכחם אם יסד אותם איש הרוח מבני לוי בימי דוד או בימי חזקיהו וכדומה…וכן תוכל לאמר בכל אלה, שתחלה נאמרו בסתר בימי קדם וחזרו ויסדום בגלוי ונמסרו לכל עדת ישראל בקדושת הכתובים, ודי בהערה זו.

Malbim’s entire commentary takes the first approach. Which one he personally believed I do not pretend to know; Neither approach is כופר בעיקר, and I will not mind if you choose one or leave it undecided. For the purposes of this shiur I would assume that this perek is late, largely because it does not read like a נבואה. A prophecy of the distant future should be a warning (“repent or the temple will be destroyed!”), not a תפלה for salvation from something that has not yet happened.

I think there’s a position between the two extremes. We say פרק פג for trouble in ארץ ישראל, even though the names of the nations have changed. We take the names symbolically, and if we look carefully at the perek, only psukim 7-9 are “localized”. The rest of the perek would apply to any צרות in Israel. So we have an opening for an approach suggested by the Malbim:

למנצח לדוד;

אמר נבל בלבו אין אלקים;

השחיתו התעיבו עלילה אין עשה טוב׃

א למנצח על מחלת משכיל לדוד׃

ב אמר נבל בלבו אין אלקים;

השחיתו והתעיבו עול אין עשה טוב׃

מזמור זה הוכפל בספר זה (נ״ג), עם קצת שינוי, והתבאר אצלי, שמזמור זה אמרו דוד על נס שנעשה לו…וכאשר בא נס סנחריב בימי חזקיה ראו שמזמור זה טוב להודות בו גם על נס זה ותקנוהו עם הוספה קצת ויחסוהו לדוד כי הוא תקנו

So פרק נג was based on an original psalm of David, adapted for the occasion, and still attributed to David. I would say the same thing about our perek. It may have been written by Asaf, without the section about the nations. You could insert the relevant names (like we do with מי שברך or א־ל מלא). This version was recorded for posterity because it resulted in a miracle:

With that, let’s conclude the perek.

י עשה להם כמדין; כסיסרא כיבין בנחל קישון׃

יא נשמדו בעין דאר; היו דמן לאדמה׃

יב שיתמו נדיבימו כערב וכזאב; וכזבח וכצלמנע כל נסיכימו׃

יג אשר אמרו נירשה לנו את נאות אלקים׃

יד אלקי שיתמו כגלגל; כקש לפני רוח׃

טו כאש תבער יער; וכלהבה תלהט הרים׃

טז כן תרדפם בסערך; ובסופתך תבהלם׃

יז מלא פניהם קלון; ויבקשו שמך ה׳׃

יח יבשו ויבהלו עדי עד; ויחפרו ויאבדו׃

יט וידעו כי אתה שמך ה׳ לבדך;

עליון על כל הארץ׃

עשה להם כמדין, כסיסרא כיבין

The author then mentions the two previous miraculous battles, from ספר שופטים. The battle of סיסרא and יבין in נחל קישון is the story of דבורה:

ב וימכרם ה׳ ביד יבין מלך כנען אשר מלך בחצור; ושר צבאו סיסרא והוא יושב בחרשת הגוים׃

ג ויצעקו בני ישראל אל ה׳; כי תשע מאות רכב ברזל לו והוא לחץ את בני ישראל בחזקה עשרים שנה׃

…

טו ויהם ה׳ את סיסרא ואת כל הרכב ואת כל המחנה לפי חרב לפני ברק; וירד סיסרא מעל המרכבה וינס ברגליו׃

טז וברק רדף אחרי הרכב ואחרי המחנה עד חרשת הגוים; ויפל כל מחנה סיסרא לפי חרב לא נשאר עד אחד׃

The battle with מדין is less familiar. It is the story of גדעון:

ויעשו בני ישראל הרע בעיני ה׳; ויתנם ה׳ ביד מדין שבע שנים׃

א וישכם ירבעל הוא גדעון וכל העם אשר אתו ויחנו על עין חרד; ומחנה מדין היה לו מצפון מגבעת המורה בעמק׃

ב ויאמר ה׳ אל גדעון רב העם אשר אתך מתתי את מדין בידם; פן יתפאר עלי ישראל לאמר ידי הושיעה לי׃

…

כב ויתקעו שלש מאות השופרות וישם ה׳ את חרב איש ברעהו ובכל המחנה; וינס המחנה עד בית השטה צררתה עד שפת אבל מחולה על טבת׃

כג ויצעק איש ישראל מנפתלי ומן אשר ומן כל מנשה; וירדפו אחרי מדין׃

ג בידכם נתן אלקים את שרי מדין את ערב ואת זאב ומה יכלתי עשות ככם; אז רפתה רוחם מעליו בדברו הדבר הזה׃

ד ויבא גדעון הירדנה; עבר הוא ושלש מאות האיש אשר אתו עיפים ורדפים׃

…יא ויעל גדעון דרך השכוני באהלים מקדם לנבח ויגבהה; ויך את המחנה והמחנה היה בטח׃

יב וינסו זבח וצלמנע וירדף אחריהם; וילכד את שני מלכי מדין את זבח ואת צלמנע וכל המחנה החריד׃

Unfortunately, no one has any idea what עין דאר has to to with either battle (it’s a city in the north of Israel, between the lands of מנשה and יששכר) Presumably that was the city where one of these battles took place; we just don’t have that information.

They (סיסרא and מדין) were destroyed when they tried to conquer נאות אלקים. Artscroll translates נאות as “pleasant habitations”, a portmanteau word from נאה, pleasant, and נוה, sanctuary. It’s a term used in תנ״ך for the בית המקדש.

שיתמו כגלגל

So to may our current enemies be destroyed. גלגלת, wheel, in this context means “tumbleweed”, like straw scattered in the wind to be consumed in the fire that destroys entire mountains.

יבשו ויבהלו

Rav Hirsch translates יֹאבֵדוּ not as “they will be lost” but as a consequence of יַחְפְּרוּ, their shame, they will feel lost, as their hopes go down in flames.

There’s a sense of anticlimax here, as we go from אש and להבה to סערה and סופה to קלון to בושה. I think that is intentional, and it’s something we see throughout תהילים. The author is trying to de-escalate our emotions. We’re not supposed to read this perek and be fired up to rush out and riot with torches and pitchforks. We look to ה׳ for help. Reacting in anger only makes the situation worse.

וידעו כי אתה שמך ה׳

Because the goal is not the destruction of our enemies but their conversion to allies, in a world where ה׳ is acknowledged as עליון על כל הארץ.

The second perek of מזמור לאסף is clearly about an event far in the future of the historical אסף:

א מזמור לאסף;

אלקים באו גוים בנחלתך טמאו את היכל קדשך;

שמו את ירושלם לעיים׃

ב נתנו את נבלת עבדיך מאכל לעוף השמים;

בשר חסידיך לחיתו ארץ׃

ג שפכו דמם כמים סביבות ירושלם; ואין קובר׃

ד היינו חרפה לשכנינו; לעג וקלס לסביבותינו׃

ה עד מה ה׳ תאנף לנצח; תבער כמו אש קנאתך׃

ו שפך חמתך אל הגוים אשר לא ידעוך;

ועל ממלכות אשר בשמך לא קראו׃

ז כי אכל את יעקב; ואת נוהו השמו׃

ח אל תזכר לנו עונת ראשנים;

מהר יקדמונו רחמיך כי דלונו מאד׃

ט עזרנו אלקי ישענו על דבר כבוד שמך;

והצילנו וכפר על חטאתינו למען שמך׃

י למה יאמרו הגוים איה אלקיהם;

יודע בגיים (בגוים) לעינינו; נקמת דם עבדיך השפוך׃

יא תבוא לפניך אנקת אסיר; כגדל זרועך הותר בני תמותה׃

יב והשב לשכנינו שבעתים אל חיקם;

חרפתם אשר חרפוך א־דני׃

יג ואנחנו עמך וצאן מרעיתך נודה לך לעולם;

לדור ודר נספר תהלתך׃

כתיב (תהלים עט) מזמור לאסף אלקים באו גוים בנחלתך, לא הוה קרא צריך למימר אלא בכי לאסף נהי לאסף קינה לאסף, ומה אומר מזמור לאסף, אלא משל למלך שעשה בית חופה לבנו וסיידה וכיידה וציירה ויצא בנו לתרבות רעה, מיד עלה המלך לחופה וקרע את הוילאות ושיבר את הקנים ונטל פדגוג שלו איבוב של קנים והיה מזמר, אמרו לו המלך הפך חופתו של בנו ואת יושב ומזמר, אמר להם מזמר אני שהפך חופתו של בנו ולא שפך חמתו על בנו, כך אמרו לאסף הקדוש ברוך הוא החריב היכל ומקדש ואתה יושב ומזמר, אמר להם מזמר אני ששפך הקדוש ברוך הוא חמתו על העצים ועל האבנים ולא שפך חמתו על ישראל.

The idea of נתנו את נבלת עבדיך מאכל לעוף השמים is from the תוכחה:

והיתה נבלתך למאכל לכל עוף השמים ולבהמת הארץ; ואין מחריד׃

אסף sees the חורבן as a fulfillment of ה׳'s word. While he laments the reality, he can’t claim it is a surprise. But the extent of the cruelty of the enemy makes all of Israel martyrs:

תדע דכתיב (תהילים עט) ”מזמור לאסף אלקים באו גוים בנחלתך טמאו את היכל קדשך [וגו׳] נתנו את נבלת עבדיך מאכל לעוף השמים בשר חסידיך לחיתו ארץ“ מאי עבדיך ומאי חסידיך לאו חסידיך חסידיך ממש עבדיך הנך דמחייבי דינא דמעיקרא וכיון דאיקטול קרי להו עבדיך.

Why do we call them all kedoshim, when so many of them had been vehemently anti-religious and had helped destroy the foundations of Torah in Europe?

Consider, for example, the most ironic situation imaginable: a young Jew, born of Jewish mother and Catholic father, raised as a Catholic, is kneeling in a church, quietly murmuring his paternoster, perhaps even offering a prayer for the well-being of the brave German soldiers. In come two soldiers and drag him off to the death camps, while he protests all along that he is a good Catholic, and not a Jew. Is he also one of the six million kedoshim?

קלס is an interesting word. It usually means “praise”.

[E]ven as קלס denotes the praise…or glorification of another, it could also mean the glorification or praise of self…We became לעג and קלס to them; they scorned us and exalted themselves. To them our degredation was a cause for self-praise. To deride the Jew was considered part of the glory of the nations.

תאנף לנצח

Again, אסף assumes that what happens is due to ה׳'s anger at us. The assumption is that ה׳ cares, and the destruction is what we deserve. The prayer is that it eventually ends, and that ה׳ recognizes that the enemy has gone too far.

We don’t take revenge ourselves but ask that ה׳ do it. It is what we say at the seder every year when we open the door for Eliyahu. Rabbi Eli Baruch Shulman (Rabbi Shulman’s brother) in הגדה ישמח אב has an interesting explanation for why we quote these psukim:

We have to look at the seder as described in the Mishna:

ה רבן גמליאל אומר, כל שלא אמר שלושה דברים אלו בפסח, לא יצא ידי חובתו; ואלו הן—פסח, מצה, ומרורים…בכל דור ודור, חייב אדם לראות את עצמו כאילו הוא יצא ממצריים; לפיכך אנחנו חייבין להודות להלל לשבח לפאר להדר לרומם לגדל לנצח למי שעשה לנו את כל הניסים האלו, והוציאנו מעבדות לחירות. ונאמר לפניו, הללוי־ה.

ועד איכן הוא אומר—בית שמאי אומרין, עד “אם הבנים, שמחה” (תהילים קיג,ט); בית הלל אומרין, עד ”חלמיש, למעיינו מים“ (תהילים קיד,ח). וחותם בגאולה…ברוך אתה ה׳, גאל ישראל.

ז מזגו לו כוס שלישי, בירך על מזונו; רביעי, גומר עליו את הלל….

Why do we split הלל up like this, part before ברכת המזון and part after? הלל on the seder night is different from other times we say הלל:

אבל רבינו האי גאון ז״ל כתב בתשובה שאין מברכין על הלל שבלילי פסחים לגמור את ההלל שאין אנו קוראין אותו בתורת קורין אלא בתורת אומר שירה שכך שנינו ר״ג אומר וכו׳ ובסיפא לפיכך אנו חייבין להודות להלל וכו׳ לפיכך אם בא אדם לברך משתקין אותו אלו דברי הגאון ז״ל.

The fact that this הלל is a שירה means that it is supposed to be the spontaneous outpouring of emotion. חייב אדם לראות את עצמו כאילו הוא יצא ממצריים; לפיכך אנחנו חייבין…[ל]אמר לפניו הללוי־ה. It doesn’t have the limitations that the ritualized קריאת ההלל has. So we’re allowed to split it up. But why do it? Why not say all of it now?

אמר רב משום רבי חייא: כזיתא פסחא, והלילא פקע איגרא.

מאי לאו? דאכלי באיגרא ואמרי באיגרא! לא; דאכלי בארעא ואמרי באיגרא.

In his recently published Haggadah Yesamach Av Rav Eliyahu B. Shulman offers a simple but fascinating historically-based explanation׃ The Gemara (Pesachim 85b-86a) says that in the time of the Temple Hallel split the roofs of Jerusalem׃ Even though people were not allowed to eat the Pesach sacrifice on their roofs they would eat the meal inside their homes and then go onto their roofs to sing Hallel׃ Imagine the entire city full of families singing on their roofs.

…

On the one hand, we need to recite Hallel over the Pesach sacrifice, which was the meal. On the other hand, people wanted to say Hallel on the roofs. Therefore, we start Hallel before the meal, say a little, eat the meal, and then finish Hallel (in Temple times on the rooftops).

Rav Shulman quotes Rav Shmuel Baruch Eliezrov, who in his Devar Shmuel (Pesachim 86a) says that his grandfather, Rav Yosef Salant, used this historical practice to explain our current practice of opening our door for “Pour out Your wrath.” The Pesach sacrifice has to be eaten in the home, with the group. Therefore, people would close their doors to ensure that everyone ate the food in the correct place. After they finished eating, they opened their doors to go up to their roofs and sing Hallel. We open our doors in commemoration of the ancient practice of singing Hallel on the rooftops.

So that nicely explains the custom of opening the doors. But what about שְׁפֹךְ חֲמָתְךָ?

Rav Shulman adds that nowadays we open our doors and see that we are in exile, not Jerusalem, and in our grief ask God to avenge our plight.

This is when we sing הלל של שירה. If we are truly in the moment, we should feel it. We open our doors to join with the rest of בני ישראל in ירושלים, but then we look out and see…St. Louis. We’ve even poured the fifth cup, for the fifth לשון גאולה and we invoke אליהו, the harbinger of גאולה:

הנה אנכי שלח לכם את אליה הנביא לפני בוא יום ה׳ הגדול והנורא׃

But it does no good. Our anticipation of singing הלל is dashed.

So we break out with this perek, the מזמור לאסף that is the antithesis of הלל, a song not of thanksgiving but of vengeance. We say four psukim and we get back under control and realize we still need to show הכרת הטוב to ה׳ (that’s the meaning of דיינו), and finish our הלל.

אל תזכר לנו עונת ראשנים

אסף asks ה׳ not to remember עונת ראשנים. As we’ve said before, we can be punished for the sins of our ancestors when they become part of our culture:

אבל זהו [חטאים פרטיים] רק חלק קטן של העבירות. נוסף על זה יש סוג אחר של עבירות שאותן אני עובר אותם לא כעבירות אישיות שלי, אלא מפני שכך עושים בתוך מבנה החיים שבו אני נולדתי וגדלתי.

אסף is asking that we be spared this, כי דלונו מאד. We can’t handle any more.

א שאַנד פֿאַר די גויים

And the defense is something the נביאים have used before: destroying Israel would be a חילול ה׳:

יא ויחל משה את פני ה׳ אלקיו; ויאמר למה ה׳ יחרה אפך בעמך אשר הוצאת מארץ מצרים בכח גדול וביד חזקה׃

יב למה יאמרו מצרים לאמר ברעה הוציאם להרג אתם בהרים ולכלתם מעל פני האדמה; שוב מחרון אפך והנחם על הרעה לעמך׃

יג זכר לאברהם ליצחק ולישראל עבדיך אשר נשבעת להם בך ותדבר אלהם ארבה את זרעכם ככוכבי השמים; וכל הארץ הזאת אשר אמרתי אתן לזרעכם ונחלו לעלם׃

יד וינחם ה׳ על הרעה אשר דבר לעשות לעמו׃

Note the pun of the קרי/כתיב of בגיים (the arrogant) and בגוים (the nations). It is their arrogance in asking איה אלקיהם that is the חילול ה׳, that makes it critical that ה׳ should be acknowledged.

שבעתים

אסף asks for ה׳'s vengeance specifically on שכנינו; all the nations of the Middle East were conquered by Babylon, so we hoped that they would be sympathetic. But instead they cheered as the Temple was destroyed:

זכר ה׳ לבני אדום את יום ירושלם;

האמרים ערו ערו עד היסוד בה׃

“Sevenfold” is a common expression for “a lot”:

ויאמר לו ה׳ לכן כל הרג קין שבעתים יקם; וישם ה׳ לקין אות לבלתי הכות אתו כל מצאו׃

אִמְרוֹת ה׳ אֲמָרוֹת טְהֹרוֹת;

כֶּסֶף צָרוּף בַּעֲלִיל לָאָרֶץ; מְזֻקָּק שִׁבְעָתָיִם׃

נודה לך לעולם

The Radak points out that the last pasuk is not conditional. We praise ה׳ whether or not we are saved.

ואנחנו עמך, בין בגלות בין בצאתנו מהגלות נודה לך לעולם