After everything we’ve seen, the Givonim have been given everything they want. Justice, however cruel, has been served. We would expect that ה׳ would bring the rain and end the drought. But that’s not what happens. Instead, we hear of the mother of two of the men who were killed, רצפה בת איה, Saul’s concubine:

ותקח רצפה בת איה את השק ותטהו לה אל הצור מתחלת קציר עד נתך מים עליהם מן השמים; ולא נתנה עוף השמים לנוח עליהם יומם ואת חית השדה לילה׃

And even this נתך מים עליהם מן השמים didn’t really end the drought; we are told ויעתר אלקים לארץ אחרי כן after another four psukim.

ומה שאמר ”עד נתך המים עליהם“ ירדו גשמים מעט להודיע שיקברו אותם, ואחר שקברו אותם נעתר האלקים לארץ וירדו גשמים הרבה כמ״ש ”ויעתר אלקים לארץ אחרי כן“.

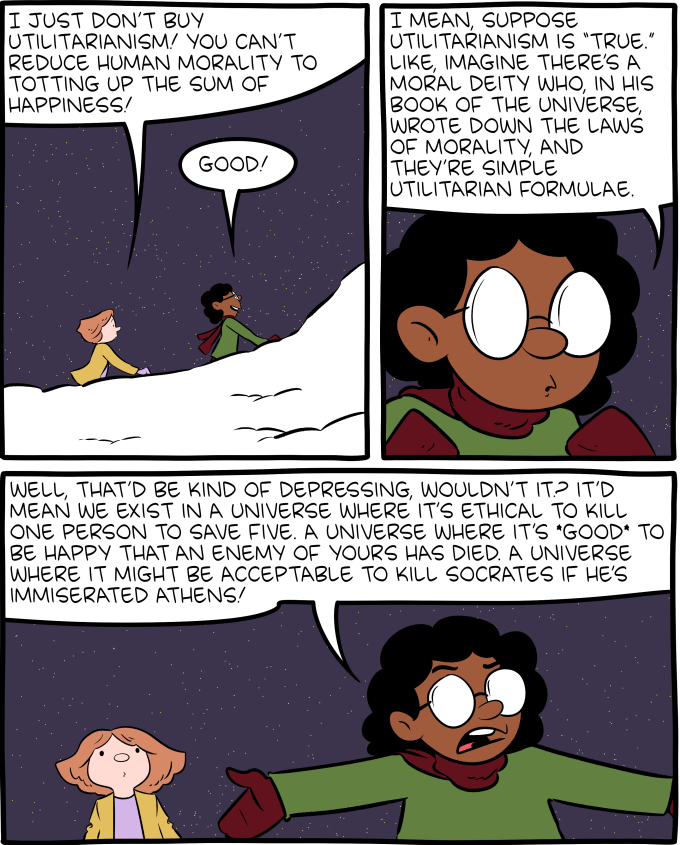

Levinas says we are told of רצפה's dedication because it’s too easy to lose sight of the fundamental fact that after all the discussion of justice and forgiveness, of revenge and reparations, we are talking about human beings. Kings need to deal with the trolley problem, and sacrifice the few for the good of the many, but it’s not some algebraic calculation. Utilitarian ethics lead to repugnant conclusions where everyone suffers to make some abstract “total happiness” higher (ואכמ״ל). If I deal with a trolley problem, however I determine necessary, and then think I have solved it, then I am fundamentally immoral.

And what remains as well, after this somber vision of the human condition and of Justice itself, what rises above the cruelty inherent in rational order (and perhaps simply in Order), is the image of this woman, this mother, this Rizpah Bat Aiah, who, for six months watches over the corpses of her sons, together with the corpses that are not her sons, to keep from the birds of the air and the beasts of the fields, the victims of the implacable justice of men and of G-d. What remains after so much blood and tears shed in the name of immortal principles is individual sacrifice, which amidst the dialectical rebounds of justice and all its contradictory aboutfaces, without any hesitation, finds a straight and sure way.

And David learns the lesson:

יא ויגד לדוד את אשר עשתה רצפה בת איה פלגש שאול׃ יב וילך דוד ויקח את עצמות שאול ואת עצמות יהונתן בנו מאת בעלי יביש גלעד אשר גנבו אתם מרחב בית שן אשר תלום (תלאום) שם הפלשתים (שמה פלשתים) ביום הכות פלשתים את שאול בגלבע׃ יג ויעל משם את עצמות שאול ואת עצמות יהונתן בנו; ויאספו את עצמות המוקעים׃ יד ויקברו את עצמות שאול ויהונתן בנו בארץ בנימן בצלע בקבר קיש אביו ויעשו כל אשר צוה המלך; ויעתר אלקים לארץ אחרי כן׃

We need to remember the relationship between Saul and the people of יביש גלעד. His first act as king had been to save them from the Ammonites:

א ויעל נחש העמוני ויחן על יביש גלעד; ויאמרו כל אנשי יביש אל נחש כרת לנו ברית ונעבדך׃…ז ויקח צמד בקר וינתחהו וישלח בכל גבול ישראל ביד המלאכים לאמר אשר איננו יצא אחרי שאול ואחר שמואל כה יעשה לבקרו; ויפל פחד ה׳ על העם ויצאו כאיש אחד׃ ח ויפקדם בבזק; ויהיו בני ישראל שלש מאות אלף ואיש יהודה שלשים אלף׃

…יא ויהי ממחרת וישם שאול את העם שלשה ראשים ויבאו בתוך המחנה באשמרת הבקר ויכו את עמון עד חם היום; ויהי הנשארים ויפצו ולא נשארו בם שנים יחד׃

And they returned the favor by burying him after he was killed by the Philistines:

ח ויהי ממחרת ויבאו פלשתים לפשט את החללים; וימצאו את שאול ואת שלשת בניו נפלים בהר הגלבע׃ ט ויכרתו את ראשו ויפשטו את כליו; וישלחו בארץ פלשתים סביב לבשר בית עצביהם ואת העם׃ י וישימו את כליו בית עשתרות; ואת גויתו תקעו בחומת בית שן׃ יא וישמעו אליו ישבי יביש גלעד את אשר עשו פלשתים לשאול׃ יב ויקומו כל איש חיל וילכו כל הלילה ויקחו את גוית שאול ואת גוית בניו מחומת בית שן; ויבאו יבשה וישרפו אתם שם׃ יג ויקחו את עצמתיהם ויקברו תחת האשל ביבשה; ויצמו שבעת ימים׃

And now we are told that David takes the bones of Saul and gives them a royal funeral, something that conspicuously had not happened before. I have to confess: I lied about ה׳ message to David at the beginning of the perek. It wasn’t just about the Givonim:

ויהי רעב בימי דוד שלש שנים שנה אחרי שנה ויבקש דוד את פני ה׳;

ויאמר ה׳ אל שאול ואל בית הדמים על אשר המית את הגבענים׃

The gemara says that אל שאול ואל בית הדמים refer to two different things:

”אל שאול“—שלא נספד כהלכה, ”ואל בית הדמים“—”-על אשר המית הגבעונים-“…אמר דוד: שאול, נפקו להו תריסר ירחי שתא, ולא דרכיה למספדיה. בנתינים ניקרינהו ונפייסינהו.

תריסר ירחי שתא: לאו דוקא דהא קרוב לתלתין שנין הוא שהרי סוף שנותיו של דוד היה, אלא לפי שאין דרך כבוד לספוד אחר י״ב חודש אחר שנתקבלו תנחומין על המת, כדאמר במועד קטן (דף כא,ב).

ה׳ gave the message to David that he needs to correct the injustice to the Givonim, which we have seen, and also to give Saul the honor that he deserved. David figured that its too late to do anything about Saul, so he ignored that (as we did).

אל שאול שלא נספד כהלכה: וראיה לזה דאחר שעשה משפט הגבעונים מבני שאול כתיב ”וילך דוד ויקח את עצמות שאול כו׳“ ”ויקברו כו׳“ ”ויעתר אלהים לארץ“ אח״כ.

The gemara points out the inherent contradiction between honoring Saul and simultaneously exacting punishment for his mistreatment of the Givonim, but it’s not a contradiction. It’s part of being human. Saul was both very good and very bad, and both need to be acknowledged.

קא תבע אל שאול שלא נספד כהלכה, וקא תבע על אשר המית הגבעונים?! אין, דאמר ריש לקיש: מאי דכתיב (צפניה ב:ג): בַּקְּשׁוּ אֶת ה׳ כׇּל עַנְוֵי הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר מִשְׁפָּטוֹ פָּעָלוּ, באשר משפטו—שם פעלו.

דרשו דכינוי ד”משפטו פעלו“ קאי על האדם הנדון דבמקום משפטו של האדם שם נזכר גם פעלו זכותו.

The gemara in Sanhedrin discusses the question of whether a הספד, a eulogy, is done for the sake of the dead or for the sake of the mourners.

איבעיא להו: הספידא יקרא דחיי הוי או יקרא דשכבי הוי? למאי נפקא מינה? דאמר לא תספדוה לההוא גברא…ת״ש: ר׳ נתן אומר: סימן יפה למת שנפרעין ממנו לאחר מיתה; מת שלא נספד ולא נקבר או שחיה גוררתו או שהיו גשמים מזלפין על מטתו, זהו סימן יפה למת. ש״מ יקרא דשכבי הוא; שמע מינה.

The eulogy is for the dead; the fact that there was no eulogy is a sort of תקנה for Saul’s sins, and now that justice was done to the extent possible, David can try to achieve closure after the civil war with Saul. It was not an insult to rebury and eulogize him so late, but a sign that he has paid the price for his sins and now should be remembered for his greatness.

על שאול: שלא עשיתם עמו חסד ולא נספד כהלכה, אמר לו הקדוש ברוך הוא דוד אינו שאול שנמשח בשמן המשחה, אינו שאול שבימיו לא נעשה עבודת כוכבים בישראל, אינו שאול שחלקו עם שמואל הנביא, ואתה בארץ והוא בחוצה לארץ

The Torah Temimah says that the fact that הספידא יקרא דשכבי isn’t really about the dead at all; it is about demonstrating חסד של אמת, true kindness that cannot be paid back.

ותמת שם מרים. תניא: א״ר אמי: למה נסמכה מיתת מרים לפרשת פרה אדומה? לומר לך, מה פרה אדומה מכפרת אף מיתת צדיקים מכפרת.

והנה בכלל לא נתבאר ערך הענין שמיתת צדיקים מכפרת ומה טעם בדבר, וי״ל כונת הענין ע״פ מ״ש בפדר״א פרק י״ז בענין מיתת שאול דכתיב ביה וַיִּקְבְּרוּ אֶת עַצְמוֹת שָׁאוּל… וַיֵּעָתֵר אֱלֹקִים לָאָרֶץ אַחֲרֵי כֵן, וז״ל, כיון שראה הקב״ה שגמלו לו חסד [שצמו ובכו וספדו לו, כמבואר שם] מיד נתמלא רחמים; שנאמר ”ויעתר אלקים לארץ אחרי כן“ ע״כ. מבואר מזה שלא המיתה עצמה מכפרת אלא האבל והכבוד שנוהגין במיתת צדיקים, כי כבוד זה הוא כבוד ה׳.

And so David and the nation of Israel ends this perek with an understanding of what חסד and משפט really mean, and connects this perek back to the end of פרק ח:

וימלך דוד על כל ישראל; ויהי דוד עשה משפט וצדקה לכל עמו׃