This week’s parasha enumerates the Leviim and sums up their duties:

מו כל הפקדים אשר פקד משה ואהרן ונשיאי ישראל את הלוים; למשפחתם ולבית אבתם׃

מז מבן שלשים שנה ומעלה ועד בן חמשים שנה; כל הבא לעבד עבדת עבדה ועבדת משא באהל מועד׃

מח ויהיו פקדיהם שמנת אלפים וחמש מאות ושמנים׃

מט על פי ה׳ פקד אותם ביד משה איש איש על עבדתו ועל משאו; ופקדיו אשר צוה ה׳ את משה׃

עבדת משא I understand; the previous three paragraphs are all about which Leviim schlep what. But what is עבדת עבדה? The work of work? It’s obviously using polysemous meanings of עבדה, “the work of the service”. But what is it referring to?

The פשט appears to be “all the other work of the משכן”; Leviim can’t offer the sacrifices but they can be involved in other ways:

לעבד עבדת עבדה: הורדת והקמת המשכן המוטלת בשוה על כל הלויים. ועבדת משא הארון והשולחן והמנורה והמזבחות שבני קהת נושאים.

לעבוד עבודת עבודה: שחיטה הפשט ונתוח שהם עבודת הכהנים וזה היו עושין הלוים כדכתיב בעזרא ובדברי הימים וגבי פסח של חזקיהו שהיו הלוים מפשיטין.

However, Rashi says it’s a specific kind of service, unique to the Levi’im: שירה:

עבדת עבדה: הוא השיר במצלתים וכנורות, שהיא עבודה לעבודה אחרת.

ועבודת משא: כמשמעו.

The gemara brings other possible sources for the halacha that the sacrifices required שירה:

אמר רב יהודה אמר שמואל מנין לעיקר שירה מן התורה? שנאמר (דברים יח) ”ושרת בשם ה׳ אלקיו“ איזהו שירות שבשם? הוי אומר זה שירה…

ו וכי יבא הלוי מאחד שעריך מכל ישראל אשר הוא גר שם; ובא בכל אות נפשו אל המקום אשר יבחר ה׳׃

ז ושרת בשם ה׳ אלקיו ככל אחיו הלוים העמדים שם לפני ה׳׃

And another source:

רב מתנה אמר מהכא: (דברים כח:מז) תַּחַת אֲשֶׁר לֹא עָבַדְתָּ אֶת ה׳ אֱלֹקֶיךָ בְּשִׂמְחָה וּבְטוּב לֵבָב. איזו היא עבודה שבשמחה ובטוב לבב? הוי אומר זה שירה…

And Rashi’s source:

א״ר יוחנן מהכא (במדבר ד) ”לעבוד עבודת עבודה“. איזהו עבודה שצריכה עבודה? הוי אומר זו שירה…

And the gemara brings other proofs from throughout תנ״ך. שירה is important.

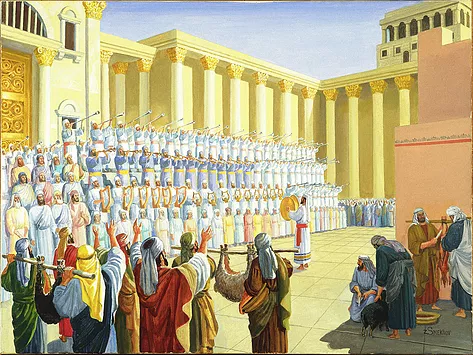

How did the שירה work?

ג ומתיי אומרין השירה: על כל עולות הציבור החובה, ועל שלמי עצרת—בעת ניסוך היין; אבל עולות נדבה שמקריבין הציבור לקיץ המזבח, וכן הנסכין הבאין בפני עצמן—אין אומרין עליהן שירה.

ד …ואין פוחתין משנים עשר לויים עומדים על הדוכן בכל יום, לומר שירה על הקרבן; ומוסיפין עד לעולם. ואין אומרין שירה אלא בפה בלא כלי—שעיקר השירה שהיא עבודתם, בפה.

ה ואחרים היו עומדים שם מנגנין בכלי שיר—מהן לויים ומהן ישראליים…ואין אלו המשוררים על פי הכלים, עולין למניין השנים עשר.

It’s worth noting that the gemara its explanation of עבדת עבדה differently from Rashi. Rashi says עבודה לעבודה אחרת, the song serves the real service. The gemara says its עבודה שצריכה עבודה, the song is the service that needs to be served.

ניתן לקחת דיון זה צעד נוסף הלאה ולשאול מהו היחס המהותי שבין הקרבנות והשירה. האם השירה מהווה אמצעי ליצירת אווירה של שמחה בהקרבת הקרבן, או שמא ההיפך: קרבנות מסוימים…מהווים מכשיר שעל גביו יכולה לבוא השירה המהווה מטרה בפני עצמה? שאלה זו עולה מתוך מקור נוסף לדין שירה שהובא בגמרא:

”לַעֲבֹד עֲבֹדַת עֲבֹדָה, איזהו עבודה שצריכה עבודה? הוי אומר: זו שירה“, שצריכה עבודת נסכים כדי להיאמר.

מן הפסוק עצמו, המכנה את השירה ”עבודת עבודה“, ניתן להבין שהשירה היא רק מכשיר לעבודת הקרבנות. אך בדברי הגמרא נראה שדווקא השירה היא המטרה אשר צריכה עבודה אחרת שתאפשר את אמירתה.

Another way to look at it is that in the Biblical idiom, '“עבדת עבדה” is like “הבל הבלים”, “שיר השירים” or “קודש הקודשים”. It is a superlative, “the highest service” that we are identifying with שירה. And that becomes obvious from a story in the Mishna:

בראשונה, היו מקבלין עדות החודש כל היום; פעם אחת נשתהו העדים מלבוא, ונתקלקלו הלויים בשיר. התקינו שלא יהו מקבלין עדות החודש, אלא עד המנחה; ואם באו עדים מן המנחה ולמעלן, נוהגים אותו היום קדש ולמחר קדש.

ונתקלקלו הלוים בשיר: שלא אמרו שיר כלל אצל נסכי תמיד של בין הערבים. משום דברוב השנים בשחרית לא באו עדיין, להכי תמיד שרו שיר של חול, אבל במנחה ברוב השנים כבר באו העדים, ואמרו המשוררים שיר של יו״ט. אבל באותה שנה שלא באו קודם מנחה, להכי לא ידעו איזה שיר יאמרו. ואחר נסוך הנסכים באו העדים. אמנם לא נתקלקלו שלא הקריבו מוספי ר״ה. דאלו עדיין היו יכולין להקריבן אחר תמיד של בין הערבים.

This was a disaster, so much so that they had to institute a תקנה to prevent it ever happening again. It’s like the chazzan davened the wrong amidah. In fact, it’s exactly like that, which gives us a hint as to the nature of the שירה. Rav Soloveitchik distinuishes between the מעשה of a מצוה and its קיום. The former is the technical act that needs to be done; the latter is the underlying purpose, what the מצוה is meant to accomplish. (We talked about this in the shiur on The Halakhic Mind)

The act (ma’aseh) of prayer is formal, the recitation of a known, set text; but the fulfillment of prayer, its kiyyum, is subjective: it is the service of the heart. The intention (kavvanah) required for prayer is not like the kavvanah required for other mitzvot. In other commandments the intention is not the most important element. It is a secondary element, even it if it required for fulfillment of the mitzvah. Rather it is the act, the concrete action, that is primary, and kavvanah simply accompanies the action. With prayer, however, kavvanah is the essence and substance: prayer without intention is nothing.

Our תפילות correspond to the קרבנות:

רבי יהושע בן לוי אמר: ותפלות כנגד תמידין תקנום

We usually see this as a kind of inferior substitute invented by חז״ל; since we cannot offer קרבנות, then we offer תפילות instead. Or worse:

One of the tragedies of our present communal predicament is that many people who are anxious for spiritual fulfillment are also the most addicted to incessant verbalization…It is as if one were to confess: “Dear G-d, I may not have the patience to pray properly, and I cannot sacrifice my flesh and blood upon Your Altar. I offer You instead my capacity for chatter, and for You I kill my valuable time.”

But seeing שירה as “המטרה אשר צריכה עבודה אחרת שתאפשר את אמירתה” turns this around: the קרבנות exist to allow for תפילה. The קיום of our עבודה, whether קרבן or תפילה, is in our expression of dependence on הקב״ה and so both are versions of the same underlying רצון ה׳.

זֶבַח רְשָׁעִים תּוֹעֲבַת ה׳; וּתְפִלַּת יְשָׁרִים רְצוֹנוֹ׃

ומה שזכר אצל הרשעים זבח ואצל ישרים תפילה, שבא לומר זבח רשעים תועבה אף שאינו מבקש דבר רק שמביא אל השם יתברך קרבן בבלי שום בקשה, עם כל זה תועבה אל השם יתברך, ואלו תפלת ישרים רצונו של השם יתברך אף שהתפילה שהוא מבקש מן השם יתברך הוא לתועלת שלו כמו שהוא כל תפילה, ועם כל זה עבודה הזאת של הישר הוא היא התפלה היא רצונו…

ואין לשאול איך אפשר לומר שהתפלה היא עבודה אל השם יתברך, והרי עבודה זאת על מנת לקבל פרס ואם כן למה נקראת התפלה עבודה. שכבר אמרנו כי כל ענין העבודה מורה שהכל נקנה אל השם יתברך והוא שלו, וכך מורה העבודה של הקרבנות כמו שהתבאר, וכן התפילה שמתפלל לפניו כמו עבד שמתפלל לפני אדון שלו על צרכיו אשר הוא מבקש ובזה נראה כי האדם צריך לו.

The mishna (תמיד ה:א) says that part of the verbal component of the קרבנות, what we are calling שורה, was ברכת העבודה, what we call רצה:

רְצֵה ה׳ אֱלֹקֵינוּ בְּעַמְּךָ יִשְׂרָאֵל וּבִתְפִלָּתָם…וְאִשֵּׁי יִשְׂרָאֵל וּתְפִלָּתָם בְּאַהֲבָה תְּקַבֵּל בְּרָצוֹן…

[W]e find a specific halakhah obligating the priests serving in the Temple to pray at the end of the ritual that the order of worship be accepted as satisfactory. This formula of supplication was transferred from its original place in the Temple ritual to the context of prayer. It is founded on the assumption that the Amidah, too, constitutes an act of sacrificial worship…

The worshipful entreaty persists today as in days of yore. nothing has changed with the destruction of the Temple and the cessation of literal sacrifice. Now too we sacrifice to G-d—that great and awesome offering in which man overcomes his being by ascending to the transcendent metaphysical altar. When a Jew says Retzeh…[h]e asks G-d…to accept his being that is returned to G-d, cleaving unto the Infinite and connecting itself to the Divine throne…From his prayer man emerges firm, elevated and sublime, having found his redemption in self-loss and self-recovery.

That is what the קרבנות were all about, and why the שירה, the תפילה associated with them, was so important.