This is largely a recap of the shiur from תשע״ה, with a slightly different twist. I’d like to look at Golden Calves, but not the one in this week’s parasha (at least not yet). Golden Calves come up in Jewish history:

כו ויאמר ירבעם בלבו; עתה תשוב הממלכה לבית דוד׃

כז אם יעלה העם הזה לעשות זבחים בבית ה׳ בירושלם ושב לב העם הזה אל אדניהם אל רחבעם מלך יהודה; והרגני ושבו אל רחבעם מלך יהודה׃

כח ויועץ המלך ויעש שני עגלי זהב; ויאמר אלהם רב לכם מעלות ירושלם הנה אלהיך ישראל אשר העלוך מארץ מצרים׃

כט וישם את האחד בבית אל; ואת האחד נתן בדן׃

Why Dan and Bethel? Rav Medan proposes that Bethel was the city closest to the site of משכן שילה, so Yeravam was creating his own “בית המקדש” at the historical site of the previous מקדש, before David moved it into his own tribe, into Jerusalem. It was a political move. But where does Dan come from? It comes from the story of פסל מיכה, from the very beginning of the Israelite settlement:

ד וישב את הכסף לאמו; ותקח אמו מאתים כסף ותתנהו לצורף ויעשהו פסל ומסכה ויהי בבית מיכיהו׃

ה והאיש מיכה לו בית אלהים; ויעש אפוד ותרפים וימלא את יד אחד מבניו ויהי לו לכהן׃

א בימים ההם אין מלך בישראל; ובימים ההם שבט הדני מבקש לו נחלה לשבת כי לא נפלה לו עד היום ההוא בתוך שבטי ישראל בנחלה׃

[The army of Dan takes Micha’s idol on their way north] כו וילכו בני דן לדרכם; וירא מיכה כי חזקים המה ממנו ויפן וישב אל ביתו׃

כז והמה לקחו את אשר עשה מיכה ואת הכהן אשר היה לו ויבאו על ליש על עם שקט ובטח ויכו אותם לפי חרב; ואת העיר שרפו באש׃

כח ואין מציל כי רחוקה היא מצידון ודבר אין להם עם אדם והיא בעמק אשר לבית רחוב; ויבנו את העיר וישבו בה׃

כט ויקראו שם העיר דן בשם דן אביהם אשר יולד לישראל; ואולם ליש שם העיר לראשנה׃

ל ויקימו להם בני דן את הפסל; ויהונתן בן גרשם בן מנשה הוא ובניו היו כהנים לשבט הדני עד יום גלות הארץ׃

לא וישימו להם את פסל מיכה אשר עשה כל ימי היות בית האלקים בשלה׃

בימי שמואל בטל, ועז״א כל ימי היות בית אלקים בשילה…ובימי ירבעם שהעמידו העגל בדן היו בניו כהנים עד גלות סנחריב.

So ירבעם set up his two pseudo-temples at the historic sites of previous sanctuaries. I would assume from this that פסל מיכה, even though it is not described explicitly, was an עגל. So basically, the Jews worshipped Golden Calves almost continuously for 664 years (this week’s parasha, then a gap of 40 years in the wilderness, 14 years of Joshua and 40 years of Otniel, the first Judge, then 329 years of שופטים with פסל מיכה, then a gap of 92 years for Shmuel, David and Shlomo, then 241 years of ירבעם's עגלים). The Targum hints at this:

וירא משה את העם כי פרע הוא; כי פרעה אהרן לשמצה בקמיהם׃

Generally we would read קמיהם as “their enemies”, but Onkelos translates it as “generations”:

חֲזָא משֶׁה יָת עַמָא אֲרֵי בְטִיל הוּא אֲרֵי בָטֵילִנוּן אַהֲרֹן לַאֲסָבוּתְהוֹן שׁוּם בִּישׁ לְדָרֵיהוֹן.

It’s worth noting that this was never considered to be idol worship; it’s bad, but not that bad:

א ויהורם בן אחאב מלך על ישראל בשמרון בשנת שמנה עשרה ליהושפט מלך יהודה; וימלך שתים עשרה שנה׃

ב ויעשה הרע בעיני ה׳ רק לא כאביו וכאמו; ויסר את מצבת הבעל אשר עשה אביו׃

ג רק בחטאות ירבעם בן נבט אשר החטיא את ישראל דבק; לא סר ממנה׃

כח וישמד יהוא את הבעל מישראל׃

כט רק חטאי ירבעם בן נבט אשר החטיא את ישראל לא סר יהוא מאחריהם; עגלי הזהב אשר בית אל ואשר בדן׃

So why have a cow? Many say that this was a common form of idolatry in the surrounding cultures, so בני ישראל simply copied them:

אָמַר הֶחָבֵר: כִּי הָאֻמּוֹת כֻּלָּם בַּזְּמָן הַהוּא הָיוּ עוֹבְדִים צוּרוֹת, וְאִלּוּ הָיוּ הַפִּילוֹסוֹפִים, מְבִיאִים מוֹפֵת עַל הַיִּחוּד וְעַל הָאֱלֹהוּת לֹא הָיוּ עוֹמְדִים מִבְּלִי צוּרָה שֶׁמְּכַוְּנִים אֵלֶיהָ וְאוֹמְרִים לַהֲמוֹנָם, כִּי הַצּוּרָה הַזֹּאת יִדְבַּק בָּהּ עִנְיָן אֱלֹהִי וְכִי הִיא מְיֻחֶדֶת בְּדָבָר מֻפְלָא נָכְרִי.

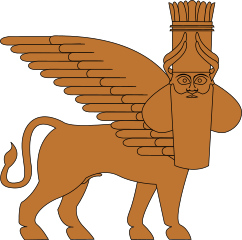

And the bull (especially the winged bull) as a common Mesopotamian theme:

Lama, Lamma or Lamassu…is a Sumerian protective deity…depicted from Assyrian times as a hybrid of a human, bird, and either a bull or lion—specifically having a human head, the body of a bull or a lion, and bird wings

But I think there was more there there. This is one of many times that themes in the Torah seem to be “copied” from older Middle Eastern sources. The academics argue that this proves that the Torah is not divine, but Rav Kook argues that this only proves that the non-Jews got some things right:

וכן כשבאה האשורולוגיה לעולם ונקפה את הלבבות בדמיונים שמצאה, לפי השערותיה הפורחות באוויר, בין תורתנו הקדושה לדברים שבכתבי היתדות, בדעות, במוסר ובמעשים. האם הנקיפה הזאת יש לה מוסד שכלי, אפילו במעט? וכי אין זה דבר מפורסם שהיה בין הראשונים יודעי דעת אלקים, נביאים וגדולי הרוח, מתושלח, חנוך, שם ועבר וכיו״ב, וכי אפשר הוא שלא פעלו כלום על בני דורם? אף על פי שלא הוכרה פעולתם כפעולתו הגדולה של איתן האזרחי אברהם אבינו ע״ה, איך אפשר שלא יהיה שום רושם כלל בדורותם מהשפעותיהם, והלא הם מוכרחים להיות דומים לענייני תורה!

…ובהשקפה היותר בהירה הוא היסוד הנאמן להכרה התרבותית הטובה הנמצאת בעומק טבע האדם, באופן ש”זה ספר תולדות אדם“ הוא כלל כל התורה כולה…

דברים כאלה וכיוצא באלה ראויים הם לעלות על לב כל מבין דבר בהשקפה הראשונה, ולא היה מקום כלל למציאות הכפירה השרלטנית שתתפשט בעולם, ושתתחזק על ידי המאורעות הללו.

So I think that the עגל הזהב represents something more than a familiar idol. It was a familiar idol because it represented something deeper, some profound symbolism:

וחז״ל במדרש תנחומא אמרו שראו את המרכבה ושמטו פני שור מהשמאל ועשו צורתו, וכוונתם כי התבאר אצלי בפירוש מעשה המרכבה שיחזקאל ראה במרכבה הראשונה צורת שור מהשמאל, ובמרכבה השניה ראה תמורתו צורת כרוב.

ודמות פניהם פני אדם ופני אריה אל הימין לארבעתם ופני שור מהשמאול לארבעתן; ופני נשר לארבעתן׃

The כרובים, the “carriers” of the “מרכבה”, of the Divine Presence, are an abstract idea that can’t actually be visualized. But something about the experience of נבואה in the minds of human beings gets translated into images of winged people/animals. And so when they asked of the עגל: קום עשה לנו אלהים אשר ילכו לפנינו, the people were looking for something that represented the כרובים that they had experienced. And that was part of the role of the כרובים that would eventually be commanded:

ויסעו מהר ה׳ דרך שלשת ימים; וארון ברית ה׳ נסע לפניהם דרך שלשת ימים לתור להם מנוחה׃

כרובים, as a visual motif, had a number of forms:

ואת המשכן תעשה עשר יריעת; שש משזר ותכלת וארגמן ותלעת שני כרבים מעשה חשב תעשה אתם׃

כרבים מעשה חשב: כְּרוּבִים הָיוּ מְצֻיָּרִין בָּהֶם בַּאֲרִיגָתָן, וְלֹא בִרְקִימָה שֶׁהוּא מַעֲשֵׂה מַחַט, אֶלָּא בַאֲרִיגָה בִשְׁנֵי כְּתָלִים, פַּרְצוּף אֶחָד מִכָּאן וּפַרְצוּף אֶחָד מִכָּאן—אֲרִי מִצַּד זֶה וְנֶשֶׁר מִצַּד זֶה…

והיו הכרובים: כבר בארו הנביאים שהמלאכים במראה הנבואה נראים לחוזים כדמות כרובים, והם פני אדם ולהם כנפים. ובכל זה יורו ענין השכל הנבדל אשר כל הלוכו לצד מעלה, וזה להביט אל האלקים השכל וידוע אותו כל אחד מהשכלים הנבדלים כפי האפשר אצלו.

And that is what ירבעם built:

אין ספק שהראה במעשה זה פנים לכל צד, אל יראי ה׳ אמר שעשאם לשם הא־ל שכמו שישכון במקדש על שני הכרובים הלקוחים מהמרכבה שהיא צורה אנושית מורה על החכמה, השיא אותם שישכון בבית אל ובדן אל פני שור שבמרכבה שמורה על ריבוי התבואות וכח שור.

I would argue that if you were looking at them, you would not be able to tell the difference between a כרוב and an עגל. The two terms are an editorial choice. Statues of כרובים are are commanded by ה׳; statues of עגלים are not.

יח ויאמר ה׳ אל משה כה תאמר אל בני ישראל; אתם ראיתם כי מן השמים דברתי עמכם׃

יט לא תעשון אתי; אלהי כסף ואלהי זהב לא תעשו לכם׃

לא תעשון אתי: לא תעשון דמות שמשי המשמשים לפני במרום.

אלהי כסף: בא להזהיר על הכרובים, שאתה עושה לעמוד אתי, שלא יהיו של כסף, שאם שניתם לעשותם של כסף הרי הן לפני כאלהות.

ואלהי זהב: בא להזהיר שלא יוסיף על שנים, שאם עשית ארבעה, הרי הן לפני כאלהי זהב.

לא תעשו לכם: לא תאמר הריני עושה כרובים בבתי כנסיות ובבתי מדרשות כדרך שאני עושה בבית עולמים, לכך נאמר לא תעשו לכם.

But even if they are not meant to be images of ה׳, they clearly end up that way in the eyes of the Babylonians etc., and in the eyes of בני ישראל themselves:

ויקח מידם ויצר אתו בחרט ויעשהו עגל מסכה; ויאמרו אלה אלהיך ישראל אשר העלוך מארץ מצרים׃

So why have these dangerous images? I think that it is because they fundamentally do not represent ה׳; they carry the merkava. They represent us. It’s important that we know that we as human beings have a role in “carrying” the שכינה in the world. We have a place in the קודש הקודשים:

כשבאו אל הר סיני ועשו המשכן ושב הקדוש ברוך הוא והשרה שכינתו ביניהם אז שבו אל מעלת אבותם, שהיה סוד א־לוה עלי אהליהם, והם הם המרכבה (ב״ר מז ח), ואז נחשבו גאולים ולכן נשלם הספר הזה בהשלימו ענין המשכן ובהיות כבוד ה׳ מלא אותו תמיד.