This shiur is similar to last year’s, פרשת כי תשא תשפ״ג, but with a different twist.

As part of the last paragraphs of instructions for the משכן, ה׳ tells Moshe to hire a general contractor:

א וידבר ה׳ אל משה לאמר׃ ב ראה קראתי בשם בצלאל בן אורי בן חור למטה יהודה׃ ג ואמלא אתו רוח אלקים בחכמה ובתבונה ובדעת ובכל מלאכה׃ ד לחשב מחשבת; לעשות בזהב ובכסף ובנחשת׃

Who is this Betzalel? It’s interesting because he is identified not just by patronymic and tribe but by avonymic—the name of his grandfather. And Chur we have seen before, as one of the leaders of בני ישראל:

ויעש יהושע כאשר אמר לו משה להלחם בעמלק; ומשה אהרן וחור עלו ראש הגבעה׃

ואל הזקנים אמר שבו לנו בזה עד אשר נשוב אליכם; והנה אהרן וחור עמכם מי בעל דברים יגש אלהם׃

But Chur has no introduction, and no family history. Rashi gives us a hint:

חור: בנה של מרים היה וכלב בעלה.

So Betzalel is Miriam’s great-grandson. If Miriam is now 86 years old, then Betzalel must be a pretty young man (if all the generations are equal, then he is about 21). But the gemara goes further. דברי הימים tells us of Betzalel’s yichus:

ג בני יהודה ער ואונן ושלה שלושה נולד לו מבת שוע הכנענית; ויהי ער בכור יהודה רע בעיני ה׳ וימיתהו׃ ד ותמר כלתו ילדה לו את פרץ ואת זרח; כל בני יהודה חמשה׃ ה בני פרץ חצרון וחמול׃…ט ובני חצרון אשר נולד לו את ירחמאל ואת רם ואת כלובי׃…יח וכלב בן חצרון הוליד את עזובה אשה ואת יריעות; ואלה בניה ישר ושובב וארדון׃ יט ותמת עזובה; ויקח לו כלב את אפרת ותלד לו את חור׃ כ וחור הוליד את אורי ואורי הוליד את בצלאל׃

Now, the genealogies in דברי הימים are complicated and generally incomprehensible, and the gemara concludes:

רבי סימון בשם רבי יהושע בן לוי ורבי חמא אבוה דרבי הושעיא בשם רב אמרי: לא נתן דברי הימים אלא לדרש.

And so we will be focusing on the דרש of these psukim. Kalev is Betzalel’s great-grandfather (Efrat is identified with Miriam, as we will see), which doesn’t tell us anything. But there is another, better known, Kalev: כלב בן יפנה, one of the spies that were sent to spy out the land. And we know something about him:

ו ויגשו בני יהודה אל יהושע בגלגל ויאמר אליו כלב בן יפנה הקנזי; אתה ידעת את הדבר אשר דבר ה׳ אל משה איש האלקים על אדותי ועל אדותיך בקדש ברנע׃ ז בן ארבעים שנה אנכי בשלח משה עבד ה׳ אתי מקדש ברנע לרגל את הארץ; ואשב אתו דבר כאשר עם לבבי׃

And the gemara identifies the two. So Kalev is 40 years old in the year after the משכן is built, and it is built by his great-grandson.

וכי עבד בצלאל משכן בר כמה הוי בר תליסר דכתיב (שמות לו:ד) אִישׁ אִישׁ מִמְּלַאכְתּוֹ אֲשֶׁר הֵמָּה עֹשִׂים…כמה הויא להו [לכלב]? ארבעין. דל ארביסר דהוה בצלאל; פשא להו עשרים ושית. דל תרתי שני דתלתא עיבורי; אשתכח דכל חד וחד בתמני אוליד.

And the gemara identifies the wives of Kalev—all three of them—with Miriam:

״עזובה״ זו מרים, ולמה נקרא שמה עזובה? שהכל עזבוה מתחילתה…״יריעות״ — שהיו פניה דומין ליריעות.

ותמת עזובה אשת כלב: והיא מרים ולקמן מפרש למה נקראת שמה עזובה והאי ”ותמת“ שנצטרעה.

עזובה שהכל עזבוה: שמתחילה חולנית היתה כדקרי לה הכא יריעות ולקמן קרי לה נמי חלאה ועזובה שעזבוה כל בחורי ישראל מלישא אותה.

ויקח לו כלב את אפרת: לאחר שנתרפאת חזר ולקחה לו, אלמא אפרת קרי מרים וכתיב בדוד ”בן איש אפרתי“.

You can read Rabbi Eisemann’s commentary on דברי הימים for more on the aggadic approach to these geneaologies. But I want to note that Miriam is presented as one who was sickly, considered dead, and then is rejuvenated and gave birth to the line that would lead to Betzalel. And her mother, Yocheved, has a similar aggadah:

(שמות ב:א) אֶת בַּת לֵוִי: אפשר בת מאה ושלשים שנה היתה וקרי לה בת?…אמר רבי יהודה בן רבי זבינא שנולדו בה סימני נערות.

Taking all this seriously but not literally, I want to focus on the fact that the midrashic emphasis is on Betzalel’s ancestry being little children or rejuvenated adults.

And that connects to the main story of this week’s parsha: חטא עגל הזהב. We have talked many times about the meaning of the golden calf, as a representation of the כרובים that carry the מרכבה.

ודמות פניהם פני אדם ופני אריה אל הימין לארבעתם ופני שור מהשמאול לארבעתן; ופני נשר לארבעתן׃

But the golden calf isn’t a שור, an ox. It’s a baby ox. The people were trying to create their own version of the כרובים of the משכן.

כרבים: דמות פרצוף תינוק להם.

The contractor of the משכן is a baby, his ancestors were babies, the centerpiece of the משכן is a pair of babies. There is an emphasis on neoteny in the משכן.

neoteny

The retention of juvenile characteristics in the adult.

For instance, dogs were bred from wolves by selecting the most puppy-like animals.

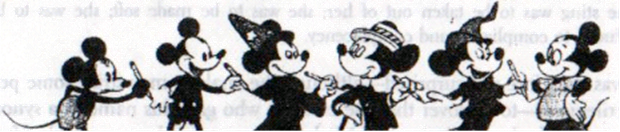

And Steven Jay Gould, the evolutionary biologist, had a famous article in 1979 about a famous example of neoteny in popular culture:

In the משכן, the heavenly כרובים become baby כרובים; that is an example of neoteny, and it serves as a physical symbol of natality.

The cherubim do not represent G-d or angels, but us. We look at them looking at the scene and identify with them, or should identify with them. They summon us to have a child-like wonder, to be naifs, beginners. Why is this important? Why is it important to have at the center of the Temple, at the boundary between the human and the transcendent?

…Hannah Arendt describes natality, newness, as the primary phenomenon that can liberate us from the oppression of systematic thinking. I see the cherubim as figures of natality.

natality

The human ability to create new ideas, institutions and frameworks.

Arendt…stresses the fact that…natality, since it is the actualization of freedom,…carries with it the capacity to…introduce what is totally unexpected. “It is in the nature of beginning”—she claims—“that something new is started which cannot be expected from whatever may have happened before. This character of startling unexpectedness is inherent in all beginnings…The fact that man is capable of action means that the unexpected can be expected from him, that he is able to perform what is infinitely improbable. And this again is possible only because each man is unique, so that with each birth something uniquely new comes into the world”. (The Human Condition, pp. 177–8).

She applies the idea in political philosophy in the history of revolutions, that start out with such potential for change but quickly stagnate into the same despotism they proported to rebel against, as they lose that natality. The obvious example is the rebellion against the Galactic Empire in Star Wars and the foundation of the Second Republic, which, in less than twenty years, becomes the First Order. Leia finds herself leading yet another “Resistance”, recapitualing the first movies.

But the cherubim are there to remind us not of our excellence, but of our constant need to begin again. It is a privilege to remain a beginner…

Our עבודת ה׳ must always have that sense of re-discovery, rebirth.

כה אמר ה׳ צבא־ות אם בדרכי תלך ואם את משמרתי תשמר וגם אתה תדין את ביתי וגם תשמר את חצרי ונתתי לך מהלכים בין העמדים האלה׃

Human beings differ from angels in their ability to change, to grow and improve. Angels cannot change; they remain the same from the moment they come into existence until they expire. For this reason, the prophets…describe angels as Omedim, “standing”…Human beings [are] referred to as Holechim, “walking”, referring to their capacity to progress, to move forward, to grow, to work on their characters and become better.

We are preeminently learning animals, and our extended childhood permits the transference of culture by education. Many animals display flexibility and play in childhood but follow rigidly programmed patterns as adults. Lorenz writes…“The characteristic which is so vital for the human peculiarity of the true man—that of always remaining in a state of development—is quite certainly a gift which we owe to the neotenous nature of mankind”.

In short, we, like Mickey, never grow up although we, alas, do grow old.

We say this in the שיר של יום for Monday:

כי זה אלקים אלקינו עולם ועד; הוא ינהגנו עלמות׃

Read הוא ינהגנו עלמות as, “Hashem will guide us through our natality”.

Betzalel in the eyes of the aggadah is a child, the descendant of children. The builder of the משכן must express neoteny, retain his natality, because completing the משכן is not the end. It is only the beginning of our spiritual growth.