Getting back to the rebellion of שבע בן בכרי, David wants to nip it in the bud.

ד ויאמר המלך אל עמשא הזעק לי את איש יהודה שלשת ימים; ואתה פה עמד׃ ה וילך עמשא להזעיק את יהודה; וייחר (ויוחר) מן המועד אשר יעדו׃

ו ויאמר דוד אל אבישי עתה ירע לנו שבע בן בכרי מן אבשלום; אתה קח את עבדי אדניך ורדף אחריו פן מצא לו ערים בצרות והציל עיננו׃ ז ויצאו אחריו אנשי יואב והכרתי והפלתי וכל הגברים; ויצאו מירושלם לרדף אחרי שבע בן בכרי׃

To review the characters here, David had two older sisters, צְרוּיָה and אֲבִיגָיִל. צְרוּיָה‘s sons were אַבְשַׁי, וְיוֹאָב and עֲשָׂהאֵל; and אֲבִיגָיִל’s son was עֲמָשָׂא (see דברי הימים א פרק ב). All of them served as David’s military leaders, with Yoav as his chief of staff. Asahel was killed during the David/Ish Boshet civil war, when he chased after Avner, Saul’s general. Avner begged him to stop, then killed him in self-defense. Amasa joined Avshalom in his rebellion, but after Yoav killed Avshalom and rebuked David, David fired Yoav and hired Amasa in his place:

ולעמשא תמרו הלוא עצמי ובשרי אתה; כה יעשה לי אלקים וכה יוסיף אם לא שר צבא תהיה לפני כל הימים תחת יואב׃

This explains why David is addressing Amasa and Avishai here, not Yoav. But we need to remember that the army is fiercely loyal to Yoav; part of the force that goes with Avishai is אנשי יואב. Back in פרק יא, Uriah called Yoav (not David) אדני:

ויאמר אוריה אל דוד הארון וישראל ויהודה ישבים בסכות ואדני יואב ועבדי אדני על פני השדה חנים ואני אבוא אל ביתי לאכל ולשתות ולשכב עם אשתי; חיך וחי נפשך אם אעשה את הדבר הזה׃

When Avishai and his forces meet up with Amasa, Yoav goes to join them. And he does something odd:

הם עם האבן הגדולה אשר בגבעון ועמשא בא לפניהם; ויואב חגור מדו לבשו ועלו חגור חרב מצמדת על מתניו בתערה והוא יצא ותפל׃

תפל is feminine; it refers to the חרב (which is feminine; (במדבר כב:כג) וְחַרְבּוֹ שְׁלוּפָה בְּיָדוֹ). Yoav is a seasoned warrior, with his sword in its scabbard fixed to his thigh, and yet his sword just happens to fall out.

והוא יצא: מהאבן הנזכר, ונפלה מתערה בשחיה מועטת, אשר שחה לתקן מנעלו…ולקחה מהארץ בשמאלו.

It’s not an accident. Yoav picks up his sword in his left hand and goes to greet Amasa in apparent friendliness:

ט ויאמר יואב לעמשא השלום אתה אחי; ותחז יד ימין יואב בזקן עמשא לנשק לו׃ י ועמשא לא נשמר בחרב אשר ביד יואב ויכהו בה אל החמש וישפך מעיו ארצה ולא שנה לו וימת; ויואב ואבישי אחיו רדף אחרי שבע בן בכרי׃

This is entirely in character for Yoav. He holds grudges, and really likes how that fifth rib solves problems:

ו ויהי בהיות המלחמה בין בית שאול ובין בית דוד; ואבנר היה מתחזק בבית שאול׃

…יב וישלח אבנר מלאכים אל דוד תחתו לאמר למי ארץ; לאמר כרתה בריתך אתי והנה ידי עמך להסב אליך את כל ישראל׃

…כא ויאמר אבנר אל דוד אקומה ואלכה ואקבצה אל אדני המלך את כל ישראל ויכרתו אתך ברית ומלכת בכל אשר תאוה נפשך; וישלח דוד את אבנר וילך בשלום׃ כב והנה עבדי דוד ויואב בא מהגדוד ושלל רב עמם הביאו; ואבנר איננו עם דוד בחברון כי שלחו וילך בשלום׃ כג ויואב וכל הצבא אשר אתו באו; ויגדו ליואב לאמר בא אבנר בן נר אל המלך וישלחהו וילך בשלום׃ כד ויבא יואב אל המלך ויאמר מה עשיתה; הנה בא אבנר אליך למה זה שלחתו וילך הלוך׃ כה ידעת את אבנר בן נר כי לפתתך בא; ולדעת את מוצאך ואת מבואך ולדעת את כל אשר אתה עשה׃ כו ויצא יואב מעם דוד וישלח מלאכים אחרי אבנר וישבו אתו מבור הסרה; ודוד לא ידע׃ כז וישב אבנר חברון ויטהו יואב אל תוך השער לדבר אתו בשלי; ויכהו שם החמש וימת בדם עשהאל אחיו׃

And David will recognize the danger that Yoav represents:

ה וגם אתה ידעת את אשר עשה לי יואב בן צרויה אשר עשה לשני שרי צבאות ישראל לאבנר בן נר ולעמשא בן יתר ויהרגם וישם דמי מלחמה בשלם; ויתן דמי מלחמה בחגרתו אשר במתניו ובנעלו אשר ברגליו׃ ו ועשית כחכמתך; ולא תורד שיבתו בשלם שאל׃

But we need to realize that Yoav is never, in his own mind, betraying David. He is always loyal to David, and does what he thinks David needs, even if David doesn’t see it. That’s his justification for killing Avner, and his justification for killing Amasa: Amasa was clearly not competent to be David’s chief of staff (he failed this critical mission of mustering the army in 3 days) and only he (Yoav) could save the country. So they press on, now with Yoav in the lead (יואב ואבישי אחיו רדף אחרי שבע).

[אמר שלומה ליואב] מאי טעמא קטלתיה לעמשא? אמר ליה: עמשא מורד במלכות הוה דכתיב (שמואל ב כ:ד) ויאמר המלך לעמשא הזעק לי את איש יהודה שלשת ימים וגו׳ וילך עמשא להזעיק את יהודה ויוחר וגו׳.

Even though we only see the negative side of Yoav, the gemara notes how well he served David and the people:

דאמר רבי אבא בר כהנא אילמלא דוד לא עשה יואב מלחמה ואילמלא יואב לא עסק דוד בתורה דכתיב (שמואל ב ח:טו-טז) וַיְהִי דָוִד עֹשֶׂה מִשְׁפָּט וּצְדָקָה לְכָל עַמּוֹ׃ וְיוֹאָב בֶּן צְרוּיָה עַל הַצָּבָא. מה טעם דוד עשה משפט וצדקה לכל עמו משום דיואב על הצבא ומה טעם יואב על הצבא משום דדוד עושה משפט וצדקה לכל עמו.

(מלכים א ב:לד) וַיִּקָּבֵר [יוֹאָב] בְּבֵיתוֹ, בַּמִּדְבָּר. אטו ביתו מדבר הוא? אמר רב יהודה אמר רב: כמדבר. מה מדבר מופקר לכל, אף ביתו של יואב מופקר לכל. דבר אחר: כמדבר; מה מדבר מנוקה מגזל ועריות אף ביתו של יואב מנוקה מגזל ועריות. (דברי הימים א יא:ח) […קָרְאוּ לוֹ עִיר דָּוִיד…] וְיוֹאָב יְחַיֶּה אֶת שְׁאָר הָעִיר; אמר רב יהודה: אפילו מוניני וצחנתא טעים פריס להו.

And now the loyalty of the army to Yoav comes to the fore:

יא ואיש עמד עליו מנערי יואב; ויאמר מי אשר חפץ ביואב ומי אשר לדוד אחרי יואב׃ יב ועמשא מתגלל בדם בתוך המסלה; וירא האיש כי עמד כל העם ויסב את עמשא מן המסלה השדה וישלך עליו בגד כאשר ראה כל הבא עליו ועמד׃ יג כאשר הגה מן המסלה עבר כל איש אחרי יואב לרדף אחרי שבע בן בכרי׃

Yoav is now effectively the general of David’s army despite David’s command. And David will accede to Yoav’s return; at the end of the perek it says:

ויואב אל כל הצבא ישראל; ובניה בן יהוידע על הכרתי ועל הפלתי׃

And we return to the rebellion:

ויעבר בכל שבטי ישראל אבלה ובית מעכה וכל הברים;

ויקלהו (ויקהלו) ויבאו אף אחריו׃

It’s unclear who the subject of this pasuk is, but I will assume with Abarbanel that this is the story of שבע בן בכרי:

ויעבור בכל שבטי ישראל: ספר הכתוב ששבע בן בכרי (שאמר ממנו בסמוך לרדוף אחרי שבע בן בכרי) הוא עבר בכל ישראל לפתותם ולדבר על לבם כנגד דוד, ועבר עד אבלה שהוא בלי סַפֵּר העיר אשר בא שמה. ואמרו עוד ובית מעכה וכל הברים הוא דבק למטה, יאמר ששבע בן בכרי עבר בכל שבטי ישראל והלך אבלה ושבית מעכה וכל הברים נקהלו ויבאו אף אחריו עד אבלה אשר נשגב שמה.

שבע has been on the run בכל שבטי ישראל and ends up in the city of אָבֵלָה (a little bit of foreshadowing, hiding in a city named “mourning”) in the area of בית מעכה and the ברים. Unfortunately, that doesn’t tell us anything:

וכל הברים: לא ידעתי מהו.

But most commentators assume that it is in the area of בנימן (which makes sense, since שבע בן בכרי is from בנימן):

וכל הברים ויקהלו ויבאו אף אחריו: וכל הברים אחשוב שהם אנשי בארות כי בארות היה מבנימן.

כא והיו הערים למטה בני בנימן למשפחותיהם; יריחו ובית חגלה ועמק קציץ׃…כה גבעון והרמה ובארות׃

What’s interesting about בארות is that it was a major city of the גבעונים, one of the Canaanite nations:

ג וישבי גבעון שמעו את אשר עשה יהושע ליריחו ולעי׃ ד ויעשו גם המה בערמה וילכו ויצטירו; ויקחו שקים בלים לחמוריהם ונאדות יין בלים ומבקעים ומצררים׃…טו ויעש להם יהושע שלום ויכרת להם ברית לחיותם; וישבעו להם נשיאי העדה׃…יז ויסעו בני ישראל ויבאו אל עריהם ביום השלישי; ועריהם גבעון והכפירה ובארות וקרית יערים׃

And it is possible that it was גבעונים who assassinated Ish Boshet (see Rabbi Shulman’s shiurim on שמואל ב פרק ד).

א וישמע בן שאול כי מת אבנר בחברון וירפו ידיו; וכל ישראל נבהלו׃ ב ושני אנשים שרי גדודים היו בן שאול שם האחד בענה ושם השני רכב בני רמון הבארתי מבני בנימן; כי גם בארות תחשב על בנימן׃ ג ויברחו הבארתים גתימה; ויהיו שם גרים עד היום הזה׃

…ה וילכו בני רמון הבארתי רכב ובענה ויבאו כחם היום אל בית איש בשת; והוא שכב את משכב הצהרים׃ ו והנה באו עד תוך הבית לקחי חטים ויכהו אל החמש; ורכב ובענה אחיו נמלטו׃…ח ויבאו את ראש איש בשת אל דוד חברון ויאמרו אל המלך הנה ראש איש בשת בן שאול איבך אשר בקש את נפשך; ויתן ה׳ לאדני המלך נקמות היום הזה משאול ומזרעו׃

The Givonim seem to be very involved in undermining Jewish sovereignty in Israel. We will have to look at this more when we get to the next perek.

So the Israelite forces arrive at אבלה but are stymied by the city wall:

ויבאו ויצרו עליו באבלה בית המעכה וישפכו סללה אל העיר ותעמד בחל; וכל העם אשר את יואב משחיתם להפיל החומה׃

This was exactly the situation that David was afraid of:

ויאמר דוד אל אבישי עתה ירע לנו שבע בן בכרי מן אבשלום; אתה קח את עבדי אדניך ורדף אחריו פן מצא לו ערים בצרות והציל עיננו׃

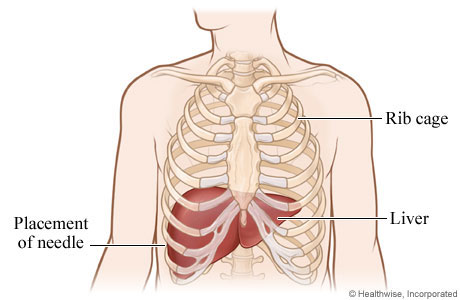

A side note about the חֵל: it refers to a low wall outside the main wall, and the empty, free-fire zone between them. It is an important security measure, analogous to a moat. There was a חֵל in the בית המקדש as well, not for security, but as a kind of warning track to keep non-Jews away from the Temple proper (labeled ד in the illustration).

(איכה ב:ח) וַיַּאֲבֶל חֵל וְחוֹמָה. וואמר רבי אחא ואיתימא רבי חנינא: שורא ובר שורא

The situation is very similar to פלגש בגבעה: the Benjaminites are harboring a fugitive and the Israelite army besieges the city, but the inhabitants refuse to give him up. That war ended very badly, nearly wiping out all of שבט בנימין. This battle will likely end up the same way, especially with Yoav in command. He’s massacred civilians before:

טו ויהי בהיות דוד את אדום בעלות יואב שר הצבא לקבר את החללים; ויך כל זכר באדום׃

טז כי ששת חדשים ישב שם יואב וכל ישראל עד הכרית כל זכר באדום׃

And the city is saved—and by extension, the country as a whole is saved from civil war—by an אשה חכמה:

טז ותקרא אשה חכמה מן העיר; שמעו שמעו אמרו נא אל יואב קרב עד הנה ואדברה אליך׃ יז ויקרב אליה ותאמר האשה האתה יואב ויאמר אני; ותאמר לו שמע דברי אמתך ויאמר שמע אנכי׃ יח ותאמר לאמר; דבר ידברו בראשנה לאמר שאול ישאלו באבל וכן התמו׃ יט אנכי שלמי אמוני ישראל; אתה מבקש להמית עיר ואם בישראל למה תבלע נחלת ה׳׃

The אשה חכמה points out that if Yoav had only started by talking rather than attacking, all this could be avoided:

שאול ישאלו באבל: אם שאלו בני חילך בשלום העיר הזאת.

וכן התמו: מיד היו בני העיר משלימים עמכם.

What does שְׁלֻמֵי אֱמוּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל mean?

אנכי שלומי אמוני ישראל. אני מבני העיר, ששלמים ונאמנים לישראל ולמלך.

But then Rashi brings an aggadah:

ומדרש אגדה (בראשית רבה צד ט, ובילקוט שמעוני כא): סרח בת אשר היתה, אני השלמתי נאמן לנאמן, על ידי נגלה ארונו של יוסף למשה, אני הגדתי ליעקב כי יוסף חי.

I dealt with this in פרשת ויגש תש״פ, and I’m going to quote it now:

The sources for this shiur came from Bracha Jaffe’s Serach Bat Asher—The Memory Keeper (Yahrtzeit Shiur) and Serach Bat Asher—More Sources and Cantor Arik Wollheim’s Hidden Women in Tanach: Serach. פרשת ויגש lists all of Yaakov’s descendants who go down to Egypt with him. The list includes only one girl:

ובני אשר ימנה וישוה וישוי ובריעה ושרח אחתם; ובני בריעה חבר ומלכיאל׃

It’s unlikely, but possible, that there was only one girl among the 70, but what’s remarkable is that she is also listed among those who returned to the land, 250 years later:

מד בני אשר למשפחתם לימנה משפחת הימנה לישוי משפחת הישוי; לבריעה משפחת הבריעי׃

מה לבני בריעה לחבר משפחת החברי; למלכיאל משפחת המלכיאלי׃

מו ושם בת אשר שרח׃

There are two possible approaches to understanding the role of שרח בת אשר: the Ramban looks at her from a פשט perspective, trying to understand why she is in the list of families that will settle the land. We will follow a דרש perspective, starting with Rashi:

ושם בת אשר שרח: לְפִי שֶׁהָיְתָה קַיֶּמֶת בְּחַיֶּיהָ מְנָאָהּ כָּאן.

Where does this come from, the idea that Serach lived for so long? It goes back to פרשת ויגש:

כה ויעלו ממצרים; ויבאו ארץ כנען אל יעקב אביהם׃

כו ויגדו לו לאמר עוד יוסף חי וכי הוא משל בכל ארץ מצרים; ויפג לבו כי לא האמין להם׃

כז וידברו אליו את כל דברי יוסף אשר דבר אלהם וירא את העגלות אשר שלח יוסף לשאת אתו; ותחי רוח יעקב אביהם׃

ויגדו לו: חסר יו״ד, לפי שהן בעצמם לא הגידו לו.

>

לאמר: לומר ע״י סרח בת אשר.

ויבואו עד גבול הארץ ויאמרו איש אל רעהו, מה נעשה בדבר הזה לפני אבינו? כי אם נבוא אליו פתאום ונגד לו הדבר ויבהל מאוד מדברינו, ולא יאבה לשמוע אלינו. וילכו להם עד קרבם אל בתיהם וימצאו את שרח בת אשר…ויתנו לה כינור אחד לאמור: בואי נא לפני אבינו וישבת לפניו, והך בכינור ודיברת ואמרת כדברים האלה לפניו…ותמהר ותלך לפניהם ותשב אצל יעקב. ותיטיב הכינור ותנגן ותאמר בנועם דבריה, יוסף דודי חי הוא וכי הוא מושל בכל ארץ מצרים ולא מת…וישמע יעקב את דבריה ויערב לו. וישמע עוד בדברה פעמיים ושלוש, ותבוא השמחה בלב יעקב מנועם דבריה ותהי עליו רוח אלוקים וידע כי כל דבריה נכונה. ויברך יעקב את שרח בדברה הדברים האלה לפניו ויאמר אליה, בתי אל ימשול מות בך עד עולם כי החיית את רוחי. אך דברי נא עוד לפניי כאשר דיברת, כי שמחתני בכל דברייך. ותוסף ותנגן כדברים האלה ויעקב שומע ויערב לו וישמח, ותהי עליו רוח אלוקים.

Now, the ספר הישר is an obscure midrashic collection (first published apparently in the 16th century, but it’s mentioned by the Ramban, but skeptically). However, Serach appears through history in more authoritative midrashic sources:

וישבע יוסף את בני ישראל לאמר; פקד יפקד אלקים אתכם והעלתם את עצמתי מזה׃

לך ואספת את זקני ישראל ואמרת אלהם ה׳ אלקי אבתיכם נראה אלי אלקי אברהם יצחק ויעקב לאמר; פקד פקדתי אתכם ואת העשוי לכם במצרים׃

ובמה האמינו על סימן הפקידה שאמר להם? שכך היה מסורת בידם מיעקב שיעקב מסר את הסוד ליוסף ויוסף לאחיו ואשר בן יעקב מסר את הסוד לסרח בתו ועדיין היתה היא קיימת. וכך אמר לה: כל גואל שיבא ויאמר לבני פקוד פקדתי אתכם הוא גואל של אמת. כיון שבא משה ואמר פקוד פקדתי אתכם מיד ויאמן העם, במה האמינו? כי שמעו הפקידה.

ומנין היה יודע משה רבינו היכן יוסף קבור? אמרו: סרח בת אשר נשתיירה מאותו הדור, הלך משה אצלה, אמר לה: כלום את יודעת היכן יוסף קבור? אמרה לו: ארון של מתכת עשו לו מצרים וקבעוהו בנילוס הנהר, כדי שיתברכו מימיו.

And going even further into the future to our story:

יֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים סֶרַח בַּת אָשֵׁר הִשְׁלִימָה עִמָּהֶן אֶת הַמִּנְיָן; הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב: וַתִּקְרָא אִשָּׁה חֲכָמָה מִן הָעִיר…וְאָמַר לָהּ מַאן אַתְּ, אָמְרָה לֵיהּ: אָנֹכִי שְׁלֻמֵי אֱמוּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, אֲנִי הוּא שֶׁהִשְׁלַמְתִּי מִנְיָינָן שֶׁל יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּמִצְרַיִם, אֲנִי הוּא שֶׁהִשְׁלַמְתִּי נֶאֱמָן לְנֶאֱמָן, יוֹסֵף לְמשֶׁה…מְבַקֵּשׁ לְהָמִית עִיר וְלִי שֶׁאֲנִי אֵם בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל.

Serach is the one אָשֵׁר הִשְׁלִימָה עִמָּהֶן אֶת הַמִּנְיָן; she is the one woman who completes the count of the שבעים נפש ירדו אבתיך מצרימה.

And she becomes the midrashic symbol of the אשה חכמה:

פיה פתחה בחכמה: זו אשה חכמה, שאמרה: שמעו שמעו אמרו נא אל יואב קרב עד הנה ואדברה אליך, שהצילה את העיר בחכמתה, וזו היתה סרח בת אשר.

ר׳ יוחנן הוה יתיב דרש כיצד היו המים עשויין לישרה כחומה. דרש ר׳ יוחנן כאילין קנקילייא [a net].

אדיקת שרח בת אשר ואמרת: תמן הוינא ולא הוון אלא כאילין אמפומטא [a window].

Her role, in all these midrashic stories, is to be the witness to the history of the Jewish people. She is the one who restored Yaakov’s future, so she is the one who remembers the past. Rav Soloveitchik saw this as a critical part of the מסורה:

אפילו בדורו של משה, בדור פלאים שיצא ממצרים, שראה מראות אלקים בסיני וקיבל את התורה, צריכים היו לדמות קדומה, סרח בת אשר, שבילדותה ישבה בחיקו של הסבא הזקן והשתעשעה

בשערות ראשו וזקנו.

בלעדיה הייתה נפסקת רציפת הדורות האישית…אי-אפשר לרנן זֶה אֵ־לִי וְאַנְוֵהוּ, אם אין שירת ההווה מוצמדת לשירת העבר—אֱ־לֹהֵי אָבִי וַאֲרֹמְמֶנְהוּ. רק אֵם זקנה, שחוחת גו וחרושת פנים, שהתחטאה לפני הזקן וקראה לו ”סבא“, יודעת את סוד חיבור הדורות וקישור הימים ההם עם הזמן הזה.

Why was it crucial that Serach play a role in the redemption? The generation of the exodus witnessed signs and wonders on an unprecedented scale. Such excitement could easily lead to a sense that their generation represents true religious greatness and that nothing that came beforehand really matters. Yet this conclusion is false. Every generation, irrespective of its accomplishments, needs to turn to its elders for counsel and wisdom. The living example of someone who knew Yaakov Avinu was an invaluable resource for the generation of redemption. For the same reason, the blessing in the Amida refers to “the remnants of the scribes’” (על פליטת סופריהם) rather than simple ‘the scribes.” We want not only wise individuals but also those with memories of previous generations.

שמע בני מוסר אביך ואל תטש תורת אמך׃

What is torat imekha? What kind of a Torah does the mother

pass on? I admit that I am not able to define precisely the massoretic role of the Jewish mother…I used to watch [my mother] arranging the house in honor of a holiday. I used to see her recite prayers; I used to watch her recite the sidra every Friday night and I still remember the nostalgic tune. I learned from her very much. Most of all I learned that Judaism expresses itself not only in formal compliance with the law but also in a living experience. She taught me that there is a flavor, a scent and warmth to mitzvot. I learned from her the most important thing in life—to feel the presence of the Almighty and the gentle pressure of His hand resting upon my frail shoulders. Without her teachings, which quite often were transmitted to me in silence, I would have grown up a soulless being, dry and insensitive.

There were two mesoros that Moses transferred to Joshua. One is the tradition of Torah learning, of lomdus. The second mesorah, the hod, was experiential. One can know the entire Maseches Shabbos and yet still not know what Shabbos is. To truly know what Shabbos is, one has to spend time in a Yiddishe home. Even in those neighborhoods made up predominantly of religious Jews, today one can no longer talk of the sanctity of Shabbos. True, there are Jews in America who observe Shabbos; but there are no “Erev Shabbos Jews”, who go out to greet Shabbos with beating hearts and pulsating souls.

And a way of life is not learned but rather absorbed. Its transmission is mimetic, imbibed from parents and friends, and patterned on conduct regularly observed in home and street, synagogue and school.

Did these mimetic norms—the culturally prescriptive—conform with the legal ones? The answer is, at times, yes; at times, no. And the significance of the no may best be brought home by an example with which all are familiar—the kosher kitchen, with its rigid separation of milk and meat—separate dishes, sinks, dish racks, towels, tablecloths, even separate cupboards. Actually little of this has a basis in Halakhah. Strictly speaking, there is no need for separate sinks, for separate dishtowels or cupboards. In fact, if the food is served cold, there is no need for separate dishware altogether. The simple fact is that the traditional Jewish kitchen, transmitted from mother to daughter over generations, has been immeasurably and unrecognizably amplified beyond all halakhic requirements. Its classic contours are the product not of legal exegesis, but of the housewife’s religious intuition imparted in kitchen apprenticeship.

…It is this rupture [the loss of the mimetic tradition] in the traditional religious sensibilities that underlies much of the transformation of contemporary Orthodoxy. Zealous to continue traditional Judaism unimpaired, religious Jews seek to ground their new emerging spirituality less on a now unattainable intimacy with Him, than on an intimacy with His Will, avidly eliciting Its intricate demands and saturating their daily lives with Its exactions. Having lost the touch of His presence, they seek now solace in the pressure of His yoke.

חז״ל say that Yaakov never died:

רבי יצחק אומר בשם רבי יוחנן: יעקב אבינו לא מת. אמר ליה: וכי בכדי ספדו ספדנייא וחנטו חנטייא וקברו קברייא?!

אמר ליה: מקרא אני דורש, שנאמר (ירמיהו ל:י): וְאַתָּה אַל תִּירָא עַבְדִּי יַעֲקֹב נְאֻם ה׳ וְאַל תֵּחַת יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי הִנְנִי מוֹשִׁיעֲךָ מֵרָחוֹק וְאֶת זַרְעֲךָ מֵאֶרֶץ שִׁבְיָם וְשָׁב יַעֲקֹב וְשָׁקַט וְשַׁאֲנַן וְאֵין מַחֲרִיד. מקיש הוא לזרעו: מה זרעו בחיים אף הוא בחיים.

And in exactly the same way, as long as we have those with a memory of the past, as long as the mimetic tradition is not completely ruptured, שרח בת אשר לא מת. Pace Haym Soloveitchik, we still feel the gentle pressure of His hand.

So in the eyes of חז״ל, the text of our perek is setting up a contrast between Yoav and Serach. The text does not have the details of the verbal battle between them, but the midrash fills in the narrative gaps:

טובה חכמה מכלי קרב; וחוטא אחד יאבד טובה הרבה׃

טובה חכמה, זו חכמתה של סרח בת אשר. מכלי קרב, של יואב…ותאמר האשה האתה יואב…לאו את בר תורה, לאו דוד בר תורה, לאו הכי כתיב, (דברים כ:י) כִּי תִקְרַב אֶל עִיר לְהִלָּחֵם עָלֶיהָ וְקָרָאתָ אֵלֶיהָ לְשָׁלוֹם?

In my mind the contrast is between two aspects of David’s personality, between a unity that is enforced by killing all those who differ, and a unity that emphasizes our common history and destiny. Serach is no pacifist (as we will see) but she does prevail, and the city of אבלה does not become a city of אבלות, and Israel will survive the end of ספר שמואל and be able to build the בית המקדש in ספר מלכים.

כ ויען יואב ויאמר; חלילה חלילה לי אם אבלע ואם אשחית׃ כא לא כן הדבר כי איש מהר אפרים שבע בן בכרי שמו נשא ידו במלך בדוד תנו אתו לבדו ואלכה מעל העיר; ותאמר האשה אל יואב הנה ראשו משלך אליך בעד החומה׃ כב ותבוא האשה אל כל העם בחכמתה ויכרתו את ראש שבע בן בכרי וישלכו אל יואב ויתקע בשפר ויפצו מעל העיר איש לאהליו; ויואב שב ירושלם אל המלך׃

At this point, I should deal with the halachic implications of this perek:

תני: סיעות בני אדם שהיו מהלכין בדרך; פגעו להן גוים ואמרו תנו לנו אחד מכם ונהרוג אותו, ואם לאו הרי אנו הורגים את כולכם. אפילו כולן נהרגים לא ימסרו נפש אחת מישראל. ייחדו להן אחד כגון שבע בן בכרי, ימסרו אותו ואל ייהרגו. א״ר שמעון בן לקיש: והוא שיהא חייב מיתה כשבע בן בכרי. ורבי יוחנן אמר אע״פ שאינו חייב מיתה כשבע בן בכרי.

But I’m not going to do that; for halachic questions, please contact your local orthodox rabbi. I will just point out that the comparison makes it clear that חז״ל felt that Yoav was acting like as a case of פגעו להן גוים. His was not a Jewish response.

And while the story ends with ויואב שב ירושלם אל המלך, seemingly with no repercussions, I think there was a long-term consequence of this battle. We quoted the midrash that associated it with a pasuk from קהלת, טובה חכמה מכלי קרב. Let’s look at the context of that quote:

יג גם זה ראיתי חכמה תחת השמש; וגדולה היא אלי׃ יד עיר קטנה ואנשים בה מעט; ובא אליה מלך גדול וסבב אתה ובנה עליה מצודים גדלים׃ טו ומצא בה איש מסכן חכם ומלט הוא את העיר בחכמתו; ואדם לא זכר את האיש המסכן ההוא׃ טז ואמרתי אני טובה חכמה מגבורה; וחכמת המסכן בזויה ודבריו אינם נשמעים׃ יז דברי חכמים בנחת נשמעים מזעקת מושל בכסילים׃ יח טובה חכמה מכלי קרב; וחוטא אחד יאבד טובה הרבה׃

That story certainly sounds familiar!

הקרוב ביותר לזיהוי הוא מעשה אבל בית מעכה, שגם עליו נדרש שם הפסוק: טובה חכמה מכלי קרב, אכן במידה רבה נותן פסוקנו להתפרש על ידי המאורע ההוא.

At the time of our story, Shlomo is 8 years old. Four years from now, he will be king of Israel and he asks ה׳ for only one thing:

ד:ה בגבעון נראה ה׳ אל שלמה בחלום הלילה; ויאמר אלקים שאל מה אתן לך׃…ד:ט ונתת לעבדך לב שמע לשפט את עמך להבין בין טוב לרע; כי מי יוכל לשפט את עמך הכבד הזה׃

…ה:ט ויתן אלקים חכמה לשלמה ותבונה הרבה מאד; ורחב לב כחול אשר על שפת הים׃

When did he learn the value of wisdom; ראיתי חכמה תחת השמש; וגדולה היא אלי? It would seem it was from learning about the rebellion of שבע בן בכרי and its aftermath, and the nature of תורת אמך and the ongoing presence of סרח בת אשר.

י אשת חיל מי ימצא; ורחק מפנינים מכרה׃ כו…פיה פתחה בחכמה; ותורת חסד על לשונה׃

פיה פתחה בחכמה: זו אשה חכמה, שאמרה: ”שמעו שמעו אמרו נא אל יואב קרב עד הנה ואדברה אליך“, שהצילה את העיר בחכמתה, וזו היתה סרח בת אשר.

The פרק תהילים I want to look at is another one that deals with David facing his enemies. The Malbim says the parallelism represents two kinds of enemies:

א למנצח מזמור לדוד׃

ב חלצני ה׳ מאדם רע; מאיש חמסים תנצרני׃

יש שני מיני רודפים, א] המבקשים רק להרע מבלי תועלת עצמם, והם שהלשינו עליו בסתר, והמאמרים מקבילים, חלצני ה׳ מאדם רע אשר חשבו רעות בלב, ב] המבקשים לחמסו מצד הנאת עצמם, והם לחמו אתו בגלוי, ועז״א מאיש חמסים תנצרני (אשר) כל יום יגורו מלחמות

I’m going to look at this a little differently. David needs protection from two kinds of people: his enemies, and his friends whose help does more harm than good. I would propose that Yoav is the איש חמסים. He is not an אדם רע; he never intends evil.

“Violence,” came the retort, “is the last refuge of the incompetent.”

ג אשר חשבו רעות בלב; כל יום יגורו מלחמות׃

ד שננו לשונם כמו נחש; חמת עכשוב תחת שפתימו סלה׃

Again, there is a difference between the ones who חשבו רעות and those who יגורו מלחמות.

David needs to be saved from both his enemies and his friends.

The man of knowledge must be able not only to love his enemies but also to hate his friends.

It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends.

The second stich goes from two-fold parallelism to three fold, adding a line that summarizes both sides.

ה שמרני ה׳ מידי רשע מאיש חמסים תנצרני;

אשר חשבו לדחות פעמי׃

ו טמנו גאים פח לי וחבלים פרשו רשת ליד מעגל;

מקשים שתו לי סלה׃

אשר חשבו doesn’t necessarily mean “planned to”; it means “was about to”, something that threatens to happen:

וה׳ הטיל רוח גדולה אל הים ויהי סער גדול בים; והאניה חשבה להשבר׃

Both set traps, even the one who uses violence ostensibly for my benefit (פרשו רשת ליד מעגל, not לי but in general). They are מקשים שתו לי, snares set for me.

ז אמרתי לה׳ א־לי אתה; האזינה ה׳ קול תחנוני׃

ח ה׳ אדנ־י עז ישועתי; סכתה לראשי ביום נשק׃

ט אל תתן ה׳ מאויי רשע; זממו אל תפק ירומו סלה׃

But the next stich seems to prove me wrong. David asks that his enemies be punished harshly:

י ראש מסבי עמל שפתימו יכסומו (יכסימו)׃

יא ימיטו (ימוטו) עליהם גחלים; באש יפלם; במהמרות בל יקומו׃

יב איש לשון בל יכון בארץ; איש חמס רע יצודנו למדחפת׃

10 As for the head of those who compass me about, let the mischief of their own lips cover them.

11 Let burning coals fall upon them: let them be cast into the fire; into deep pits, so that they do not rise up again.

12 Let not a slanderer be established in the earth: let evil hunt the violent man to his overthrow.

ראש מסיבי: זה הרשע שהוא ראש הסובבים לי ללוכדני עמל שפתימו יכסמו השקר שמדבר עלי הוא וחביריו השקר ההוא יכסה אותם ויפילם.

ימוטו: ינטו גחלים מן השמים עליהם כלומר אף ה׳ וחמתו באש יפילם, עמל שפתימו שזכר.

במהמרות: בשוחות עמוקות יפילם שלא יקומו מהם.

איש חמס רע יצודנו למדחפות הרע שהוא עושה יצוד אותו עד שיטילנו למדחפות שיהיה נדחף מרעה אל רעה.

This all seems far too cruel for the David portrayed in ספר תהילים, and certainly if we are interpreting this perek in terms of not enemies but friends who love violence. Alshich has a more positive interpretation of פסוק י:

אך בה׳ בטחנו כי ”ראש מסבי“ היא התורה שהיא ראש המסבבים אותי להצילני, שהוא עמל שפתימו שעמלים העוסקים בה בשפתותיהם יעמלו בה, ויעשה העמל ההוא לנו כסוי ומגן.

And the ימוטו עליהם גחלים? It should remind us of something. It’s more explicit in תהילים יח:

ט עָלָה עָשָׁן בְּאַפּוֹ וְאֵשׁ מִפִּיו תֹּאכֵל;

גֶּחָלִים בָּעֲרוּ מִמֶּנּוּ׃…יג מִנֹּגַהּ נֶגְדּוֹ; עָבָיו עָבְרוּ בָּרָד וְגַחֲלֵי אֵשׁ׃

יד וַיַּרְעֵם בַּשָּׁמַיִם ה׳ וְעֶלְיוֹן יִתֵּן קֹלוֹ; בָּרָד וְגַחֲלֵי אֵשׁ׃

What is it about ברד?

יג ויאמר ה׳ אל משה השכם בבקר והתיצב לפני פרעה; ואמרת אליו כה אמר ה׳ אלקי העברים שלח את עמי ויעבדני׃ יד כי בפעם הזאת אני שלח את כל מגפתי אל לבך ובעבדיך ובעמך בעבור תדע כי אין כמני בכל הארץ׃ טו כי עתה שלחתי את ידי ואך אותך ואת עמך בדבר; ותכחד מן הארץ׃ טז ואולם בעבור זאת העמדתיך בעבור הראתך את כחי; ולמען ספר שמי בכל הארץ׃ יז עודך מסתולל בעמי לבלתי שלחם׃ יח הנני ממטיר כעת מחר ברד כבד מאד אשר לא היה כמהו במצרים למן היום הוסדה ועד עתה׃ יט ועתה שלח העז את מקנך ואת כל אשר לך בשדה; כל האדם והבהמה אשר ימצא בשדה ולא יאסף הביתה וירד עלהם הברד ומתו׃ כ הירא את דבר ה׳ מעבדי פרעה הניס את עבדיו ואת מקנהו אל הבתים׃ כא ואשר לא שם לבו אל דבר ה׳ ויעזב את עבדיו ואת מקנהו בשדה׃

כב ויאמר ה׳ אל משה נטה את ידך על השמים ויהי ברד בכל ארץ מצרים; על האדם ועל הבהמה ועל כל עשב השדה בארץ מצרים׃ כג ויט משה את מטהו על השמים וה׳ נתן קלת וברד ותהלך אש ארצה; וימטר ה׳ ברד על ארץ מצרים׃ כד ויהי ברד ואש מתלקחת בתוך הברד; כבד מאד אשר לא היה כמהו בכל ארץ מצרים מאז היתה לגוי׃…כז וישלח פרעה ויקרא למשה ולאהרן ויאמר אלהם חטאתי הפעם; ה׳ הצדיק ואני ועמי הרשעים׃…לג ויצא משה מעם פרעה את העיר ויפרש כפיו אל ה׳; ויחדלו הקלות והברד ומטר לא נתך ארצה׃ לד וירא פרעה כי חדל המטר והברד והקלת ויסף לחטא; ויכבד לבו הוא ועבדיו׃ לה ויחזק לב פרעה ולא שלח את בני ישראל; כאשר דבר ה׳ ביד משה׃

א ויאמר ה׳ אל משה בא אל פרעה; כי אני הכבדתי את לבו ואת לב עבדיו למען שתי אתתי אלה בקרבו׃ ב ולמען תספר באזני בנך ובן בנך את אשר התעללתי במצרים ואת אתתי אשר שמתי בם; וידעתם כי אני ה׳׃

בפעם הזאת אני שלח את כל מגפתי means that this plague is the last one aimed at Pharaoh and the Egyptians. After this, ה׳ says הכבדתי את לבו ואת לב עבדיו; they no longer has the free will to decide what to do. They have turned from human beings to Nonplayer Characters. The nature of the מכות is that the overt revelation of Divine power makes free will impossible; we see the same thing at מעמד הר סיני:

(שמות יט:יז) וַיִּתְיַצְּבוּ בְּתַחְתִּית הָהָר. א״ר אבדימי בר חמא בר חסא: מלמד שכפה הקב״ה עליהם את ההר כגיגית ואמר להם אם אתם מקבלים התורה מוטב ואם לאו שם תהא קבורתכם.

שהראה להם כבוד ה‘ בהקיץ ובהתגלות נפלאה, עד כי ממש בטלה בחירתם הטבעי…וראו כי כל הנבראים תלוי רק בקבלת התורה.

מכת ברד was the tipping point of the מכות. It represented just enough revelation, just enough miraculous phenomena, that it was possible to attribute it all to natural causes and deny Providence, if they really wanted to. Rav Dessler talks about the נקודת הבחירה:

כל אדם יש לו בחירה, היינו בנקודת פגישת האמת שלו עם האמת המדומה, תולדת השקר. אבל רוב מעשיו הם במקום שאין האמת והשקר נפגשים שם כלל. כי יש הרבה מן האמת שהאדם מחונך לעשותו, ולא יעלה על דעתו כלל לעשות ההיפך, וכן הרבה אשר יעשה מן הרע והשקר, שלא יבחין כלל שאין ראוי לעשותו. אין הבחירה שייכת אלא בנקודה שבין צבאו של היצה״ט לצבאו של היצה״ר.

…אמנם נקודה זו של הבחירה אינה עומדת תמיד על מצב אחד, כי בבחירות הטובות האדם עולה למעלה, היינו שהמקומות שהיו מערכת המלחמה מקודם, נכנסים לרשות היצה״ט, ואז המעשים הטובים שיוסיף לעשות בהם יהיה בלי שום מלחמה ובחירה כלל, וזהו ”מצוה גוררת מצוה“; וכן להיפך, הבחירות הרעות מגרשות היצה״ט ממקומו, וכשיוסיף לעשות מן הרע ההוא יעשנו בלי בחירה, כי אין עוד אחיזה ליצה״ט במקום ההוא. וזהו אז״ל ”עבירה גוררת עבירה“.

…היוצא מדברינו, שאין בחירה אלא בנקודת הבחירה…

So ברד represents not only a punishment, but a test as well. David, in asking ימוטו עליהם גחלים, is asking ה׳ to bring them to their נקודת הבחירה, force them to make the moral choices that will determine their fate.

And the conclusion is, of course, גם זו לטובה. It will work out in the end.

יג ידעת (ידעתי) כי יעשה ה׳ דין עני; משפט אבינים׃

יד אך צדיקים יודו לשמך; ישבו ישרים את פניך׃