After David gives the plans for the בית המקדש to Shlomo, he turns to the people.

ויאמר דויד המלך לכל הקהל שלמה בני אחד בחר בו אלקים נער ורך; והמלאכה גדולה כי לא לאדם הבירה כי לה׳ אלקים׃

The word בירה appears only in the post-exilic books of תנ״ך:

ב בימים ההם כשבת המלך אחשורוש על כסא מלכותו אשר בשושן הבירה׃ ג בשנת שלוש למלכו עשה משתה לכל שריו ועבדיו; חיל פרס ומדי הפרתמים ושרי המדינות לפניו׃

דברי נחמיה בן חכליה; ויהי בחדש כסלו שנת עשרים ואני הייתי בשושן הבירה׃

ואצוה את חנני אחי ואת חנניה שר הבירה על ירושלם; כי הוא כאיש אמת וירא את האלקים מרבים׃

The obvious suggestion is that בירה is a Persian loan word. The Farsi word for tower is برج, burj (I think that’s the transliteration), as in the Burj Khalifa. But Rabbi Leibtag suggests the reverse: בירה primarily refers to Jerusalem, and שושן הבירה is an ironic reference to the assimilation of Persian Jews.

Hence we can conclude that the Megilla’s satire suggests that during this time period Am Yisrael had replaced:

- G-d with Achashverosh;

- G-d’s Temple with Achashverosh’s palace; and

- Yerushalayim ha-bira with Shushan ha-bira!

David intends to build the בירה in Jerusalem, but by the time of Esther, the Jews feel their בירה is in Persia. It’s similar to the sentiment expressed by the Meshech Chochma:

עוד מעט ישוב לאמר ”שקר נחלו אבותינו“, והישראלי בכלל ישכח מחצבתו ויחשב לאזרח רענן. יעזוב לימודי דתו, ללמוד לשונות לא לו…יחשוב כי ברלין היא ירושלים…אז יבוא רוח סועה וסער, יעקור אותו מגזעו יניחהו לגוי מרחוק אשר לא למד לשונו, ידע כי הוא גר.

That’s the danger of this בירה: it will be simply an impressive tower, that can be replaced with other impressive towers. But that’s not where the Jews are now. They are going to build the בירה to be the בית אלקים. David describes how much money and raw materials he’s accumulated.

וככל כחי הכינותי לבית אלקי הזהב לזהב והכסף לכסף והנחשת לנחשת הברזל לברזל והעצים לעצים; אבני שהם ומלואים אבני פוך ורקמה וכל אבן יקרה ואבני שיש לרב׃

He emphasizes that he has the הזהב לזהב והכסף לכסף, because the plans may call for gold and silver but they might not have been able to afford that. Later in history, they will have to substitute:

כה ויהי בשנה החמישית למלך רחבעם; עלה שושק (שישק) מלך מצרים על ירושלם׃ כו ויקח את אצרות בית ה׳ ואת אוצרות בית המלך ואת הכל לקח; ויקח את כל מגני הזהב אשר עשה שלמה׃ כז ויעש המלך רחבעם תחתם מגני נחשת; והפקיד על יד שרי הרצים השמרים פתח בית המלך׃

Even the כלי המקדש can be made of cheaper materials if they can’t afford the gold:

כדתניא: לא יעשה אדם בית תבנית היכל…רבי יוסי בר יהודה אומר: אף של עץ לא יעשה, כדרך שעשו מלכי בית חשמונאי…שפודין של ברזל היו וחיפום בבעץ. העשירו—עשאום של כסף, חזרו העשירו—עשאום של זהב.

And in Yeshaya’s vision of the future בית המקדש we will be able to afford to build things the way they were intended.

תחת הנחשת אביא זהב ותחת הברזל אביא כסף ותחת העצים נחשת ותחת האבנים ברזל; ושמתי פקדתך שלום ונגשיך צדקה׃

And then David describes the construction budget:

ג ועוד ברצותי בבית אלקי יש לי סגלה זהב וכסף; נתתי לבית אלקי למעלה מכל הכינותי לבית הקדש׃ ד שלשת אלפים ככרי זהב מזהב אופיר; ושבעת אלפים ככר כסף מזקק לטוח קירות הבתים׃

ברצותי: בעבור שאני מרוצה וחפץ בבית ה׳ הנה יש לי עוד סגולה מיוחדת מזהב וכסף נתתי גם אותה לבית ה׳

But despite all that, when Shlomo actually builds the בית המקדש, he apparently doesn’t use all that gold and silver:

ותשלם כל המלאכה אשר עשה שלמה לבית ה׳;

ויבא שלמה את קדשי דויד אביו ואת הכסף ואת הזהב ואת כל הכלים נתן באצרות בית האלקים׃

We’ve talked about the reason why in Once Upon a Midnight Dreary.

ויבא שלמה את קדשי דוד אביו: ולמה לא נצרך להם…מי שדורש לגנאי על שבא הרעב בימי דוד שלש שנים וכמה תסבריות היו לו לדוד, צבורין מכסף וזהב מה שהיה מתקין לבית המקדש היה צריך להוציאו ולהחיות בו את הנפשות ולא עשה כן, אמר לו הקדוש ברוך הוא בני מתים ברעב ואתה צובר ממון לבנות בו בנין! חייך אין שלמה נצרך מהם כלום.

David seems to have a blind spot. He has just said (דברי הימים א פרק כח:ג), והאלקים אמר לי לא תבנה בית לשמי כי איש מלחמות אתה ודמים שפכת, but he doesn’t seem to understand what that implies.

And then, after describing how much money he’s budgeted, he asks for donations.

ה לזהב לזהב ולכסף לכסף ולכל מלאכה ביד חרשים; ומי מתנדב למלאות ידו היום לה׳׃ ו ויתנדבו שרי האבות ושרי שבטי ישראל ושרי האלפים והמאות ולשרי מלאכת המלך׃ ז ויתנו לעבודת בית האלקים זהב ככרים חמשת אלפים ואדרכנים רבו וכסף ככרים עשרת אלפים ונחשת רבו ושמונת אלפים ככרים; וברזל מאה אלף ככרים׃ ח והנמצא אתו אבנים נתנו לאוצר בית ה׳ על יד יחיאל הגרשני׃ ט וישמחו העם על התנדבם כי בלב שלם התנדבו לה׳; וגם דויד המלך שמח שמחה גדולה׃

Why solicit donations? He’s already said that he has enough. I think the reason is the same as the reason that the original משכן had to be made from donations.

דבר אל בני ישראל ויקחו לי תרומה; מאת כל איש אשר ידבנו לבו תקחו את תרומתי׃

והמלאכה היתה דים לכל המלאכה לעשות אתה; והותר׃

ואולי שישמיענו הכתוב חיבת בני ישראל בעיני המקום, כי לצד שהביאו ישראל יותר משיעור הצריך, חש ה׳ לכבוד כל איש שטרחו והביאו ונכנס כל המובא בית ה׳ במלאכת המשכן, וזה שיעור הכתוב והמלאכה אשר צוה ה׳ לעשות במשכן הספיקה להכנס בתוכה כל המלאכה שעשו בני ישראל הגם שהותר; פירוש שהיה יותר מהצריך הספיק המקבל לקבל יותר משיעורו על ידי נס. או על זה הדרך והמלאכה שהביאו היתה דים לא חסר ולא יותר הגם שהיתה יותר כפי האמת והוא אומרו והותר כי נעשה נס ולא הותיר.

It was important that every single member of the community felt that they had a part in building the משכן. Without that sense of community, the physical building would be pointless.

ועשו לי מקדש; ושכנתי בתוכם׃

Having set up the building fund, David concludes with a ברכה of thanksgiving to הקב״ה.

ויברך דויד את ה׳ לעיני כל הקהל; ויאמר דויד ברוך אתה ה׳ אלקי ישראל אבינו מעולם ועד עולם׃

He specifically addresses אלקי ישראל אבינו:

ויברך דויד את ה׳ לעיני כל הקהל וגו׳: אלקי אברהם יצחק וישראל אינו אומר כאן, אלא ”אלקי ישראל אבינו“, תלה את הנדר במי שפתח בו תחלה.

David sees himself as finally fulfilling the vow that Yaakov had made seven centuries before.

כ וידר יעקב נדר לאמר; אם יהיה אלקים עמדי ושמרני בדרך הזה אשר אנכי הולך ונתן לי לחם לאכל ובגד ללבש׃…כב והאבן הזאת אשר שמתי מצבה יהיה בית אלקים; וכל אשר תתן לי עשר אעשרנו לך׃

א שיר המעלות; זכור ה׳ לדוד את כל ענותו׃ ב אשר נשבע לה׳; נדר לאביר יעקב׃ ג אם אבא באהל ביתי; אם אעלה על ערש יצועי׃ ד אם אתן שנת לעיני; לעפעפי תנומה׃ ה עד אמצא מקום לה׳; משכנות לאביר יעקב׃

And the text of this ברכה is familiar:

יא לך ה׳ הגדלה והגבורה והתפארת והנצח וההוד כי כל בשמים ובארץ; לך ה׳ הממלכה והמתנשא לכל לראש׃ יב והעשר והכבוד מלפניך ואתה מושל בכל ובידך כח וגבורה; ובידך לגדל ולחזק לכל׃ יג ועתה אלקינו מודים אנחנו לך; ומהללים לשם תפארתך׃ יד וכי מי אני ומי עמי כי נעצר כח להתנדב כזאת; כי ממך הכל ומידך נתנו לך׃ טו כי גרים אנחנו לפניך ותושבים ככל אבתינו; כצל ימינו על הארץ ואין מקוה׃ טז ה׳ אלקינו כל ההמון הזה אשר הכיננו לבנות לך בית לשם קדשך; מידך היא (הוא) ולך הכל׃ יז וידעתי אלקי כי אתה בחן לבב ומישרים תרצה; אני בישר לבבי התנדבתי כל אלה ועתה עמך הנמצאו פה ראיתי בשמחה להתנדב לך׃ יח ה׳ אלקי אברהם יצחק וישראל אבתינו שמרה זאת לעולם ליצר מחשבות לבב עמך; והכן לבבם אליך׃ יט ולשלמה בני תן לבב שלם לשמור מצותיך עדותיך וחקיך; ולעשות הכל ולבנות הבירה אשר הכינותי׃

I want to focus on those first psukim, the list of praises of ה׳, from הגדלה והגבורה to ממלכה והמתנשא.

במתניתא תנא משמיה דרבי עקיבא; ”לך ה׳ הגדולה“ זו קריעת ים סוף, ”והגבורה“ זו מכת בכורות, ”והתפארת“ זו מתן תורה, ”והנצח“ זו ירושלים, ”וההוד“ זו בית המקדש.

The implication is that each of these represents a different aspect of ה׳'s manifestation in the world.

וכאילו בא לומר כי מצד גדולתו…היה קריעת ים סוף, שהיא בריאה גמורה [הערת הרב יהושע הרטמן: בקריעת ים סוף נבראה הבריאה העיקרית שבעולם, והיא כנסת ישראל]. ומצד גבורתו יתברך היה מכת בכורות…ומצד תפארתו נתן תורה לישראל, ומצד הנצחות של השם יתברך נתן לירושלים הנצחות [הערת הרב יהושע הרטמן: ירושלים היא עיקר ארץ ישראל…ומצינו לגבי ארץ ישראל שהתורה מדגישה שהיא נחלה נצחית], ומצד ההוד של השם יתברך היה בית המקדש, שבו הודו של השם יתברך.

ומצד ההוד של השם יתברך היה בית המקדש: נקודה זו צריכה ביאור, דבשלמא כל המדות שנזכרו עד כה, הם באו לידי בטוי במעשים שהקב״ה בכבודו ובעצמו עשה [קריעת ים סוף, מכת בכורות, מתן תורה, ונצחיות ירושלים]…אך ההוד של בית המקדש הוא לכאורה מחמת ישראל, וכפי שכתב הגר״א (אמרי נועם, ברכות נח,א) ”וההוד זה בית המקדש, שבמקדש אומרים שירות ותשבחות“, והרי ישראל הם אלו האומרים שירות ותשבחות…

ושם [גבורות השם] ר״פ עא כתב ”כי בית המקדש העיקר שלו אינו העצים והאבנים, שהם טפלים אצל עיקר המקדש, שהוא המדריגה הנבדלת שיש במקדש, כמו שטפל הגוף של אדם אצל הנשמה“…הרי מעלת בית המקדש היא השכינה השורה בבנין שנבנה על ידי בני אדם.

As we said last time, the בית המקדש is the לבנת הספיר, the prism, through which ה׳'s manifestation in the world is refracted into the actions of human beings, the מעשה צדיקים. Later kabbalists took the terms that David used, הגדלה והגבורה והתפארת והנצח וההוד etc., and called them the “ספירות”.

The sefirot are 10 emanations, or illuminations of G-d’s infinite light as it manifests in creation. As revelations of the creator’s will (רצון), the sefirot [are] 10 different channels through which the one G-d reveals His will.

הכתוב סדרן כמדתן, שהם ז׳ ספירות האחרונות כסדרן, כמ״ש בזה חכמי הקבלה.

| דברי הימים | ספירות |

|---|---|

| גדלה | חסד |

| גבורה | דין |

| תפארת | תפארת |

| נצח | נצח |

| הוד | הוד |

| כל בשמים ובארץ | יסוד |

| ממלכה ומתנשא | מלכות |

I don’t know that David had this intricate theological system in mind, but he clearly means that everything in the world, including our very existence, is a manifestation of ה׳'s goodness in the world. And מודים אנחנו לך, part of our task is to acknowlege that. If the Jews start focusing on the glory of the building instead of its meaning, it will end in disaster.

אל תבטחו לכם אל דברי השקר לאמר; היכל ה׳ היכל ה׳ היכל ה׳ המה׃

I would like to look at two perakim of תהילים that highlight how we are to bring the “light” of הקב״ה into the world.

א למנצח שיר מזמור; הריעו לאלקים כל הארץ׃

ב זמרו כבוד שמו; שימו כבוד תהלתו׃

ג אמרו לאלקים מה נורא מעשיך; ברב עזך יכחשו לך איביך׃

ד כל הארץ ישתחוו לך ויזמרו לך; יזמרו שמך סלה׃

JPS translates הריעו לאלקים כל הארץ as “Raise a shout for G-d, all the earth”, but Hirsch translates הריעו as “waken”. This psalm is looking toward a day when everyone will be awakened to praise ה׳ and (in the next verse) His כבוד, which is always used for the manifestation of הקב״ה in the created world, and therefore, אמרו לאלקים מה נורא מעשיך.

נורא is in the singular, where מעשיך is plural. The נורא, awesomeness, describes the sum total of מעשיך. Rav Soloveitchik calls that sense of נורא, ”numinous“, a term coined by Rudolf Otto to mean a (from Wikipedia) “non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self”. It (from Britannica Online) “evades precise formulation in words. Like the beauty of a musical composition, it is non-rational and eludes complete conceptual analysis; hence it must be discussed in symbolic terms”.

The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its “profane,” non-religious mood of everyday experience…It may become the hushed, trembling, and speechless humility of the creature in the presence of—whom or what? In the presence of that which is a Mystery inexpressible and above all creatures.

We express this idea in שחרית for שבת. There are four descriptions of ה׳ that we use in davening:

כי ה׳ אלקיכם הוא אלקי האלהים ואדנ־י האדנים; הא־ל הגדל הגבר והנורא אשר לא ישא פנים ולא יקח שחד׃

ועתה אלקינו הא־ל הגדול הגבור והנורא שומר הברית והחסד אל ימעט לפניך את כל התלאה אשר מצאתנו למלכינו לשרינו ולכהנינו ולנביאינו ולאבתינו ולכל עמך; מימי מלכי אשור עד היום הזה׃

And we define all of those in נשמת:

מי ידמה לך ומי ישוה לך ומי יערך לך, הא־ל הגדול הגבור והנורא…

הא־ל, בתעצמות עזך. הגדול, בכבוד שמך. הגבור, לנצח. והנורא בנוראותיך

The one that is left undefined is נורא. נורא is ineffable.

But what are we supposed to do with that feeling?

יב ועתה ישראל מה ה׳ אלקיך שאל מעמך; כי אם ליראה את ה׳ אלקיך ללכת בכל דרכיו ולאהבה אתו ולעבד את ה׳ אלקיך בכל לבבך ובכל נפשך׃ יג לשמר את מצות ה׳ ואת חקתיו אשר אנכי מצוך היום לטוב לך׃

G-d “only” wants one thing: ליראה and ללכת and לאהבה and לעבד and לשמר! The way to read this (as we discussed in פרשת עקב תשפ״א) is that really, ה׳ wants only one thing: ליראה את ה׳ אלקיך, to feel the נורא, so that the rest follows: ללכת בכל דרכיו ולאהבה אתו, etc.

ואמר רבי חנינא: הכל בידי שמים, חוץ מיראת שמים. שנאמר: וְעַתָּה יִשְׂרָאֵל מָה ה׳ אֱלֹקֶיךָ שׁוֹאֵל מֵעִמָּךְ כִּי אִם לְיִרְאָה.

הנועם אלימלך מבאר ששואל מעמך, אין הכוונה דורש מעמך, אלא מלשון ”שאלת כלים“ וכדי לבאר את הפסוק מביא ר׳ אלימלך מליז׳נסק משל לאדם שרוצה לשלוח לחברו שמן ודבש ואין לו כלים נאים מתאימים, שואל מחברו את הכלים המיוחדים ומשגר בהם את השמן והדבש. הנמשל—האדם הוא הכלי לקבל את השפע האלוקי, הקב״ה שואל מאתנו את הכלי כלומר את עצמנו, אולם נותן לנו הדרכה כיצד הכלי יהיה מותאם לשפע האינסופי כשנעבוד על כל הדברים המנויים בפסוק ואז ישאל מאתנו את הכלי לְטוֹב לָךְ—כדי להטיב עימנו.

ה׳ asks to “borrow” our יראת שמים, our awe of the Divine, that we freely choose to acknowledge, so that He can “fill” it will all the מצוות that will allow us to fulfill the ultimate purpose of creation.

[T]he Torah’s main objective is the translation of the numinous into the kerygmatic…

We need to spread that feeling of נורא to the rest of the world, not so much by preaching as by being an example.

ה לכו וראו מפעלות אלקים; נורא עלילה על בני אדם׃

ו הפך ים ליבשה בנהר יעברו ברגל; שם נשמחה בו׃

ז משל בגבורתו עולם עיניו בגוים תצפינה;

הסוררים אל ירימו (ירומו) למו סלה׃

That sense of נורא, of the numinous, is in the experience of miracle; עלילה means deeds that have a cause, a reason (Google translates לעליל ועלול as “for all intents and purposes”).

עלילות הם הפעולות ששרשם מכח תכונות מוסריות, ואצל ה׳ הנפלאות שיעשה ששרשם מפאת תכונת הצדק והמישרים ויתר מדותיו.

The open miracles of קריעת ים סוף and קרעית הירדן, and we sang שירה there (שם נשמחה בו), but Radak points out that נשמחה is in the future tense. It is a hint to the ultimate גאולה which will also be an awesome miracle:

שם. גם כן נשמחה בו בהוציאו אותנו מגלות.

טו והחרים ה׳ את לשון ים מצרים והניף ידו על הנהר בעים רוחו; והכהו לשבעה נחלים והדריך בנעלים׃ טז והיתה מסלה לשאר עמו אשר ישאר מאשור; כאשר היתה לישראל ביום עלתו מארץ מצרים׃

In the bigger picture, the most inspiring miracle is the survival of the Jewish people:

ח ברכו עמים אלקינו; והשמיעו קול תהלתו׃

ט השם נפשנו בחיים; ולא נתן למוט רגלנו׃

י כי בחנתנו אלקים; צרפתנו כצרף כסף׃

יא הבאתנו במצודה; שמת מועקה במתנינו׃

יב הרכבת אנוש לראשנו; באנו באש ובמים; ותוציאנו לרויה׃

We all known Mark Twain’s essay, Concerning the Jews:

If the statistics are right, the Jews constitute but one per cent. of the human race. It suggests a nebulous dim puff of star-dust lost in the blaze of the Milky Way. Properly the Jew ought hardly to be heard of; but he is heard of, has always been heard of. He is as prominent on the planet as any other people, and his commercial importance is extravagantly out of proportion to the smallness of his bulk. His contributions to the world’s list of great names in literature, science, art, music, finance, medicine, and abstruse learning are also away out of proportion to the weakness of his numbers.

He has made a marvellous fight in this world, in all the ages; and has done it with his hands tied behind him. He could be vain of himself, and be excused for it. The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, then faded to dream-stuff and passed away; the Greek and the Roman followed, and made a vast noise, and they are gone; other peoples have sprung up and held their torch high for a time, but it burned out, and they sit in twilight now, or have vanished.

The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts, no slowing of his energies, no dulling of his alert and aggressive mind. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?

He doesn’t answer the question, but earlier in the essay he has a wry Twain-ian comment:

Last week in Vienna a hailstorm struck the prodigious Central Cemetery and made wasteful destruction there. In the Christian part of it, according to the official figures, 621 window-panes were broken; more than 900 singing-birds were killed; five great trees and many small ones were torn to shreds and the shreds scattered far and wide by the wind; the ornamental plants and other decorations of the graves were ruined, and more than a hundred tomb-lanterns shattered; and it took the cemetery’s whole force of 300 laborers more than three days to clear away the storm’s wreckage. In the report occurs this remark—and in its italics you can hear it grit its Christian teeth “…lediglich die israelitische Abtheilung des Friedhofes vom Hagelwetter ganzlich verschont worden war” [Google translate: only the Israelite section of the cemetery had been completely spared from the hailstorm]. Not a hailstone hit the Jewish reservation! Such nepotism makes me tired.

The secret of Jewish immortality is Divine nepotism.

ואמרת אל פרעה; כה אמר ה׳ בני בכרי ישראל׃

But that is all the direct manifestation of ה׳ in the world. The psalmist wants to make it relevant, kerygmatic.

יג אבוא ביתך בעולות; אשלם לך נדרי׃

יד אשר פצו שפתי; ודבר פי בצר לי׃

טו עלות מיחים אעלה לך עם קטרת אילים;

אעשה בקר עם עתודים סלה׃

Sacrifices are one thing, but they are not the point. The psalmist addresses כל יראי אלקים , the ones who feel the נורא and need to translate that into action.

טז לכו שמעו ואספרה כל יראי אלקים; אשר עשה לנפשי׃

יז אליו פי קראתי; ורומם תחת לשוני׃

יח און אם ראיתי בלבי לא ישמע אדנ־י׃

יט אכן שמע אלקים; הקשיב בקול תפלתי׃

כ ברוך אלקים אשר לא הסיר תפלתי וחסדו מאתי׃

I thank ה׳ that I still have my תפלה. That is how to use יראה, to tell the world, זמרו כבוד שמו:

ברוך: שעזרני להתפלל ולא הסיר וחסדו היה שאתפלל אליו.

The next perek is similar, exhorting the entire world to praise ה׳. It has an interesting background.

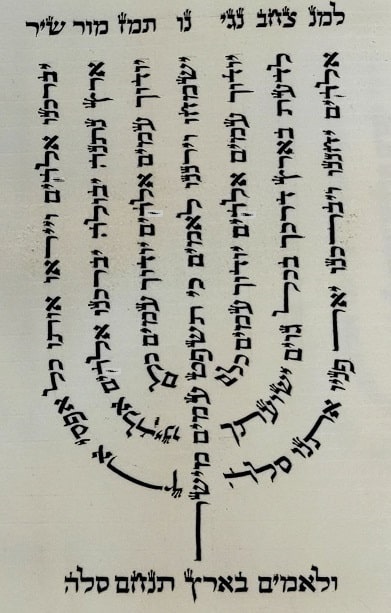

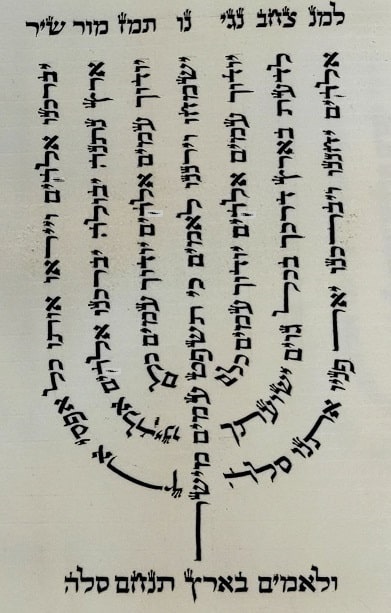

דוד הע״ה הראהו הקב״ה ברוח הקדש מזמור ”למנצח בנגינות מזמור שיר אלקים יחננו וכו׳“ כתוב על טס של זהב מופז עשוי בצורת מנורה…והיה דוד הע״ה נושא זה המזמור כתוב ומצוייר וחקוק במגינו בטס של זהב כצורת מנורה. כשהיה יוצא למלחמה והיה מכוין סודו והיה נוצח אותם ואויביו נופלים לפניו…העתיקו מכתיבת יד הקדש של הגאון מהרש״ל ז״ל ושם כתוב סודות ונפלאות הרמוזות במזמור הנזכר.

Setting aside the kabbalistic סודות ונפלאות and the midrashic meaning of the מגן דוד, writing this perek בצורת מנורה makes the chiastic structure of the perek clear. Turning it on its side (note that the psukim are now bottom to top) shows the structure:

א למנצח בנגינת מזמור שיר׃

ב אלקים יחננו ויברכנו; יאר פניו אתנו סלה׃

ג לדעת בארץ דרכך; בכל גוים ישועתך׃

ד יודוך עמים אלקים; יודוך עמים כלם׃

ה ישמחו וירננו לאמים;

כי תשפט עמים מישר; ולאמים בארץ תנחם סלה׃

ו יודוך עמים אלקים; יודוך עמים כלם׃

ז ארץ נתנה יבולה; יברכנו אלקים אלקינו׃

ח יברכנו אלקים; וייראו אותו כל אפסי ארץ׃

It starts with אלקים יחננו ויברכנו and ends with יברכנו אלקים, then pairs לדעת בארץ דרכך with ארץ נתנה יבולה, then uses the same pasuk twice, יודוך עמים אלקים and centers the chiasmus on ישמחו וירננו לאמים כי תשפט עמים מישר.

The other structural aspect of this perek is that it contains 49 words, corresponding to the days of the Omer (7x7), and we have the minhag to recite it as part of counting the Omer.

I asked ChatGPT why we recite Psalm 67 when we count the Omer.

Psalm 67 (Chapter 67) is not recited during the counting of the Omer. The most common chapter recited during the Omer period is Psalm 49 (Chapter 49). Psalm 49 is chosen because it includes a verse that refers to “arbitrary Arab wealth,” thereby fulfilling the Omer tradition. This chapter is included in the sequence of the eighteen blessings (Amidah) between Maimonides' and the Sephardic versions, and it is recited for the first time on the evening of the fifth day of the Omer, preceding the prayer on the sixth day. In Jewish tradition, the counting of the Omer is the order of counting the Omer offering, which is observed by the priests from the offering of the Omer on the second day of Passover until the holiday of Shavuot, beginning on the evening after the holy Sabbath following Passover.

That is so far from the truth that it isn’t even wrong. There isn’t a correct statement in there. The only conclusion I can come to is that this perek is so deep and mystical that it causes hallucinations in artificial intelligences. So that isn’t very useful.

Let’s look at this perek.

א למנצח בנגינת מזמור שיר׃

ב אלקים יחננו ויברכנו; יאר פניו אתנו סלה׃

The expression of יחננו ויברכנו; יאר פניו אתנו is clearly an allusion to ברכת כהנים:

כב וידבר ה׳ אל משה לאמר׃ כג דבר אל אהרן ואל בניו לאמר כה תברכו את בני ישראל; אמור להם׃

כד יברכך ה׳ וישמרך׃

כה יאר ה׳ פניו אליך ויחנך׃

כו ישא ה׳ פניו אליך וישם לך שלום׃

כז ושמו את שמי על בני ישראל; ואני אברכם׃

But it’s missing the last verse: ישא ה׳ פניו אליך. We looked at these ברכות in פרשת נשא תשפ״ב. Rashi explains יאר פניו:

יאר השם פניו אליך: יַרְאֶה לְךָ פָּנִים שׂוֹחֲקוֹת, פָּנִים צְהֻבּוֹת.

We know what a smiling yellow face is:

😊

But Rashi explains the next verse very differently:

ישא ה׳ פניו אליך: יִכְבֹּשׁ כַּעֲסוֹ.

יָאֵר ה׳ וגו׳: שֶׁיַּבִּיט בְּךָ בְּפָנִים מְאִירוֹת וְלֹא בְּפָנִים זְעוּמוֹת.

ישא ה׳ פניו אליך וגו׳: יעביר כעסו ממך, ואין ”ישא“ אלא לשון הסרה…”פניו“, אלו פנים של זעם…כלומר אותם פנים של זעם שהיו ראויות לבוא אליך יסירם ממך.

😠

The third verse is not synonymous with the second. The second, יאר פניו, is that ה׳ should be happy with you. The third, ישא פניו, is that when ה׳ is angry, He should not show you His face. ישא ה׳ פניו אליך should be parsed as “May ה׳ take away His פניו אליך, the angry face that He is going to show you”.

This is a highly startling “blessing”! Would not “May the Lord not be angry with you!” be more of a blessing?

We explained that ברכת כהנים acknowledges that we are not perfect, that we don’t always deserve ברכה. But even then, we can ask for ה׳'s רחמים, that he “turn aside” and overlook our imperfections.

But our perek here leaves that thought out. It is all positive, all about the divine “light” that we keep coming back to. That is the image of the menorah, that spreads its light out to the world.

ויעש לבית חלוני שקפים אטומים׃

ויעש לבית חלוני שקופים אטומים: תנא שקופין מבפנים ואטומים מבחוץ: לא לאורה אני צריך.

תדע כשאדם בונה בית עושה לו חלונות צרות מבחוץ ורחבות מבפנים, כדי שיהא האור נכנס מבחוץ ומאיר מבפנים, ושלמה שבנה בית המקדש לא עשה כך אלא עשה חלונות צרות מבפנים ורחבות מבחוץ, כדי שיהא האור יוצא מבית המקדש ומאיר לחוץ, שנאמר: ”ויעש לבית חלוני שקפים אטומים“, להודיעך שכלו אור ואין צריך לאורם.

And that is the connection with the Omer. As we said above and in Blueprints, the ספירות represent the way we classify that divine “light”, refracted through our sensations of the universe around us, and through our own actions. The period of the Omer is when we are supposed to work on those מידות, so we become the prism about which we can say, יאר פניו אתנו. The first pasuk of ברכת כהנים and the first half of our pasuk here, אלקים יחננו ויברכנו, is for our own ברכה, that we are prosperous. The second is that we should spread that light to others.

וראה את הכסא כמראה אבן ספיר שהוא מוכן לקבל כל המראות…וחזה השפע היורדת מהאלקות…בשבעה גווני הקשת…ונקרא אבן ספיר על שם…שמושך הכח מהספירות שלמעלה.

And through us, the light spreads through the world.

ג לדעת בארץ דרכך; בכל גוים ישועתך׃

ד יודוך עמים אלקים; יודוך עמים כלם׃

That is our mission, לתקן עולם במלכות שד־י. And that leads to the apex of the chiasmus:

ישמחו וירננו לאמים; כי תשפט עמים מישר; ולאמים בארץ תנחם סלה׃

We look to a day when the world will rejoice over the fact that ה׳ judges and leads them, וכל בני בשר יקראו בשמך.

The last stich is the consequence of יודוך עמים כלם: the מלכות שד־י leads to material prosperity.

ו יודוך עמים אלקים; יודוך עמים כלם׃

ז ארץ נתנה יבולה; יברכנו אלקים אלקינו׃

And the last pasuk is parallel to the first, אלקים יחננו ויברכנו. But now the psalmist makes the point that the goal for our prosperity, our ברכה, is to spread יראת ה׳ throughout the world.

יברכנו אלקים; וייראו אותו כל אפסי ארץ׃

ארץ נתנה יבולה is not a reward in the sense of a payment for what we have done; it is a gift to allow us to move forward.

נמצא פירוש כל אותן הברכות והקללות על דרך זו; כלומר אם עבדתם את ה׳ בשמחה ושמרתם דרכו משפיע לכם הברכות האלו ומרחיק הקללות עד שתהיו פנויים להתחכם בתורה ולעסוק בה כדי שתזכו לחיי העולם הבא וייטב לך לעולם שכולו טוב ותאריך ימים לעולם שכולו ארוך…

Nothing we have in this world is because we deserve it; ה׳ gives us the benefits of this world in order to allow us to fulfill the תורה. If you have done מיצוות, Hashem will give you the tools—health, wealth, influence—that will allow you to do more מיצוות. It’s like getting a second round of venture capital funding. At each stage, the funder looks at what you’ve managed to do with what you had before deciding that you should get more money. The big payoff at the IPO doesn’t happen until much later. So too, we need to realize that the gifts we have, that Hashem grants us, are tools, not rewards. We have to use them to give to others and then we will be granted more of those gifts.

And so this perek is symbolized by the menorah, spreading light throughout the world.

המזמור נכתב בצורת המנורה שהיא סמל הלאום שלנו, ובה מדליקים את הנרות כלפי חוץ—ללמדנו שאין למנורה שלנו תפקיד קטן ופרטיקולרי, אלא אוניברסלי—להיות אור לגויים. כמו כן, את המזמור הזה אנו אומרים בספירת העומר, בימים שבין חג הפסח לחג השבועות, בין גאולתנו הלאומית לבין מתן תורה שבה יש את המסר האוניברסלי והתפקיד האוניברסלי של עם ישראל.

But how does that connect to the מגן דוד, that the חידא said כשהיה יוצא למלחמה והיה מכוין סודו והיה נוצח? Note that this is not the hexagram (✡) that we generally associate with the term מגן דוד, but the menorah with תהילים פרק סז. I think the message of the midrash is that the “real” David, the one we are meant to remember and tell the story of, is not the warrior of ספר שמואל but the psalmist of ספר תהילים. When he was יוצא למלחמה, היה מכוין סודו, and realize that true victory was not a military conquest, but ישמחו וירננו לאמים.