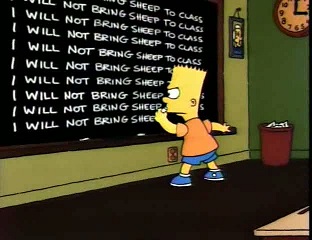

- peccavi

- An acknowledgment of sin, literally in Latin, “I have sinned”

General Sir Charles Napier, commanding the East India Company’s Bombay Presidency army, defeated the Muslim rulers of Sindh. He then proceeded, against orders, to conquer the entire province.

He informed his superiors by sending a single-word despatch: ‘Peccavi’— the Latin for “I have sinned.”

יג ויאמר דוד אל נתן חטאתי לה׳;

ויאמר נתן אל דוד גם ה׳ העביר חטאתך לא תמות׃

יד אפס כי נאץ נאצת את איבי ה׳ בדבר הזה; גם הבן הילוד לך מות ימות׃

Even though it wasn’t explicitly mentioned in Nathan’s speech to David, (he spoke of לא תסור חרב מביתך and לקחתי את נשיך לעיניך ונתתי לרעיך) it’s clear that if not for David’s חטאתי he would have died. David is facing the same fate as Saul: to die ignominiously, to lose four of his children, and to lose the kingship. The difference is in their reactions to the news. Saul goes into denial:

כ ויאמר שאול אל שמואל אשר שמעתי בקול ה׳ ואלך בדרך אשר שלחני ה׳; ואביא את אגג מלך עמלק ואת עמלק החרמתי׃

כא ויקח העם מהשלל צאן ובקר ראשית החרם לזבח לה׳ אלקיך בגלגל׃

David simply says חטאתי לה׳. He admits his guilt. And ה׳ commutes his death sentence, but the other parts of his punishment remain. That’s because תשובה is more than just confession:

א כל המצוות שבתורה…אם עבר אדם על אחת מהן…כשיעשה תשובה וישוב מחטאו, חייב להתוודות…

ב כיצד מתוודה? אומר אנא ה׳ חטאתי עוויתי פשעתי לפניך, ועשיתי כך וכך, והרי ניחמתי ובושתי במעשיי, ולעולם איני חוזר לדבר זה…

מדברי רמב״ם אלו עולה, כי סדר התשובה הוא כך: א. הווידוי הוא הראשון. ב. החרטה על העבר.

ג. ”קבלה לעתיד“ שלא יחטא.

The remainder of ספר שמואל is fundamentally the story of David’s תשובה. The punishment still happens; he loses four sons as we discussed last time, and he will lose his kingdom and see his wives publicly taken from him, but he will regain that kingship and end up with a son, Shlomo, who continues his legacy.

There is a well-known פרק תהילים that expands David’s mental state with his חטאתי לה׳, that we quote three times a day. It is the true expression of David’s ווידוי:

א למנצח מזמור לדוד׃

ב בבוא אליו נתן הנביא כאשר בא אל בת שבע׃

ג חנני אלקים כחסדך; כרב רחמיך מחה פשעי׃

ד הרבה (הרב) כבסני מעוני; ומחטאתי טהרני׃

ה כי פשעי אני אדע; וחטאתי נגדי תמיד׃

David asks for forgiveness for his sin, and admits that he sinned—פשעי אני אדע— but doesn’t mention the sin. The Rambam points out that a true ווידוי needs to be specific: ועשיתי כך וכך. Rabbi Avi Baumol points out that the כותרת is part of the פרק, and it is very specific: כאשר בא אל בת שבע.

This verse, which is the title of psalm, is quite incriminating. If we accept the assumption that the songs of David were not his private hymns, but rather a popular vehicle for connecting with G-d during his time and eternally, then we have a strange phenomenon. David publicly incriminates himself!

Could David not have left out this damning verse? Would he not have saved face by not revealing to the nation his desires, his iniquities and his darkest actions? Why include this psalm at all in the songs of David?

…Despite the fact that the prophet told David his repentance was genuinely accepted and that he would not lose his kingdom or his life, David did not feel exonerated, since his repentance happened in private, behind royally closed doors. As representative of the nation, he felt he must make a statement pouring out his shame before his ministers, his army and the peasants who work the fields. He would write a song, a story of his sin, his darkest hour and his forgiving G-d who saw his genuine teshuva and granted him another chance.

…In this regard, Psalm 51 belongs in the Psalter, perhaps even with distinction, as it represents a defining quality of leadership which appeared in David but rarely in anyone before or after him.

לך לבדך חטאתי והרע בעיניך עשיתי;

למען תצדק בדברך תזכה בשפטך׃

לך לבדך חטאתי is the hardest pasuk to understand. His sin was against Bat Sheva and Uriah; what does לך לבדך mean? Certainly Nathan accuses him of sinning against G-d as well: (שמואל ב יב:ט) מדוע בזית את דבר ה׳ לעשות הרע בעינו. When David abuses his power for his own personal needs, it is a חלול ה׳:

ונראה שדבר ה׳ אשר בזה הוא אשר דבר להמליכו, שעכשיו בִּזָה אותו דבר שיאמר ראו אשר בחר בו ה׳…

And David will certainly have to do תשובה for what happened to Bat Sheva and Uriah; we’ve talked about the concept of יבום, and the requirement for an אונס to marry his victim. But Rabbi Baumol points out that’s not what this perek is about.

לך לבדך: כי דבר בת שבע בסתר היה ואין יודע זולתך…ואתה ידעת בשני הדברים כי לבבי להרע ולא אכפור בחטא. והגאון רב סעדיה פירוש…”לך“ כלומר אני מתודה ואומר ”חטאתי“, לך לבדך, ולא אפרסם החטא לזולתי.

In other words, פשעי אני אדע, I publicly acknowledge my sin, even though לך לבדך חטאתי, only You knew the truth about it, למען תצדק בדברך, in order to demonstrate Your justice. As Rabbi Baumol says (p. 111) “I thought my sin would be only before G-d but now I realize that I must confess my sin before all my peers”.

ודוד המלך עליו השלום בהתודותו על חטאו בבוא אליו נתן הנביא אמר בסוף דבריו (תהלים נא) זבחי אלקים רוח נשברה לב נשבר ונדכה אלקים לא תבזה. רוח נשברה. רוח נמוכה. למדנו מזה כי ההכנעה מעיקרי התשובה. כי המזמור הזה יסוד מוסד לעיקרי התשובה.

ז הן בעוון חוללתי; ובחטא יחמתני אמי׃

ח הן אמת חפצת בטחות; ובסתם חכמה תודיעני׃

ט תחטאני באזוב ואטהר; תכבסני ומשלג אלבין׃

י תשמיעני ששון ושמחה; תגלנה עצמות דכית׃

יא הסתר פניך מחטאי; וכל עונתי מחה׃

יב לב טהור ברא לי אלקים; ורוח נכון חדש בקרבי׃

יג אל תשליכני מלפניך; ורוח קדשך אל תקח ממני׃

יד השיבה לי ששון ישעך; ורוח נדיבה תסמכני׃

טו אלמדה פשעים דרכיך; וחטאים אליך ישובו׃

The next part of the perek sets up the fundamental dialectic of humanity: בעוון חוללתי but לב טהור ברא לי אלקים. First he deals with the negative: I was conceived in sin. But this isn’t the Christian concept of Original Sin, that we start life having already sinned. We are only born with a tendency to self-interest (יצר הרע): (בראשית ד:ז) לפתח חטאת רבץ. Deep inside me is the truth, אמת חפצת בטחות, and with Your help I can go from my misery (עצמות דכית) to joy. תשובה is possible, but only with G-d’s help, and only if we start the process:

פתחו לי פתח כחודה של מחט ואני אפתח לכם כפתחו של אולם.

And then the parallel stich is the positive: לב טהור ברא לי אלקים. The complete pasuk in (בראשית ד:ז) is לפתח חטאת רבץ; ואליך תשוקתו ואתה תמשל בו. We are not our יצר הרע. And, David adds, if I can achieve repentance and forgiveness, I will be an example to others: אלמדה פשעים דרכיך.

So save me from this “blood guilt” and I will write this very song that is the יסוד מוסד לעיקרי התשובה:

הצילני מדמים אלקים אלקי תשועתי;

תרנן לשוני צדקתך׃

יז א־דני שפתי תפתח; ופי יגיד תהלתך׃

יח כי לא תחפץ זבח ואתנה; עולה לא תרצה׃

יט זבחי אלקים רוח נשברה;

לב נשבר ונדכה אלקים לא תבזה׃

כ היטיבה ברצונך את ציון; תבנה חומות ירושלם׃

כא אז תחפץ זבחי צדק עולה וכליל;

אז יעלו על מזבחך פרים׃

We introduce our תפילות with the pasuk of א־דני שפתי תפתח because we are in the same situation as David is. He cannot offer a sacrifice in the בית המקדש because it has not been built, and due to his sins it will not be built. He accepts that. (There is a משכן in גבעון, but that’s really not the same thing. We’ve noted several times that the משכן never appears in ספר שמואל after the destruction of משכן שילה. ואכמ״ל). For us, we cannot offer a sacrifice in the בית המקדש because it has been destroyed. But both of us can offer a prayer instead:

קְחוּ עִמָּכֶם דְּבָרִים וְשׁוּבוּ אֶל ה׳ אִמְרוּ אֵלָיו כָּל תִּשָּׂא עָוֹן וְקַח טוֹב וּנְשַׁלְּמָה פָרִים שְׂפָתֵינוּ׃

And a sincere prayer is even better than a sacrifice (לא תחפץ זבח ואתנה; עולה לא תרצה), which is a pretty radical idea but it’s exactly what Samuel told Saul:

כב ויאמר שמואל החפץ לה׳ בעלות וזבחים כשמע בקול ה׳; הנה שמע מזבח טוב להקשיב מחלב אילים׃

כג כי חטאת קסם מרי ואון ותרפים הפצר; יען מאסת את דבר ה׳ וימאסך ממלך׃

And this relates to an obscure pasuk at the end of ספר שמואל:

וְאֵלֶּה דִּבְרֵי דָוִד הָאַחֲרֹנִים; נְאֻם דָּוִד בֶּן יִשַׁי וּנְאֻם הַגֶּבֶר הֻקַם עָל מְשִׁיחַ אֱלֹקֵי יַעֲקֹב וּנְעִים זְמִרוֹת יִשְׂרָאֵל׃

רבי שמואל בר נחמני א״ר יונתן: מאי דכתיב (שמואל ב כג) נאם דוד בן ישי ונאם הגבר הוקם על? נאם דוד בן ישי שהקים עולה של תשובה.

עולה של תשובה is generally understood as עֹולָהּ: ”the yoke of repentance“. David by admitting his guilt with Bat Sheva becomes the exemplar of someone who bears the burden of repentance. The Maharsha says that’s not what the gemara is talking about; there is no “yoke” of repentance. The Gemara is referring to the עֹולָה, the “burnt offering” of repentance:

זאת תורת העולה וגו׳: כך שנו רבותינו היתה עולה כולה קדושה מפני שלא היתה בא על עונות, אשם היתה באה על הגזילות, אבל העולה לא היתה באה לא על חטאת ולא על גזל אלא על הרהור הלב היא באה, וכן מי שהיה מהרהר בלבו דבר היה מביא קרבן העולה…ותדע לך שקרבן עולה לא בא אלא על הרהור הלב, מן איוב אתה למד שהיה מקריב על בניו שנא׳ (איוב א:ה) וַיְהִי כִּי הִקִּיפוּ יְמֵי הַמִּשְׁתֶּה וַיִּשְׁלַח אִיּוֹב וַיְקַדְּשֵׁם וְהִשְׁכִּים בַּבֹּקֶר וְהֶעֱלָה עֹלוֹת מִסְפַּר כֻּלָּם כִּי אָמַר אִיּוֹב אוּלַי חָטְאוּ בָנַי וּבֵרְכוּ אֱ־לֹהִים בִּלְבָבָם. הוי אתה מוצא שעל הרהור הלב התקין כפרה להם, וזהו קרבן עולה.

שהקים עולה של תשובה כו׳: יש לפרש דנקט עולה של תשובה ע״ש כי העולה באה על המחשבה והנה דוד לא חטא במעשה בת שבע כדאמרינן פרק במה בהמה דגט כריתות היה כותב לאשתו והוה גט למפרע אבל לפי העולה על המחשבה, חטא מיהת ונענש עליו…

The עולה is a tool for תשובה. It is the only קרבן that can be correctly translated as “sacrifice”. ה׳ doesn’t need it, we do, to put ourselves in the correct frame of mind to change:

כדי שיחשוב אדם בעשותו כל אלה כי חטא לאלקיו בגופו ובנפשו וראוי לו שישפך דמו וישרף גופו לולא חסד הבורא שלקח ממנו תמורה וכפר הקרבן הזה שיהא דמו תחת דמו נפש תחת נפש וראשי אברי הקרבן כנגד ראשי אבריו.

צו את אהרן ואת בניו לאמר זאת תורת העלה; הוא העלה על מוקדה על המזבח כל הלילה עד הבקר ואש המזבח תוקד בו׃

זאת תורת העולה הוא העולה על מוקדה: הוא העולה מיותר לגמרי, והסכימו המפרשים לומר שבא להודיע שכל העוסק בתורת עולה כאילו הקריב עולה ועל זה אמר זאת תורת העולה העוסק בתורת העולה הוא העולה זהו טוב כמו הקרבת העולה עצמה…

והודיע לנו הכתוב שזמן העולה כל הלילה עד הבוקר, ועוד ש”עד הבוקר“ מיותר, ללמוד דעת את העם על צד הרמז כמו שזמן העולה כל הלילה עד הבוקר כך הזמן המוכן לזה שהעוסק בתורת עולה דומה כאילו הקריב עולה הוא בזמן הגלות שנמשל ללילה כי אז צריכים ישראל לשלם פרים שפתותיהם, ועד הבוקר ולא עד בכלל כי בזמן שיעלה בוקרן של ישראל אז יעלו על מזבח ה׳ פרים ממש, כמו שנאמר (תהלים נא:יז) ה׳ שפתי וגו׳ ואימתי אני מבקש שתקבל ניב שפתי, כי לא תחפוץ זבח ואתנה (שם פסוק יח), ולשון כי מורה על הזמן ורצה לומר כי יהיה זמן שלא תחפוץ זבח ועל אותו זמן אני מבקש שתקבל ארשת שפתי במקום הקרבן כי על ידי העסק בתורת הקרבנות יבוא האדם גם כן לידי רוח נשברה זה שנאמר (שם פסוק יט) זבחי אלקים רוח נשברה לב נשבר ונדכה אלקים לא תבזה, ומדקאמר לא תבזה שמע מינה שעסק הקרבן עצמו נבחר לה׳ יותר מן העסק בתורת עולה. ומה שאמר זאת תורת העולה הוא העולה היינו דוקא כל הלילה בגלות כשאין זבח ומנחה, וזה שאמר אחר כך (שם פסוקים כ-כא) היטיבה ברצונך את ציון וגו׳ אז תחפוץ זבחי צדק אז יעלו על מזבחך פרים.

So now we can go back to the gemara that claims that David never sinned:

אמר רבי שמואל בר נחמני אמר רבי יונתן: כל האומר דוד חטא אינו אלא טועה.

There’s another gemara that has a similar message, that David wasn’t really at fault in the affair of Bat Sheva:

והיינו דא״ר יוחנן משום ר״ש בן יוחאי: לא דוד ראוי לאותו מעשה [רש״י: דבת שבע] ולא ישראל ראוין לאותו מעשה…אלא למה עשו? לומר לך, שאם חטא יחיד אומרים לו כלך אצל יחיד [רש״י: גזירת מלך היתה ליתן פתחון פה לשבים], ואם חטאו צבור אומרים… אצל צבור.

How can we say David didn’t sin, or that he only did it as a lesson for בעלי תשובה? I think we are mis-reading the gemara. In the context of תנ״ך, the David of the Bat Sheva incident is inconsistent with the David of the rest of ספר שמואל and the rest of תנ״ך. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen in the life of the historical David. But why write it as as such a major part of the literary work that we have before us? It’s for the lesson about ליתן פתחון פה לשבים. האומר דוד חטא אינו אלא טועה means that if you read this and all you can say is דוד חטא then you are אינו אלא טועה. You are missing the point. You are making Meir Sternberg’s mistake, reading a single chapter as an independent short story. There is a novel here, with an arc of character development that cannot conclude with דוד חטא.

[T]his is the wonder of teshuva. If someone fully and sincerely repents, then Hashem considers it as if the crime had never been done. Instead of יש מאין we have אין מיש. He turns the יש of the crime into an אין—a negation of an act that has already taken place. So, in this sense, teshuva was created before the formation of the world. Because teshuva returns conditions to where they were before the Creation to the status of אין. The misdeed is considered null and void.

This explains the statement of Chazal that “כל האומר דוד חטא אינו אלא טועה—Whoever says that King David sinned is mistaken”. On the surface, it seems strange for the Chachamim to have come to this conclusion. After all, the Tanach is very direct in its description of David’s actions; it does not whitewash anyone. Certainly, it is clear from the Tanach that David committed some חטא in regard to Batsheva. Why, then, is it wrong to think that David did something improper?

The answer is that David sinned, but he also did teshuva…[O]nce someone has repented wholeheartedly and has committed himself to not repeating his mistake, it is as if he has not sinned at all…

And that is how to read David and Bat Sheva.