In Through the Looking-Glass , Tweedledum and Tweedledee recite a poem:

“The time has come,” the Walrus said, “To talk of many things: Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax— Of cabbages—and kings— And why the sea is boiling hot— And whether pigs have wings.”

It’s Lewis Carroll, so it is inspired nonsense, but nonsense nonetheless. But we expect more from ספר משלי. Yet, somehow, in this book of ethics and morality, the time has come to talk of kings.

כח ברב עם הדרת מלך; ובאפס לאם מחתת רזון׃ כט ארך אפים רב תבונה; וקצר רוח מרים אולת׃ ל חיי בשרים לב מרפא; ורקב עצמות קנאה׃ לא עשק דל חרף עשהו; ומכבדו חנן אביון׃ לב ברעתו ידחה רשע; וחסה במותו צדיק׃ לג בלב נבון תנוח חכמה; ובקרב כסילים תודע׃ לד צדקה תרומם גוי; וחסד לאמים חטאת׃ לה רצון מלך לעבד משכיל; ועברתו תהיה מביש׃

This isn’t a book of politics; what does ברב עם הדרת מלך and צדקה תרומם גוי tell us about our relationship with others? Shlomo has mentioned kings before:

יב אני חכמה שכנתי ערמה; ודעת מזמות אמצא׃… טו בי מלכים ימלכו; ורזנים יחקקו צדק׃ טז בי שרים ישרו; ונדיבים כל שפטי צדק׃

But that’s talking about the importance of חכמה; it’s not really about the king. Shlomo will bring up advice to the king many times later in ספר משלי, but this is where it starts. We won’t talk of sealing wax and cabbages, as far as I can tell.

Presumably, in this Book of Metaphors, מלך is a metaphor. What is a מלך?

מלך הוא שכולם יטו שכם אחד לעבדו ויתנו לו כתר מלוכה, ובאמת המלך עצמו שוה לשאר העם באיכותם אך שכולם ימליכוהו עליהם ויקבלו עול מלכותו. ומושל הוא שמלכותו בא אליו בבחינת מושל שהוא גבור מכולם וכבש ארץ או אומה להיות תחת ממשלתו.

In Aramaic, מלך means to take advice.

מֵלַךְ, מֵילַךְ, מִלְכָא, מִילְכָא: counsel, advice.

So ברב עם הדרת מלך is the very definition of a מלך. It’s the עם working together that makes מלך meaningful. So, on Rosh Hashana, we make ה׳ a מלך simply by coming together to acknowledge Him. And the halacha takes the מלך of ברב עם הדרת מלך as a reference to ה׳: a mitzvah is better if it is done in public, with many people.

אמרו על בנה של מרתא בת בייתוס שהיה נוטל שתי יריכות של שור הגדול שלקוח באלף זוז, ומהלך עקב בצד גודל. ולא הניחוהו אחיו הכהנים לעשות כן, משום: בְּרׇב עָם הַדְרַת מֶלֶךְ.

והא קא משמע לן דבעינן שלשה כהנים משום דכתיב בְּרׇב עָם הַדְרַת מֶלֶךְ.

ואם בעת ההוא קורין אותה [מגילת אסתר] בצבור בבהכ״נ, אז אפילו יש לו ק׳ אנשים בביתו, מצוה לילך לשם משום בְּרׇב עָם הַדְרַת מֶלֶךְ. וכן מי שהיה ביתו סמוך לביהכ״נ וחלונותיו פתוחות לביהכ״נ, אפילו הכי צריך לילך לבהכ״נ לכולי עלמא משום בְּרׇב עָם.

Rav Hutner has a slightly different approach. A מלך isn’t so much a ruler, as a single representative of an entire population: המלך עצמו שוה לשאר העם. He notes that the Torah requires the מלך to be one of אחיך :

שום תשים עליך מלך אשר יבחר ה׳ אלקיך בו; מקרב אחיך תשים עליך מלך לא תוכל לתת עליך איש נכרי אשר לא אחיך הוא׃

ידועים הם דבריהם של חכמי הלשון, כי ההבדל בין מלוכה וממשלה הוא, כי ממשלה היא שלא ברצונו של מי שמושלים עליו, ומלוכה היא ברצונו של מי שמולכים עליו.

בודאי שזה נכון. אבל אין זה אלא חיצוניות הדברים. בפנימיותם של דברים, גנוזה היא ההכרה העדינה כי ה”אדם שבאדם“ אינו אלא הדעת שבו. ומכיון שהשם מלוכה לא יונח אלא על הדומה, שכן אריה נקרא מלך החיות מפני שגם הוא חיה. אבל אם האדם שליט על החיות, אינו אלא מושל ולא מלך, מפני שאין האדם מסוג הבעל חי. ואפילו אם הוא שולט על כל כוחותין של הזולת, כל שאינו שולט על כח הדע שבו, הרי אין הוא שולט על האדם שבזולת, ואינו אלא כשולט על בעלי חיים…מדת המלוכה דורשת דוקא את ההשתייכות לסוג אחד, ובדרך ממילא משתלשל מזה שאין מדת המלוכה נוהגת אלא בזמן שהמלוכה מתקיימת היא מדעתו של זה שמולכים עליו.

What makes us human is our “דעת”, our minds, and מלכות is only possible when the דעת of the subjects is ruled by the דעת of the ruler. Tyranny is not מלכות because there is no way to coerce דעת.

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

So how does that apply to משלי and ethics? The next pasuk provides a hint: ארך אפים רב תבונה; וקצר רוח מרים אולת. We talked about anger and losing ones temper earlier in the perek (פסוק יז: קצר אפים יעשה אולת) and we discussed it in Temper, Temper. Here, I think the idea of “you” losing control of “yourself” tells us that we imagine that there is a “real” “you” that has to control all the other things that go into making “you” as a whole. Your mind has a מלך. This sense of self is called “consciousness”.

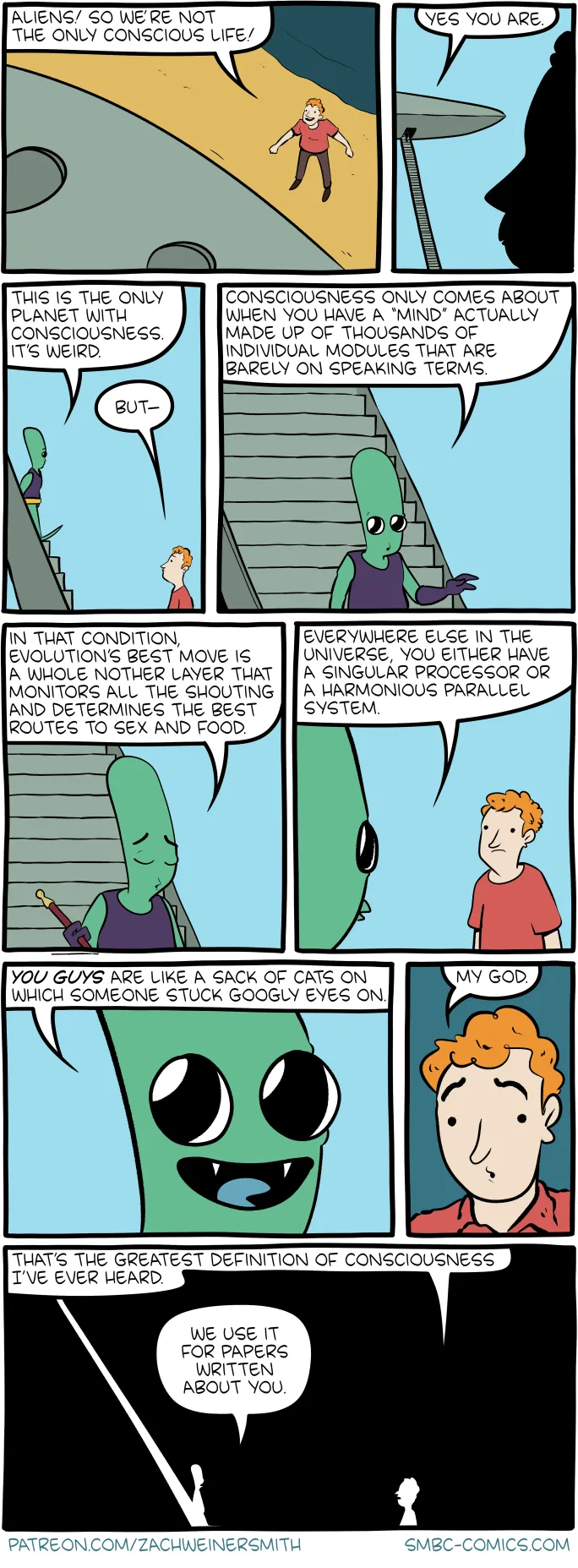

Our “mind” clearly has lots of parts: we’ve talked about לב, כליות and נפש that we translated as heart, mind and conscience. There are also all the aspects of our יצר הרע—קנאה, תאוה וכבוד—that represent our needs (like Maslow’s pyramid). But we each have a sense that there is a “me” that is overlooking and overseeing all of those. We are not just a sack of cats; those googly eyes stuck on it are who we really are.

Consciousness, in the sense used here, is the existence of an inner life: the thoughts, sensations, and feelings that constitute ‘what it is like’ to be a system acting in the world. For many, the motivation to study consciousness is encapsulated in David Chalmers’ observation that “There is nothing that we know more intimately than conscious experience, but there is nothing that is harder to explain”.

Everything we are certain of about reality and the way the universe seems to operate is described through this lens of human consciousness. If there is any objective truth which can approximate certainty, it is that something is taking place. Something is happening. Something is being experienced. It is consciousness that allows for this truth to be. This is indeed what Descartes was referring to with his famous philosophical axiom, “I think, therefore I am”…

Neuroscientists have no idea what consciousness means; philosopher David Chalmers calls it the ”hard problem“ of consciousness. But the Torah has its own approach to human consciousness.

ויברא אלקים את האדם בצלמו בצלם אלקים ברא אתו; זכר ונקבה ברא אתם׃

וייצר ה׳ אלקים את האדם עפר מן האדמה ויפח באפיו נשמת חיים; ויהי האדם לנפש חיה׃

נעשה אדם בצלמנו: הצלם האלוקי הוא הבחירה, בלי טבע מכריח, רק מרצון ושכל חפשי…אנו יודעים שהבחירה החופשית הוא מצמצום האלוקות, שהשי״ת מניח מקום לברואיו לעשות כפי מה שיבחרו.

We have an aspect of נשמת חיים that is a reflection of the divine, the צלם אלוקים that gives us a sense of our own existence and free will. It’s not something that comes automatically from being a clever ape.

David Chalmers is often credited with popularizing the concept of “philosophical zombies,” or p-zombies. The most common of the zombie-thought experiments is often used as a case against physicalism, which claims that everything in our universe, including consciousness, is physical. A p-zombie is a hypothetical creature, such as a human, which exhibits all of the outward indicators of agency; it moves, selects, adapts, and reacts but has no internally subjective or experiential qualities. The idea is, in part, to demonstrate that we can imagine a universe exactly like our own inhabited by creatures exactly like us but devoid of conscious experience. One imagines zombies driving around in cars, arguing on the street corner, and taking long walks on the beach, all the while having no conscious experience. This would be an entirely physicalist/materialist world consisting only of matter and the laws that govern matter. So if we can imagine a world exactly like ours without the need for subjective experience… why is this not the reality we have?

And, in fact, human beings can lose that צלם אלוקים. Rambam says that ה׳ may punish sins that are severe enough by turning people into p-zombies.

ואפשר שיחטא אדם חטא גדול או חטאים רבים עד שיתן הדין לפני דין האמת שיהא הפרעון מזה החוטא על חטאים אלו שעשה ברצונו ומדעתו שמונעין ממנו התשובה ואין מניחין לו רשות לשוב מרשעו כדי שימות ויאבד בחטאו שעשה…לפיכך כתוב בתורה (שמות ז:ג) וַאֲנִי [אַקְשֶׁה] אֶת לֵב פַּרְעֹה.

Being conscious gives us great moral power:

הנה מפרשת נדרים אנו רואין שהאדם יש בכחו ליצור ולחדש מצוות ועבירות חדשות, דהיינו שאם אדם נשבע שבועה שיאכל ככר זו הרי הוא מצווה לאוכלה, והרי זה מצות עשה כמו אכילת מצה, וכן כשמבטא שבועה שלא לאכול ככר זו הרי הככר אסורה כבשר חזיר ויותר, ואם הקדיש איזו דבר ובא אחר ואכלו הרי זה חייב מיתה בידי שמים, ועל כרחך מפני שהאדם באשר הוא צלם אלקים יש לו כח הזה לבדות איסורים חדשים והרי הם חלים…

And with great moral power comes great moral responsibility. In terms of the SMBC metaphor, our job is to keep all those cats under control. That is what ארך אפים רב תבונה means. תבונה, using the power of the mind, means not losing control.

מי שמושל בכעסו ואינו נוקם בעת חמתו עד שתתישב דעתו ויחשוב כדת מה לעשות מן המדה הזאת מניע להיות רב תבונה כי לא יגיע איש קצר רוח למחקר לפי שיקח בידו המחשבה הראשונה שתשפר עליו ולא ימצא את לבבו להתיישב ולהשגיח על צדי המחקר לראות אם יש צד שיסתור את מחשבתו עד שיגיע למחשבה המתקיימת, וזה לא ימצא רק בבעל הישוב ומי שהוא ארך אפים הוא בעל הישוב.

Rav Wolbe describes this as the אדם שלם, a complete human being.

האדם שהוא בדעתו השלימה ואין לבו אנסו, הוא שקוף לגמרי לעצמו ואמיתי לגמרי כלפי המציאות מבחוץ. האדם השקוף הזה—כל כחתיו נהירין לו בבת אחת, מרוממות מדרגותיו עד שפלות יצריו; גם בעמדו במצב גבוה אינו מתעלם מאי יציבותו ושהוא עלול לטעות בשכלו ולהזיק לאחרים. ודווקא דעת מקיפה זאת היא הסוללת דרך חיים שקולה, בניצול הכחות הגבוהים וזהירות מהכחות השפלים.

The next pasuk is חיי בשרים לב מרפא, what gives life to all of our בשרים, an odd phrase that has the sense of all parts of the body, is the לב מרפא, the “healing heart”. The task of the לב in this sense is to be the googly eyes, a מרפא, healer, bringing them all together for a common purpose. And רקב עצמות קנאה, your very bones will rot in the presence of קנאה, which Rashi translates not as jealousy but as anger.

ורקב עצמות קנאה: אדם בעל חמה, רקבון עצמות הוא לכל.

Again, anger makes it impossible to remain conscious in sense we are using. You just aren’t yourself when you are angry.

ריש לקיש אמר: כל אדם שכועס, אם חכם הוא—חכמתו מסתלקת ממנו.

And then Shlomo turns to religion. עשק דל חרף עשהו; ומכבדו חנן אביון. The purpose of our creation as creatures with free will and consciousness is to do good to others.

עושק דל חרף עושהו: ה׳ לא ברא את האדם לרעתו, רק לטובתו, וכל בריה שברא—הכין לה מזונה, והכין לה הכלים שבם תצוד ותכין את מזונה…אמנם, האדם, שמזונותיו קשים להשיג, ויש דלים וחלכאים שאין משיגים מזונותיהם, הכין בטבע שהאדם יעזור לחברו, כמו שנאמר (משלי כב:ב): עָשִׁיר וָרָשׁ נִפְגָּשׁוּ; עֹשֵׂה כֻלָּם ה׳.

ומי שעושק את הדל ואין נותן לו שכרו, חרף עושהו, כאילו בראו לרעתו ולא המציא לו טרפו וחיותו שבו יתקיים, וזה חרפה גדולה לעושהו, שיעשה בעל חיים ולא ימציא לו צרכיו, וכבר אמרו מאן דיהיב חיי, יהיב מזוני.

פסוק לב is harder to translate; ברעתו יִדָּחֶה רשע, in the passive “is cast off”, but the second half חסה במותו צדיק is obscure.

In his evil, a wicked one is cast off [from G-d], but he who takes shelter [in Him] remains righteous in death.

It would more parallel if we translated it as “the righteous [even] in death are sheltered [by G-d]”, the opposite of being cast aside. But I prefer the Ralbag’s reading, that this is about attitude toward adversity. The רשע is not cast off; he feels himself cast off. When faced with רעתו (translate that as “bad things that happen to him” rather than “bad things he does”), יִדָּחֶה, he feels that ה׳ has rejected him. The צדיק, on the other hand, feels sheltered, חסה, even במותו.

ברעתו ידחה רשע: הנה הרשע ידחה ברעתו כשתבא לו…והתקצף באלקיו…ואולם הצדיק לא ידחה מאמונתו אפילו בסבת המות אבל במותו יחסה בש״י.

Similarly,

ברעתו ידחה רשע: כדרך…(משלי כד:טז) כִּי שֶׁבַע יִפּוֹל צַדִּיק וָקָם וּרְשָׁעִים יִכָּשְׁלוּ בְרָעָה. שאין לו תקומה לפני רעה אחת אף כי לפני שבע, ”וחוסה במותו צדיק“, אין צריך לומר שהוא חוסה בעת הרעה שלא ידחה בה, כי גם במותו הוא חוסה בשי״ת להציל נפשו ממות.

There is the famous story about חזקיהו:

א בימים ההם חלה חזקיהו למות; ויבא אליו ישעיהו בן אמוץ הנביא ויאמר אליו כה אמר ה׳ צו לביתך כי מת אתה ולא תחיה׃ ב ויסב את פניו אל הקיר; ויתפלל אל ה׳ לאמר׃ ג אנה ה׳ זכר נא את אשר התהלכתי לפניך באמת ובלבב שלם והטוב בעיניך עשיתי; ויבך חזקיהו בכי גדול׃

ד ויהי ישעיהו לא יצא חצר התיכנה; ודבר ה׳ היה אליו לאמר׃ ה שוב ואמרת אל חזקיהו נגיד עמי כה אמר ה׳ אלקי דוד אביך שמעתי את תפלתך ראיתי את דמעתך; הנני רפא לך ביום השלישי תעלה בית ה׳׃ ו והספתי על ימיך חמש עשרה שנה ומכף מלך אשור אצילך ואת העיר הזאת; וגנותי על העיר הזאת למעני ולמען דוד עבדי׃

אמר ליה [ישעיהו לחזקיהו]: כבר נגזרה עליך גזירה. אמר ליה: בן אמוץ, כלה נבואתך וצא! כך מקובלני מבית אבי אבא, אפילו חרב חדה מונחת על צוארו של אדם, אל ימנע עצמו מן הרחמים.

And so this connects to next pasuk, בלב נבון תנוח חכמה; חכמה will be at rest in a לב נבון. As Shlomo said before, ארך אפים רב תבונה.That is the ethical message: equanimity goes with wisdom which goes with righteousness. We quote the pasuk in ברכת המזון:

נער הייתי גם זקנתי ולא ראיתי צדיק נעזב; וזרעו מבקש לחם׃

How can David claim that he has never seen a צדיק whose children were beggars? That’s clearly false. Hirsch and the Etz Yosef (Enoch Zundel ben Yoseph, 19th century commentator on מדרש תנחומא, ויצא, ג) both translate וזרעו מבקש לחם as “[even] when his children are begging.” The צדיק does not feel himself abandoned when he has to depend on others; he is aware that ה׳ provides but does so in various ways. Just as he gives graciously, he accepts graciously.

And so our pasuk says:

בלב נבון תנוח חכמה: תשכן ותשקט בנחת, לשון מנוחה ומרגוע.

And then ובקרב כסילים תודע means “in the midst of fools it [חכמה] will become known”. Rashi says that it means that the fool needs to show off whatever wisdom they have; they have to prove to others that they are smart. We’ve translated כסיל as someone who is a fool because they are self-confident; they know everything already.

ובקרב כסילים תודע: מעט חכמה שבלבו מכריזה. (בבא מציעא פה,ב) איסתרא בלגינא קיש קיש קריא.

But that, of course is missing the point of what חכמה is. The כסיל is a “Well, Actually” person.

[T]he term “Well Actually” is a slang term used to describe a particular type of person who feels the need to interject into conversations and correct others, often in a condescending or pedantic manner. These individuals typically have an over-inflated sense of their own intelligence and knowledge, and believe that they are always right and everyone else is wrong.

The “Well Actually” person can be found in all walks of life, from the workplace to social gatherings, and they often make themselves known by interrupting conversations with unsolicited corrections or fact-checking. They may also use phrases like “um, actually” or “well, technically” to preface their corrections.

חכמה is being able to integrate all aspects of your inner self, with the humility to learn from the outside world. שקוף לגמרי לעצמו ואמיתי לגמרי כלפי המציאות מבחוץ.

And then we have פסוק לד: צדקה תרומם גוי; וחסד לאמים חטאת. At the literal level this is a statement about political philosophy.

Tzedakah, righteousness, denotes justice under which all people are guaranteed certain rights and entitlements. When such a system is implemented fully and fairly, it promotes equality, and a national community. Every member of the nation is equal in both rights and obligations, and the full benefit of tzedakah is extended to everyone.

Chesed, favor or lovingkindness, can by its nature be practiced only by individuals for the benefit of individuals. For a country to do so, however, through special dispensations and grants, would constitute favoritism, and should be avoided.

An individual has privileges belonging exclusively to him and can use them according to his own private judgment, but states have no private means at their disposal. Their means and rights belong to the population collectively. Thus, the state cannot award individual grants or dispensations without doing an injustice to others. Consequently, the mercy or kindness of states is a sin, for the state cannot practice custom-tailored kindness without perpetrating a sin.

But applying it to the metaphor of the conscious self works as well. Favoring one cat in the sack leads to an imbalance that prevents good moral judgment.

The section ends with רצון מלך לעבד משכיל; ועברתו תהיה מביש which literally means:

The king favors a capable servant; He rages at an incompetent one.

But I would rather take עברתו תהיה מביש as referring to the king; “the king’s anger leads to incompetence” (I like JPS’s translation of מביש). Anger is, as we said above, the loss of control over the sack of cats. רצון only comes from keeping yourself together.

…כוונת התורה להמשיל השכל בכל תאוות הנפש ולהגבירו עליהן. ומן הידוע כי הגברת התאוה על השכל היא ראש כל חטאת וסבת כל גנות.

Ramchal uses the word להמשיל. But being a מושל on תאוות הנפש leads to קצר רוח and עברה. The goal is to be a מלך instead.

השכל־הצורה מעמיד כל כח על מקומו, משתמש בכל תאוה במקום שצריך להשתמש בה, מרחק את הדמיון המשרת את התאוות ומשתמש בו לצורך עבודת ה׳.

That is ברב עם הדרת מלך. So be a king in your own mind and you will be able to integrate all the aspects of your self. That, Shlomo says, is a prerequisite to חכמה which is a prerequisite to the sort of moral judgment that is demanded of us.

And then maybe we can talk of whether pigs have wings.