This is a re-presentation of פרשת מקץ תשע״ח, based on Rabbi David Fohrman’s lecture from the 2017 ימי עיון בתנ״ך. I think it was jaw-droppingly innovative, and I am going to present my own version of how to understand the haftorah this week (it’s not the same as Rabbi Fohrman’s; go listen to him!).

The connection between the parasha and the haftorah is in the first pasuk:

ויקץ שלמה והנה חלום; ויבוא ירושלם ויעמד לפני ארון ברית אדנ־י ויעל עלות ויעש שלמים ויעש משתה לכל עבדיו׃

ותבלענה השבלים הדקות את שבע השבלים הבריאות והמלאות; וייקץ פרעה והנה חלום׃

וייקץ והנה חלום means that it was a Dream with a capital D. And something must be done!

והנה חלום: והנה נשלם חלום שלם לפניו והוצרך לפותרים.

What was Shlomo’s dream? It’s not in the haftorah, but in the first half of the perek:

ה בגבעון נראה ה׳ אל שלמה בחלום הלילה; ויאמר אלקים שאל מה אתן לך׃

ו ויאמר שלמה אתה עשית עם עבדך דוד אבי חסד גדול כאשר הלך לפניך באמת ובצדקה ובישרת לבב עמך; ותשמר לו את החסד הגדול הזה ותתן לו בן ישב על כסאו כיום הזה׃

ז ועתה ה׳ אלקי אתה המלכת את עבדך תחת דוד אבי; ואנכי נער קטן לא אדע צאת ובא׃

ח ועבדך בתוך עמך אשר בחרת; עם רב אשר לא ימנה ולא יספר מרב׃

ט ונתת לעבדך לב שמע לשפט את עמך להבין בין טוב לרע; כי מי יוכל לשפט את עמך הכבד הזה׃

י וייטב הדבר בעיני א־דני; כי שאל שלמה את הדבר הזה׃

יא ויאמר אלקים אליו יען אשר שאלת את הדבר הזה ולא שאלת לך ימים רבים ולא שאלת לך עשר ולא שאלת נפש איביך; ושאלת לך הבין לשמע משפט׃

יב הנה עשיתי כדבריך; הנה נתתי לך לב חכם ונבון אשר כמוך לא היה לפניך ואחריך לא יקום כמוך׃

יג וגם אשר לא שאלת נתתי לך גם עשר גם כבוד; אשר לא היה כמוך איש במלכים כל ימיך׃

יד ואם תלך בדרכי לשמר חקי ומצותי כאשר הלך דויד אביך והארכתי את ימיך׃

So what does Shlomo do with his dream? It’s more that something is done to him. ה׳ sets up a situation where he can demonstrate his wisdom:

טז אז תבאנה שתים נשים זנות אל המלך; ותעמדנה לפניו׃…כג ויאמר המלך זאת אמרת זה בני החי ובנך המת; וזאת אמרת לא כי בנך המת ובני החי׃

כד ויאמר המלך קחו לי חרב; ויבאו החרב לפני המלך׃

כה ויאמר המלך גזרו את הילד החי לשנים; ותנו את החצי לאחת ואת החצי לאחת׃

כו ותאמר האשה אשר בנה החי אל המלך כי נכמרו רחמיה על בנה ותאמר בי אדני תנו לה את הילוד החי והמת אל תמיתהו; וזאת אמרת גם לי גם לך לא יהיה גזרו׃

כז ויען המלך ויאמר תנו לה את הילוד החי והמת לא תמיתהו; היא אמו׃

כח וישמעו כל ישראל את המשפט אשר שפט המלך ויראו מפני המלך; כי ראו כי חכמת אלקים בקרבו לעשות משפט׃

The wisdom here is understanding human nature, לב שמע לשפט את עמך.

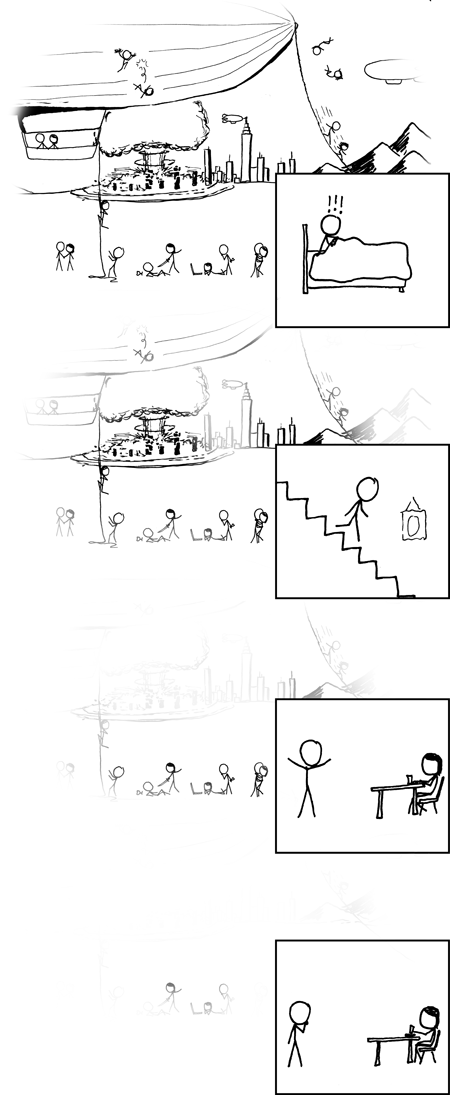

But Rabbi Fohrman is bothered by this story. It’s too pat, to simple, to say that with one clever decision, Shlomo proves to the people how wise he is. So he proposes that the story of the two babies was in fact part of the dream. Just like in our parasha, Pharaoh had a dream, woke, then had another dream, so too here. Shlomo had a dream of his coversation with הקב״ה, woke, then dreamed again of the two babies. ה׳ is teaching Shlomo something with this vision of the two זונות.

Now I disagree with that part: ויקץ שלמה והנה חלום is clearly parallel to וייקץ פרעה והנה חלום, which is after Pharaoh’s second dream. והנה חלום means that the dreaming has ended; as Rashi says, נשלם חלום שלם לפניו והוצרך לפותרים. So I would read the story of the two babies as something that actually happened, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t set up by ה׳ to teach Shlomo a lesson.

Who was Shlomo? It goes back to David and Bat Sheva:

יג ויאמר דוד אל נתן חטאתי לה׳;

ויאמר נתן אל דוד גם ה׳ העביר חטאתך לא תמות׃

יד אפס כי נאץ נאצת את איבי ה׳ בדבר הזה; גם הבן הילוד לך מות ימות׃

טו וילך נתן אל ביתו; ויגף ה׳ את הילד אשר ילדה אשת אוריה לדוד ויאנש׃

טז ויבקש דוד את האלקים בעד הנער; ויצם דוד צום ובא ולן ושכב ארצה׃

…יח ויהי ביום השביעי וימת הילד; ויראו עבדי דוד להגיד לו כי מת הילד כי אמרו הנה בהיות הילד חי דברנו אליו ולא שמע בקולנו ואיך נאמר אליו מת הילד ועשה רעה׃

יט וירא דוד כי עבדיו מתלחשים ויבן דוד כי מת הילד; ויאמר דוד אל עבדיו המת הילד ויאמרו מת׃

…כד וינחם דוד את בת שבע אשתו ויבא אליה וישכב עמה; ותלד בן ויקרא (ותקרא) את שמו שלמה וה׳ אהבו׃

כה וישלח ביד נתן הנביא ויקרא את שמו ידידיה בעבור ה׳׃

Rabbi Fohrman notices the parallels to the נשים זנות story: there are two infants, one alive, one dead. There are two parents who are in conflict, David and Uriah. And Uriah’s role here needs some background.

We can’t read the story of David and Bat Sheva without thinking of the Biblical precedents in David’s own ancestry: the story of Yehudah and Tamar, and the story of Boaz and Ruth. Both involve a childless widow who is “redeemed”—with the concept of יבום, if not the technical mitzvah of יבום—by an ancestor of David, a proto-מלך ישראל. And both only happen when the woman takes the initiative to push the man to do the right thing. Why is יבום so important in the history of מלכות ישראל?

ה כי ישבו אחים יחדו ומת אחד מהם ובן אין לו לא תהיה אשת המת החוצה לאיש זר; יבמה יבא עליה ולקחה לו לאשה ויבמה׃

ו והיה הבכור אשר תלד יקום על שם אחיו המת; ולא ימחה שמו מישראל׃

We’ve talked before that יקום על שם אחיו doesn’t mean that the child is literally named after the late brother; it means that the child is the spiritual legacy of the deceased. It means that the child is raised as the son of the late brother; the biological father is in essence giving up his fatherhood, to grant it to his brother who never fathered children. Is is a form of the ultimate kindness, חסד של אמת. That is enough to make it important for a מלך ישראל, but there is more to it.

We have understood that David’s saw the exposure of Bat Sheva as a sign from ה׳ that she was his בּאַשערט, that this story was the same as the story of Yehudah and Tamar. We (as the readers, with the previous story in mind) and David (as the one living these stories) know what to expect: Uriah is one of David’s גבורים, off fighting an interminable war. David just has to wait, and he will get the news that Uriah has died in battle. He will then marry Bat Sheva as an act of יבום, an act of selfless חסד, demonstrating that he is fit to be מלך ישראל. But he fails.

תנא דבי רבי ישמעאל: ראויה היתה לדוד בת שבע בת אליעם אלא שאכלה פגה.

- פַּגָּה

- unripe fruit

- פַּג

- preemie, premature baby

שאכלה פגה: שקפץ את השעה ליזקק ע״י עבירה.

So, both from a literary/historical perspective, and from the perspective of David’s own תשובה, David has to do יבום with Bat Sheva. The child is to be, in effect, Uriah’s. In this model, Shlomo is being metaphorically told that this very case came before הקב״ה: two parents with a claim to an infant. How should Bat Sheva’s child be divided?

What I’m going to say is a little different from the way Rabbi Fohrman presented it, but I think it represents an interesting way to look at the text.

When David prays for Bat Sheva’s baby, ויבקש דוד את האלקים בעד הנער, what is he praying for? He needs this baby. When he tries to build the בית המקדש (10 years before the story of Bat Sheva), he is told:

ד ויהי בלילה ההוא;

ויהי דבר ה׳ אל נתן לאמר׃

ה לך ואמרת אל עבדי אל דוד

כה אמר ה׳; האתה תבנה לי בית לשבתי׃

ו כי לא ישבתי בבית למיום העלתי את בני ישראל ממצרים ועד היום הזה; ואהיה מתהלך באהל ובמשכן׃

…

יב כי ימלאו ימיך ושכבת את אבתיך והקימתי את זרעך אחריך אשר יצא ממעיך; והכינתי את ממלכתו׃

יג הוא יבנה בית לשמי; וכננתי את כסא ממלכתו עד עולם׃

יד אני אהיה לו לאב והוא יהיה לי לבן אשר בהעותו והכחתיו בשבט אנשים ובנגעי בני אדם׃

The key phrase there is אשר יצא ממעיך, in the future. Not only will David not build the בית המקדש, but none of the children he has now will build it. It will be a son who will be born who will build the בית המקדש. And until Bat Sheva, he has no other children. This child that bat Sheva is carrying represents his hope of a legacy, of a future. He can’t give it up. But after the sin of Uriah and Bat Sheva, נתן told him (שמואל ב יב:י) ועתה לא תסור חרב מביתך עד עולם. This, Rabbi Forhman says, is the meaning of (מלכים א ג:כד) ויאמר המלך קחו לי חרב. Both Uriah and David have a spiritual claim to the child. ה׳ says, OK, split him in half. But no child can survive that. The newborn infant dies.

Rabbi Fohrman understands that in the case of the next child, Shlomo, David realizes that he cannot be the father. This is actually hinted in the text. The first child’s birth is described as (שמואל ב יא:כז) ותלד לו בן. Shlomo’s birth is described as (שמואל ב יב:כד) ותלד בן. This child is not לו, his. He is willing to let the יבום stand and remove this son from his legacy.

Then ה׳ says, now this child can be your legacy. But remember that he is not really yours; he is Mine: אני אהיה לו לאב והוא יהיה לי לבן. And so ה׳ gives him an additional name: וה׳ אהבו…ויקרא את שמו ידידיה בעבור ה׳.

With the incident of the two זנות, ה׳ gives Shlomo a glimpse of his own past and his own destiny. And he needs to know the importance of יבום, of saying בי אדני תנו לה את הילוד החי והמת אל תמיתהו, of giving up a child for the greater good. For there is a terrible danger in מלכות: it is inherited. A peaceful, lawful succession requires a dynasty (they hadn’t yet invented elections):

יד כי תבא אל הארץ אשר ה׳ אלקיך נתן לך וירשתה וישבתה בה; ואמרת אשימה עלי מלך ככל הגוים אשר סביבתי׃

טו שום תשים עליך מלך אשר יבחר ה׳ אלהיך בו; מקרב אחיך תשים עליך מלך לא תוכל לתת עליך איש נכרי אשר לא אחיך הוא׃

…

כ לבלתי רום לבבו מאחיו ולבלתי סור מן המצוה ימין ושמאול למען יאריך ימים על ממלכתו הוא ובניו בקרב ישראל׃

הוא ובניו: מגיד שאם בנו הגון למלכות, הוא קודם לכל אדם.

But the fact that this authority is inherited does not mean it belongs to the king, the way personal property does. The successor inherits power that is granted by ה׳ to the עם as a whole: שום תשים עליך מלך.

ולאו כל דבעי מלכא מורית מלכותא לבניה? אמר רב פפא, אמר קרא: הוא ובניו בקרב ישראל, בזמן ששלום בישראל קרינא ביה הוא ובניו, ואפילו בלא משיחה.

וכשיש מחלוקת פסקה הירושה. שכן כתיב ”הוא ובניו בקרב ישראל“, שירצה כאשר יהיה בקרב ישראל ובהסכמת כולם, אז הוא מוריש את בניו ולא בעי משיחה. אבל יש מחלוקת, לאו ירושה וממנו מתחיל וצריך משיחה.

If the king sees his successor as his own son, then the dynasty exists for the sake of perpetuating the dynasty, not for the sake of the kingdom.

Pournelle’s Iron Law of Bureaucracy states that in any bureaucratic organization there will be two kinds of people: those who work to further the actual goals of the organization, and those who work for the organization itself…The Iron Law states that in all cases, the second type of person will always gain control of the organization, and will always write the rules under which the organization functions.

The simplest way to explain the behavior of any bureaucratic organization is to assume that it is controlled by a cabal of the enemies of the stated purpose of that bureaucracy.

The case of the two זונות and their two infants served as a tangible reminder to Shlomo of Who he really worked for.